Key findings from a study on non-use of childcare among families in Canada

Topic: Children and youth

Jennifer Zwicker

Jennifer Zwicker is Director of Social Policy and Health at the School of Public Policy, associate professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Calgary, Canada Research Chair (II) in Disability Policy for Children and Youth, and Chief Scientist for Kids Brain Health Network. Her research program assesses interventions and informs policy around allocation of funding, services, and supports for youth with disabilities and their families. Strong stakeholder and government collaboration has been critical in the translation of peer-reviewed publications to policy papers, op-eds and briefing notes for provincial and federal ministries and senate committees. Her work recently informed the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences National Autism Strategy Working Group and Royal Society of Canada Expert Working Group to develop disability inclusive policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. She has been recognized for her policy leadership as an Action Canada Alumni, Governor General Leadership Forum, and Canada’s Top 40 Under 40.

Annie Pullen Sansfaçon

Annie Pullen Sansfaçon holds a PhD in Ethics and Social Work (De Montfort University, UK, 2007) and has been focused on anti-oppressive approaches and ethics since the beginning of her career. Building on these themes, she developed a research focus aimed at better understanding the experiences of oppression and resistance among gender-diverse youth, such as transgender and non-binary youth, Two-Spirit youth, and youth who detransition, as well as the development of best practices to support them. She is also interested in parental and social support and its impact on these different groups of young people. The research projects she leads, both nationally and internationally, have been published in numerous scholarly articles and five books on the subject. She co-founded and currently co-directs CRI-JaDE (Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur la justice intersectionnelle, la décolonisation et l’équité; Centre for Research on Intersectional Justice, Decolonization, and Equity), and is an affiliated researcher with the School of Social Work at Stellenbosch University in South Africa.

Simona Bignami

Simona Bignami is a demographer specializing in quantitative methods and family dynamics. Broadly speaking, she is interested in the relationship between social influence, family dynamics, and demographic outcomes and behaviours, and the extent to which empirical evidence helps us understand this relationship. Her most recent work focuses on migrants’ and ethnic minorities’ family dynamics, attempting to improve their measurement with innovative data and methods, and to understand their role for demographic and health outcomes. Her research on these topics takes a comparative perspective, and spans from developing to developed country settings. Although her research is quantitative, she has experience collecting household survey data and conducting qualitative interviews and focus groups in different settings.

Robin McMillan

Robin McMillan has spent her career of over 30 years working in the early learning sector. For the first eight years, she worked as an Early Childhood Educator with preschool children. She left the front line to develop resources for practitioners at the Canadian Child Care Federation (CCCF). She has been with the CCCF since 1999 and worked her way from Project Assistant to Project Manager to her present role as Innovator of Projects, Programs and Partnerships. Highlights of her career with CCCF have been managing over 20 national and international projects, including a CIDA project in Argentina and presenting a paper with the Honourable Senator Landon Pearson to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva, Switzerland.

Robin served as a board member on the Ottawa Carleton Ultimate Association for two years, as well as participated in organizing numerous local charity events. She founded and facilitated a local parent support group, Ottawa Parents of Children with Apraxia, and a national group, Apraxia Kids Canada. She is married and has a 17-year-old son with a severe speech disorder, childhood apraxia of speech, and a mild intellectual disability, which launched her into the world of parent advocacy. She was the recipient of the Advocate of the Year Award in 2010 from the Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America.

About the Organization: We are the community in the early learning and child care sector in Canada. Professionals and practitioners from coast to coast to coast belong in our community. We give voice to the deep passion, experience, and practice of Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) in Canada. We give space to excellent research in policy and practice to better inform service development and delivery. We provide leadership on issues that impact our sector because we know we are making a difference in the lives of young children—our true purpose, why we exist—to make a difference in these lives. What gets talked about, explored, and shared in our community is always life changing, and we know that. We are a committed, passionate force for positive change where it matters most—with children.

Gaëlle Simard-Duplain

Gaëlle Simard-Duplain is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Carleton University. Her research focuses on the determination of health and labour market outcomes. She is particularly interested in the interaction of policy and family in mitigating or exacerbating inequalities, through both intrahousehold family dynamics and intergenerational transmission mechanisms. Her work predominantly uses administrative data sources, sometimes linked to survey data, and quasi-experimental research methods. Gaëlle holds a PhD in Economics from the University of British Columbia.

Andrea Doucet

Andrea Doucet is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Gender, Work, and Care, Professor in Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University, and Adjunct Professor at Carleton University and the University of Victoria (Canada). She has published widely on care/work policies, parental leave policies, fathering and care, and gender divisions and relations of paid and unpaid work. She is the author of two editions of the award-winning book Do Men Mother? (University of Toronto Press, 2006, 2018), co-author of two editions of Gender Relations: Intersectionality and Social Change (Oxford, 2008, 2017), and co-editor of Thinking Ecologically, Thinking Responsibly: The Legacies of Lorraine Code (SUNY, 2021). She is currently writing about social-ecological care and connections between parental leaves, care leaves, and Universal Basic Services. Her recent research collaborations include projects with Canadian community organizations on young Black motherhood (with Sadie Goddard-Durant); feminist, ecological, and Indigenous approaches to care ethics and care work (with Eva Jewell and Vanessa Watts); and social inclusion/exclusion in parental leave policies (with Sophie Mathieu and Lindsey McKay). She is the Project Director and Principal Investigator of the Canadian SSHRC Partnership program, Reimagining Care/Work Policies, and Co-Coordinator of the International Network of Leave Policies and Research.

Liv Mendelsohn

Liv Mendelsohn, MA, MEd, is the Executive Director of the Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence, where she leads innovation, research, policy, and program initiatives to support Canada’s caregivers and care providers. A visionary leader with more than 15 years of experience in the non-profit sector, Liv has a been a lifelong caregiver and has lived experience of disability. Her experiences as a member of the “sandwich generation” fuel her passion to build a caregiver movement in Canada to change the way that caregiving is seen, valued, and supported.

Over the course of her career, Liv has founded and helmed several organizations in the disability and caregiving space, including the Wagner Green Centre for Accessibility and Inclusion and the ReelAbilities Toronto Film Festival. Liv serves as the chair of the City of Toronto Accessibility Advisory Committee. She has received the City of Toronto Equity Award, and has been recognized by University College, University of Toronto, Empowered Kids Ontario, and the Jewish Community Centres of North America for her leadership. Liv is a senior fellow at Massey College and a graduate of the Mandel Institute for Non-Profit Leadership and the Civic Action Leadership Foundation DiverseCity Fellows program.

About the Organization: The Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence supports and empowers caregivers and care providers, advances the knowledge and capacity of the caregiving field, and advocates for effective and visionary social policy, with a disability-informed approach. Our expertise and insight, drawn from the lived experiences of caregivers and care providers, help us campaign for better systems and lasting change. We are more than just a funder; we work closely with our partners and grantees towards shared goals.

Deborah Norris

Holding graduate degrees in Family Science, Deborah Norris is a professor in the Department of Family Studies and Gerontology at Mount Saint Vincent University. An abiding interest in the interdependence between work and family life led to Deborah’s early involvement in developing family life education programs at the Military Family Resource Centre (MFRC) located at the Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Halifax. Insights gained through conversation with program participants were the sparks that ignited a long-standing commitment to learning more about the lives of military-connected family members—her research focus over the course of her career to date. Informed by ecological theory and critical theory, Deborah’s research program is applied, collaborative, and interdisciplinary. She has facilitated studies focusing on resilience(y) in military and veteran families; work-life balance in military families; the bi-directional relationship between operational stress injuries and the mental health and wellbeing of veteran families; family psychoeducation programs for military and veteran families; and the military to civilian transition. She has collaborated with fellow academic researchers, Department of National Defense (DND) scientists, Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) personnel, and others. Recently, her research program has expanded to include an emphasis on the impacts of operational stress on the families of public safety personnel.

Susan Prentice

Susan Prentice holds the Duff Roblin Professor of Government at the University of Manitoba, where she is a professor of Sociology. She specializes in family policy broadly, and child care policy specifically. She has written widely on family and child care policy, and a list of her recent publications can be found at her UM page. At the undergraduate and graduate level, she teaches family policy courses. Susan works closely with provincial and national child care advocacy groups, and is a member of the Steering Committee of the Childcare Coalition of Manitoba.

Shelley Clark

Shelley Clark, James McGill Professor of Sociology, is a demographer whose research focuses on gender, health, family dynamics, and life course transitions. After receiving her PhD from Princeton University in 1999, Shelley served as program associate at the Population Council in New York (1999–2002) and as an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago (2002–2006). In the summer of 2006, she joined the Department of Sociology at McGill, where in 2012 she became the founding Director of the Centre on Population Dynamics. Much of her research over two decades has examined how adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa make key transitions to adulthood amid an ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Additional work has highlighted the social, economic, and health vulnerabilities of single mothers and their children in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently she has embarked on a new research agenda to assess rural and urban inequalities and family dynamics in the United States and Canada. Her findings highlight the diversity of family structures in rural areas and the implications of limited access to contraception on rural women’s fertility and reproductive health.

Isabel Côté

Isabel Côté is a full professor in the department of social work at Université du Québec en Outaouais. She holds the Canada Research Chair on Third-Party Reproduction and Family Ties, is a member of Partenariat Famille en mouvance (a research partnership on the changing family) and of the Réseau québécois en études féministes (RéQEF) (a Quebec network for feminist studies). Her research program aims to develop a global understanding of third-party reproduction that brings together the viewpoints of all parties, including parents, donors, surrogates, the children conceived this way, and the extended families. Using innovative qualitative methodologies, her work draws on the theoretical contributions of sociology of the family, kinship anthropology, and feminist and LGBTQ studies, and takes a fresh look at contemporary family realities. In an innovative way, her work considers children as full agents in the construction of knowledge about families created thanks to third-party reproduction. Lastly, the results of her work provide material, based on empirical data, to inform the social debate about the issues raised by third-party reproduction while also suggesting courses of action to better support the wellbeing of the people concerned.

Denise Whitehead

Denise Whitehead is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Sexuality, Marriage, and Family Studies, and cross-appointed in Sociology and Legal Studies, at St. Jerome’s University, in the University of Waterloo. Denise is a trained lawyer (Osgoode Hall, Bar of Ontario) and social scientist (PhD, Family Relations and Human Development, University of Guelph). Denise conducts socio-legal research on practice and policy issues related to separation and divorce that affect all members of the family system. Denise’s teaching covers a wide breadth of topics including parents and children; relationship formation and dissolution; family law; family policy; conflict in close relationships; and caregiving.

Research Snapshot: Children in Out-of-Home Care in Canada: Insights from Administrative Data

Highlights from a study about the number of children in out-of-home care in Canada

Research Snapshot: Families with Refugee Backgrounds Rebuilding New Lives in Saskatchewan

Highlights of a study on what contributed to refugees’ resilience after resettling in Regina, Saskatchewan

Research Snapshot: Children’s Digital Play as Collective Family Resilience in the Face of the Pandemic

Highlights of a study of how digital play helped foster children’s agency, creativity, and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

Research Snapshot: Peer and Family Belongingness Impact on the Mental Health of Black LGBTQ+ Youth

Highlights from a study about family support and Black LGBTQ+ youth

Research Snapshot: Inuit Mothers’ Visions for Child and Family Wellness in Nunavut, Canada

Summary of a study on how the child welfare system is perceived by Inuit mothers

Research Snapshot: Family Experiences and Anti-Black Racism in Early Childhood Education

Summary of a study on how anti-Black racism affects Black Canadians in early childhood

Research Snapshot: Motivations and Challenges for Grandparent–Grandchild Outdoor Play in Early Childhood

Summary of a study on the perspectives of grandparents regarding outdoor play with their young grandchildren.

Knowledge Snapshot: Perspectives of Indigenous Families on Early Learning and Childcare in Urban Settings

Summary of a study on Indigenous families’ thoughts on early learning and childcare in urban settings

Research Snapshot: “Family Stories” and Intergenerational Voices of Adoption

A summary of a study on the effects of adoption in adulthood

Research Snapshot: Maternal Labour Force Participation and Separation Anxiety Among Children

Findings from a study about working mothers and separation anxiety among children

Research Snapshot: Protecting Against Food Insecurity: Impacts on Mental Health and Wellbeing

Summary of a study on protecting children from food insecurity

Research Snapshot: Parents, Homeschooling, and Relationship Conflict During COVID-19

Highlights from a study on how providing homeschooling during COVID affected parents

Father’s Day 2023: Changing Roles, Changing Profiles

A roundup of stats about dads in Canada in advance of Father’s Day 2023

Research Snapshot: Family Victimization of Sexual and Gender Minority Youth in Canada

Highlights from a study about LGBTQ2S+ youth victimized by family

Research Snapshot: Examining Benefits and Barriers to Participating in Family Physical Activity

Highlights from a study about families and active leisure

Research Snapshot: Parenthood and the Gendered Impact of Job Loss

Highlights from a study about gendered consequences of job loss

Research Snapshot: Young People Negotiating Transnational Family Relationships

Findings from a study on relationships in migrant families after reunification

Policy Brief: Access to Parental Benefits in Canada

A 50-year review of access to parental benefits in Canada

VIDEO: Sophie Mathieu on Childcare in Quebec

A new video from Reimagining Care/Work describes childcare in Quebec

Research Snapshot: Parent–Child Separations Among First Nations and Métis Families

A summary of a recent study on the impact of parent–child separations on First Nations families

From Toddlers to Teens – Examining Mobile Work and Its Impact on Family Evolution: Amber’s Story (Families, Mobility, and Work)

Summary of a chapter on the impacts of work-related mobility on family relationships

November 8, 2022

The chapter “From Toddlers to Teens – Examining Mobile Work and Its Impact on Family Evolution: Amber’s Story” is based on a life narrative distilled from multiple conversational interviews with a woman living in rural PEI. Her story describes the evolution of her personal and family life during 12 years of her husband’s out-of-province rotational work and as her children grew from “tots to teens.” The chapter talks about entry into rotational work, its prolongation and challenges, and the strategies the family developed to overcome those challenges.

This chapter is one of many rich contributions included in Families, Mobility, and Work, a compilation of articles and other knowledge products based on research from the On the Move Partnership. Published in September 2022 by Memorial University Press, this book is now available in print, as an eBook, and as a free-open access volume available in full on the Memorial University website.

“Amber’s narrative provides key insights into the experiences and reflections of women as they adjust and adapt to their diverse roles as parents and partners as these are repeatedly negotiated and dependent on whether a loved one is coming or going for mobile work. These insights relate to time, place, and relationship, and show that Eddie’s participation in mobile work shaped all aspects of Amber’s life as a parent and partner, as well as the evolution of their family lives.” – Christina Murray, PhD, Hannah Skelding, and Sylvia Barton, PhD

Access Families, Mobility, and Work

Chapter abstract

Central to this chapter is a narrative representation of six conversational interviews conducted over seven weeks with one individual, Amber, as part of author Christina Murray’s doctoral research in rural Prince Edward Island. That research consisted of similar interviews with four women whose husbands had been working in other provinces over a period of several years. The contribution opens with a brief description of the research objectives and methods that informed the larger research. This is followed by “Amber’s Story,” where one of the study participants reflects on the evolution of her marriage and family over the 12 years during which her husband, Eddie, had been travelling for work from rural PEI to northern Alberta. He originally left when their children were two and four and was only gone in the winter. Shortly after that, he began working away year-round. At the time of the conversations, the children were 14 and 17 and the son had just spent his first summer working in Alberta with his dad. The story provides an understanding of how labour migration came to permeate Amber’s personal and family life. It touches on pivotal research themes such as specific roles and responsibilities, family evolution and transitions, communication and belonging, and marriage and community relations. The contribution concludes with some recommendations arising from the doctoral research for better support for women and families who have loved ones travelling long distances for employment and information on programming implemented in direct response to these recommendations.

Central to this chapter is a narrative representation of six conversational interviews conducted over seven weeks with one individual, Amber, as part of author Christina Murray’s doctoral research in rural Prince Edward Island. That research consisted of similar interviews with four women whose husbands had been working in other provinces over a period of several years. The contribution opens with a brief description of the research objectives and methods that informed the larger research. This is followed by “Amber’s Story,” where one of the study participants reflects on the evolution of her marriage and family over the 12 years during which her husband, Eddie, had been travelling for work from rural PEI to northern Alberta. He originally left when their children were two and four and was only gone in the winter. Shortly after that, he began working away year-round. At the time of the conversations, the children were 14 and 17 and the son had just spent his first summer working in Alberta with his dad. The story provides an understanding of how labour migration came to permeate Amber’s personal and family life. It touches on pivotal research themes such as specific roles and responsibilities, family evolution and transitions, communication and belonging, and marriage and community relations. The contribution concludes with some recommendations arising from the doctoral research for better support for women and families who have loved ones travelling long distances for employment and information on programming implemented in direct response to these recommendations.

About the authors

Christina Murray, BA, RN, PhD, is an Associate Professor with the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Prince Edward Island. Her nursing practice has been grounded in public health and community development. Since 2015, Dr. Murray has been leading a program of interdisciplinary, collaborative narrative research focusing on labour migration and its impact on the health of individuals, families, and communities. She was the principal investigator on the Tale of Two Islands study and the Families, Work and Mobility community outreach project and is currently leading a project focused on grandparents raising their grandchildren on PEI. Dr. Murray is also the recipient of the Vanier Institute’s 2018 Mirabelli-Glossop Award.

Hannah Skelding is passionate about exploring the relationships between social, economic, and environmental systems. Hannah attended McMaster University, where she graduated with a Combined Honours in Arts & Science and Environmental Science. She went on to complete her Master’s in Global Affairs through the University of Prince Edward Island and the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. During her time at UPEI Hannah met Dr. Christina Murray and was exposed to the implications of interprovincial labour mobility. Hannah is currently at the University of Alberta in the Department of Resource Extraction and Environmental Sociology.

Sylvia Barton, PhD, is Professor and Chair of the School of Nursing at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, British Columbia. Throughout her career, she has integrated professional practice, research, teaching, and leadership. Since coming to academia, the focus of this integration has been in three areas: researching health-specific stories and life narratives of human experience, particularly with Indigenous populations; developing innovative change in priority areas of health; and implementing inter-professional clinical teaching and learning models. As a result of her aspirations and goal-oriented stance, she has sought to exhibit excellence through partnership, relevancy, and inspiration.

Grandparents Supporting Families Affected by Mobile Labour (Families, Mobility, and Work)

Summary of a chapter on labour mobility and intergenerational relationships.

October 25, 2022

In Families, Mobility, and Work – a collection recently published by Memorial University Press that explores the intersection between family lives and work-related mobility – researchers Dr. Christina Murray, BA, RN, PhD; Dr. Doug Lionais, PhD; and Maddie Gallant, BScN, RN, share insights on intergenerational family experiences of labour migration in Atlantic Canada.

Their chapter, “‘Above Everything Else I Just Want to Be a Real Grandparent’: Examining the Experiences of Grandparents Supporting Families Impacted by Mobile Labour in Atlantic Canada,” highlights qualitative research findings on the challenges and opportunities experienced by grandparents who have stepped up to support their younger generations when one or both parents travel long distances and/or are separated from family for work.

This chapter is one of many rich contributions included in Families, Mobility, and Work – a compilation of articles and other knowledge products based on research from the On the Move Partnership. Published in September 2022 by Memorial University Press, this book is now available in print, as an eBook, and as a free open-access volume available in full on Memorial University website.

“All participating grandparents identified challenges related to three overarching themes: increased roles and responsibilities; a struggle between their idealized/anticipated vision of grandparenting and life after retirement and their lived reality; and challenges related to negotiating their relationships with other extended family members.” – Christina Murray, Doug Lionais, and Maddie Gallant

Access Families, Mobility, and Work

Until recently, research on interprovincial labour migration in Canada has paid limited attention to the experiences of the family members left behind. The Tale of Two Islands project was a multi-year narrative study that examined how long-distance commuting for work between Cape Breton Island and Prince Edward Island (PEI) and western Canada impacted intergenerational family members, including workers and their spouses and grandparents. As part of this study, conversational interviews were carried out with individual members of ten intergenerational families in PEI and Cape Breton including with thirteen grandparents. Three focus groups including one with grandmothers (N12) and another with grandfathers (N5) were carried out in PEI. This chapter explores the challenges and opportunities experienced by grandparents impacted by long-distance, interprovincial labour migration and their reflections on how this affects their daily lives. Key themes emerging from the interviews and focus groups involving grandparents included the multiple roles and responsibilities grandparents assume as they strive to support their adult children and grandchildren impacted by labour migration; the contrast between their ideal of grandparenting and their lived reality; and the familial and financial pressures they experience. Focus groups included multiple grandparents who have ended up caring for their grandchildren full-time due to parental mental health and addiction problems often linked to mobile work. Their challenges are highlighted, along with recommended steps to help address these challenges.

About the authors

Christina Murray, BA, RN, PhD, is an Associate Professor with the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Prince Edward Island. Her nursing practice has been grounded in public health and community development. Since 2015, Dr. Murray has been leading a program of interdisciplinary, collaborative narrative research focusing on labour migration and its impact on the health of individuals, families, and communities. She was the principal investigator on the Tale of Two Islands study and the Families, Work and Mobility community outreach project and is currently leading a project focused on grandparents raising their grandchildren on PEI. Dr. Murray is also the recipient of the Vanier Institute’s 2018 Mirabelli-Glossop Award.

Doug Lionais, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Shannon School of Business at Cape Breton University, where he teaches within the MBA in Community Economic Development (CED) program. He received his PhD in Economic Geography from Durham University (UK) after earning a BBA from Cape Breton University. Dr. Lionais’ research focuses on understanding processes of uneven development and the production of depleted communities, local and regional economic development, and forms of alternative economic practice that respond to depletion.

Maddie Gallant, BScN, RN, is a practising obstetrical registered nurse and a passionate advocate for evidenced-based practice and improving patient experiences and outcomes in all areas of health care. Maddie Gallant has played a role in the Tale of Two Islands research study as a research assistant for the duration of the study. She continues to delve into the data uncovered by the study in order to disseminate and translate important findings to other healthcare professionals in the hope of improving patient care for families experiencing labour migration.

National Grandparents’ Day: New Insights from Canadian Research

A roundup of new insights and research on grandparents in Canada.

Research Snapshot: Overrepresentation of Black Children in Ontario’s Child Welfare System

Highlights from a study exploring child welfare workers’ thoughts on the overrepresentation of Black children in child welfare

Research Snapshot: Child Welfare, Race, and Family Reunification in Quebec

Findings from a study on the impacts of race on family reunification.

Research Snapshot: Impact of Maternal Incarceration on Family Relationships

Findings from a recent study of the effects of incarceration on mothers and their children.

Census 2021: Generations and Population Aging in Canada

2021 Census releases from Statistics Canada provide a generational lens on population aging.

Research Recap: Caring for Youth from Military Families

Gaby Novoa highlights new research on “military literacy” among pediatricians.

Timeline: 50 Years of Families in Canada (1971‑2021)

Learn about how families and family experiences in Canada have changed over the past 50 years with our new timeline!

REVIEW: Mothers, Mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from a Pandemic

Alex Foster-Petrocco reviews a new book exploring the experiences of mothers during COVID-19.

Report: COVID-19 and Parenting in Canada

September 3, 2020

In June 2020, the Vanier Institute prepared the report Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada for the UN Expert Group Meeting Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. Now available in English and French, this report highlights family experiences, connections and well-being during COVID-19, as well as the current resources, policies, programs and initiatives in place to support families and family life.

Families “Safe at Home” details federal, provincial and territorial resources created to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families. In addition to government responses, a summary is provided of the diverse range of available services that support families from pre-parenthood to adolescence and that serve parents across Canada, including those who belong to Indigenous, 2SITLGBQ+ and newcomer communities.

The Expert Group Meeting was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA), where experts from diverse fields from around the world connected virtually to discuss COVID-19 impacts, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada

Nora Spinks, Sara MacNaull, Jennifer Kaddatz

Toward the end of 2019, news began to spread around the world about the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Like many other countries, Canada was facing the possibility of weeks and months with families living in isolation in their homes, changes to school and work schedules, and unknown impacts on family connections and well-being.

In 2020, global citizens around the world are living in and adapting to new ways of life while remaining “safe at home” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadians have been striving to respect physical and social distancing guidelines implemented by our governments and based on the recommendations of public health officials since March 10, 2020. For many families, the past three months have included parenting in close quarters with high levels of uncertainty and unpredictability while managing work commitments, fulfilling care responsibilities inside and outside the home, and homeschooling children of all ages. Despite the inability to plan and the unknowns about what the next few weeks and months might look like, most families are maintaining good physical and mental health, taking care of one another and weathering the storm with their neighbours and communities at a distance.

During these unprecedented times, the Vanier Institute of the Family has adjusted its focus to understanding families in Canada in a time of drastic social, economic and environmental change. The daily activities of individuals and families in Canada, what they are thinking, how they are feeling and what they are doing are all important factors to be addressed and understood in the short, medium or long term.

Accordingly, representatives from the Vanier Institute were co-founders of the COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, a multidisciplinary group of some of Canada’s leading experts along with some of their international colleagues. The network has identified important issues, key indicators and relevant socio-demographics to generate evidence-based responses addressing the social and economic dimensions of the COVID-19 crisis in Canada. As well, to understand the experiences of families during the pandemic, the Vanier Institute has internally mobilized knowledge from other available sources, including quantitative data from both government and non-governmental agencies, such as Statistics Canada and UNICEF Canada, as well as qualitative information from individuals, families and organizations across the nation. Analyses of these findings illuminate characteristics of family life both before and during the pandemic, providing insight into what Canadians fear and what they look forward to after public health measures are lifted.

Consistent with its core principles, the Vanier Institute honours and respects the perspectives of diverse families by applying a family lens and Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+), whenever possible.1 By examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and any of its associated “costs and consequences,” including fertility patterns, parenting, family relationships, family dynamics and family well-being, the Institute mobilizes knowledge to those who study, serve and support families to make sound evidence-based decisions when designing and implementing policies and programs for all families in Canada.

COVID-19 Pandemic Experience in Canada

As of May 31, 2020, 1.6 million people have been tested for COVID-19 in Canada (approximately 4.5% of the total population). Among them, 5% have tested positive for the virus, with 8% resulting in death.2 Seniors in long-term care facilities who have died of COVID-19 represent approximately 82% of all deaths linked to the virus.3

Families are like all other “systems” during the pandemic – their strengths and weakness are magnified, amplified and intensified as relationships, interactions and behaviours adapt to changes in routine, habits and experiences. Family connections, family well-being and youth experiences have all been dramatically affected.

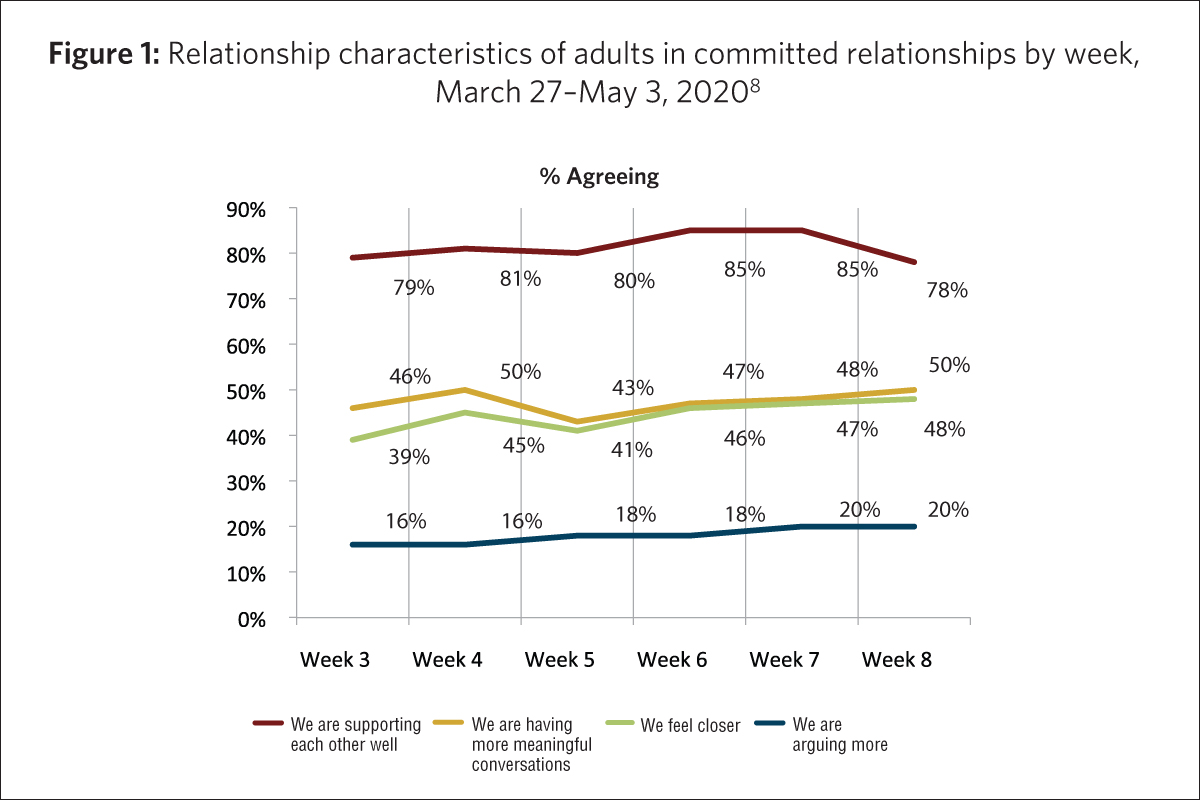

Family Connections

- Approximately 8 in 10 adults (aged 18 and older) who are married or living common-law agreed that they and their spouse were supporting one another well since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1). This figure varies only slightly for those with children or youth at home (77%) compared with those without children under the age of 18 in the household (82%).4

- Fewer than 2 in 10 adults in committed relationships said they had been arguing more since the start of the pandemic (Fig. 1).5

- Six in 10 parents reported they were talking to their children more often than before the lockdown began.6

- When young kids were in the house, adults were almost twice as likely as those with no children or youth at home to have increased their time spent making art, crafts or music.7

On the other hand…

- One-third of adults said that they were very or extremely concerned about family stress from confinement.9

- 10% of women and 6% of men were very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home.10, 11

- About 1 in 5 Canadians had senior relatives living in a nursing home or facility, with 92% of females and 78% of men being very or somewhat concerned for their health.12

Family Well-Being

- More than three-quarters of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants reported either very good or excellent (46%) or good (31%) mental health during pandemic, in a survey conducted April 24–May 11, 2020.13

- Nearly half (48%) of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants said that their mental health was “about the same,” “somewhat better” or “much better” than it had been prior to the start of the pandemic.14

- About half of adults said they felt anxious or nervous or felt sad “very often” or “often” since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis.15

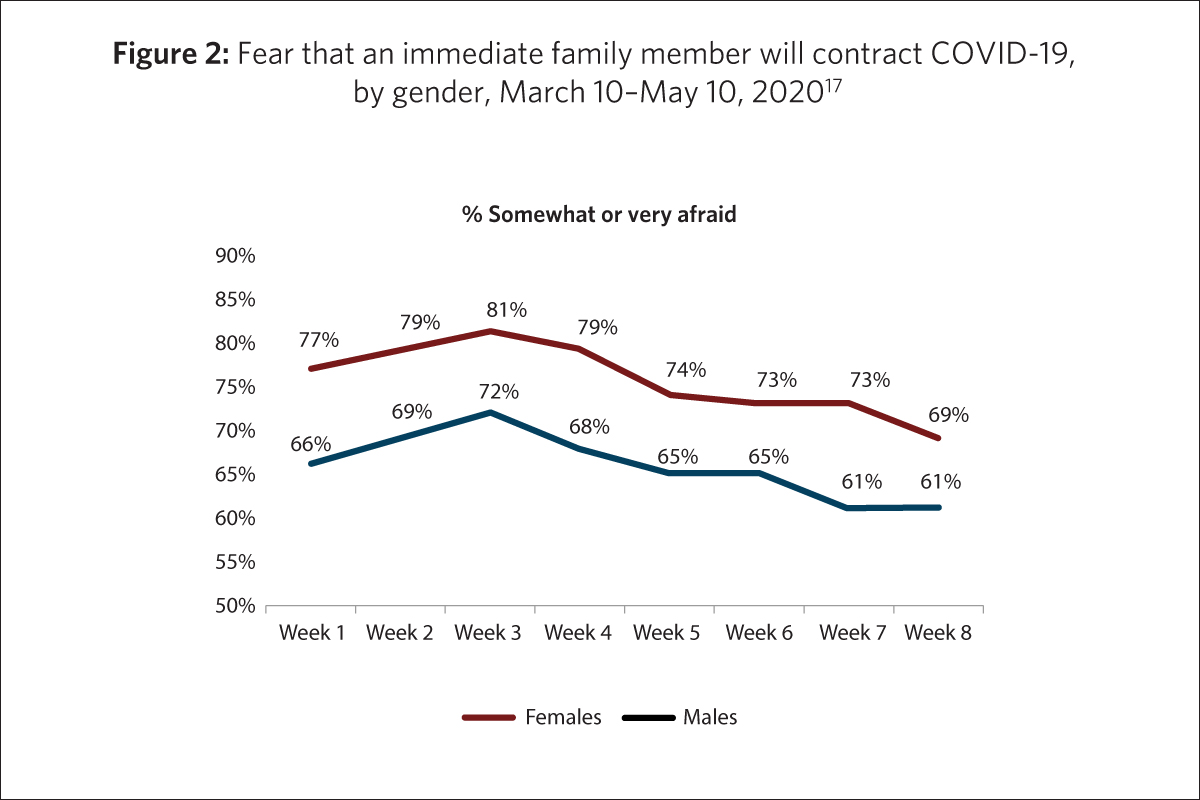

- Regardless of age group or week surveyed, women expressed being more afraid than men that they would contract the virus or that someone in their immediate family would contract it (Fig. 2).16

- Canadians were more afraid of a loved one contracting COVID-19 than they were of contracting it themselves. Adults who were “very” or “extremely”concerned about:

- their own health: 36%

- health of someone in household: 54%

- health of vulnerable people: 79%

- overloading the health care system: 84%18, 19

- More than 4 in 10 of adults living with children under the age of 18 in their home said they “very often” or “often” have had difficulty sleeping since the beginning of the pandemic.20

- When asked to describe how they have been primarily feeling in recent weeks, Canadians were most likely to say they were worried (44%), anxious (41%) and bored (30%); fully one-third (34%) also said they were “grateful.”21

- Women were considerably more likely than men to report experiencing anxiety or nervousness, sadness, irritability or difficulty sleeping during the pandemic.22

- Adults across all age groups continued to exercise during the pandemic, as two-thirds of adults aged 18–34 reported that they were exercising equally as often or more often during the pandemic than they were before it started. The figures were similar for adults aged 35–54 (62%) and aged 55 and older (65%).23

- Younger adults (aged 15–49) were more likely to report an increase in junk food consumption than older adults.24

- Food banks saw a 20% average increase in demand, with some local food banks, such as those in Toronto, Ontario, seeing increases as high as 50%.25

- More than 9 in 10 people aged 15 and older said that the pandemic had not changed their consumption of tobacco nor cannabis.26 Just under 8 in 10 reported that the pandemic had not affected their drinking habits.27

Youth Experiences

- Youth aged 12–19 said they got most of their information about COVID-19 and public health measures from their parents.28

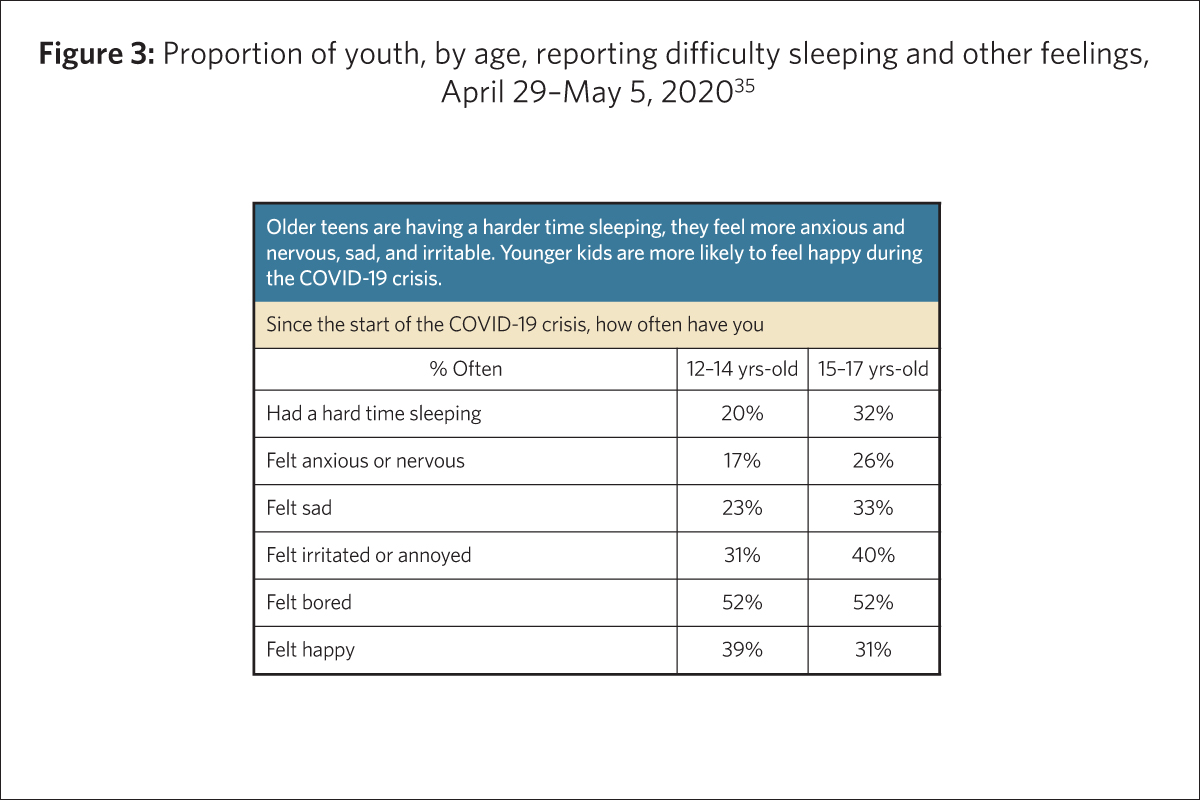

- Older youth, aged 15–17, were more anxious than younger youth, aged 12–14.29

- Among youth aged 15–17, 50% reported that the pandemic had had “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their mental health, compared with 34% of youth aged 12–14. Approximately 4 in 10 youth aged 12–17 reported “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their physical health.30

- Approximately half of children and youth across all age groups missed their friends the most while in isolation.31

- Though 75% of youth claimed to be keeping up with school while in isolation, many were also unmotivated (60%) and disliked the arrangement (57%) (i.e. online learning; virtual classrooms).32

- Many youth said they were doing more housework or chores during the pandemic.33

- Older teens (aged 15–17) were having more difficult sleeping, feeling more anxious or nervous, sad and irritable. Younger teens (aged 12–14) were more likely to feel happy than older teens (Fig. 3).34

COVID-19 Pandemic Response in Canada

Since March 2020, the provincial, territorial and federal governments have announced diverse benefits, credits, programs, initiatives and funds to support families across Canada. The purpose of these recent resources is to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families during this period of uncertainty, including the following:

Temporary Increase to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB)

The Canada Child Benefit (CCB) is a tax-free monthly payment made to eligible families to help with the cost of raising children under the age of 18. The amount of the benefit varies depending on the number of children, the age of the children, marital status and family net income from the previous year’s tax return. The CCB may include the child disability benefit and any related provincial and territorial programs.36

For families already receiving the CCB, an additional $300 per child was added to the benefit in May 2020. For example, a family with two children received $600, in addition to their regular monthly CCB payment, which could be up to a maximum of $553.25 per month per child under the age of 6 and $466.83 per month per child aged 6–17.37, 38

Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)

In April 2020, Canada’s federal government established the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to support workers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The CERB provides $2,000 every four weeks to workers who have lost their income as a result of the pandemic. Eligibility includes adults who have lost their job or who are sick, quarantined or taking care of someone who is sick with COVID-19. It applies to wage earners, contract workers and self-employed individuals who are unable to work. The benefit also allows individuals to earn up to $1,000 per month while collecting CERB.39

As a result of school and child care closures across Canada, the CERB is available to working parents who must stay home without pay to care for their children until schools and child care can safely reopen and welcome back children of all ages.

As of early May 2020, more than 7 million Canadians had applied for CERB since its introduction.40

Mortgage Payment Deferral

Homeowners across Canada who are facing financial hardship due to lack of work or decreased income during the pandemic may be eligible for a mortgage payment deferral of up to six months.

The payment deferral is an agreement between individuals and their mortgage lender, which includes a suspension of all mortgage payment for a specified period of time.41

Special Good and Services Tax Credit

The Goods and Services Tax credit is a tax-free quarterly payment that helps individuals and families with low and modest incomes offset all or part of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) or the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) that they pay.42

In April 2020, the federal government provided a one-time special payment in April 2020 to those receiving the Goods and Services Tax credit. The average additional benefit was nearly $400 for single individuals and close to $600 for couples.43

Temporary wage top-up for low-income essential workers

The federal government is providing $3 billion to increase the wages of low-income essential workers. Examples of essential workers (though variable by province or territory) may include health care professionals, long-term care facility employees and grocery store employees.

Each province or territory is responsible for determining which workers are eligible for this support and how much they will receive.44

Emergency Relief Support Fund for Parents of Children with Special Needs (Province of British Columbia)

To support parents of children with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of British Columbia created a new Emergency Relief Support Fund. The fund will provide a direct payment of $225 per month to eligible families from April to June 2020 (three months).

The payment may be used to purchase supports that help alleviate stress, such as meal preparation and grocery shopping assistance; homemaking services; caregiver relief support and/or counselling services, online or by phone.45

COVID-19 Income Support Program (Province of Prince Edward Island)

In April 2020, the Government of Prince Edward Island announced financial support for individuals whose income has been impacted as a direct result of the public health state of emergency, as well as additional protocols to keep residents safe.

The COVID-19 Income Support Program will help individuals bridge the gap between their loss of income and Employment Insurance (EI) benefits or the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) by providing a one-time, taxable payment of $750.46

Support for Families Initiative (Province of Ontario)

In April 2020, the Government of Ontario announced direct financial support to parents while Ontario schools and child care centres remain closed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new Support for Families initiative offers a one-time payment of $200 per child aged 0–12 and $250 for those aged 0–21 with special needs.47

Emergency Allowance for Income Assistance Clients (Northwest Territories)

For Income Assistance clients registered in March 2020, the Government of the Northwest Territories provided a one-time emergency allowance to help with a 14-day supply of food and cleaning products as the stores have them available.

The Income Assistance (IA) program is designed for residents who are aged 19 and older and who have a need greater than their income. The emergency allowance received by individuals was $500 and for families it was $1,000.48

Parenting in Canada: Government Priorities, Policies, Programs and Resources

The Government of Canada and the provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments provide support to parents in Canada in myriad ways. In addition to the supports provided to assist families during the COVID-19 pandemic, as described in the previous section, a selection of current priorities, policies, programs and resources that are current and existed pre-pandemic are highlighted below.

Early Learning and Child Care

Early learning and child care needs across Canada are vast and diverse. The Government of Canada is investing in early learning and child care to ensure children get the best start in life. As a first step, the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers responsible for early learning and child care have agreed to a Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. The new Framework sets the foundation for governments to work toward a shared long-term vision where all children across Canada can experience the enriching environment of quality early learning and child care. The guiding principles of the Framework are to increase quality, accessibility, affordability, flexibility and inclusivity. A distinct Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework was co-developed with Indigenous partners, reflecting the unique cultures and needs of First Nation, Inuit and Métis children across Canada.49, 50

Before- and After-school Care

Canada’s federal government priorities currently include working with the provinces and territories to invest in the creation of up to 250,000 additional before- and after-school spaces for children under the age of 10, at least 10% of which would allow for care during extended hours. Priorities also include decreasing child care fees for before- and after-school programs by 10%.51

Just for You – Parents

“Just for You – Parents” is a federally created web-based list of resources for parents on topics, including alcohol, smoking and drugs; child abuse; childhood diseases and illnesses; educational resources; family issues; healthy living; mental health; parenting tips (childhood development); school health; and work–life balance. Each topic includes a range of subtopics that direct parents through links to the most up-to-date information available in Canada on issues of importance to them and their children.52

Guaranteed Paid Family Leave Program

In 2019, the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development was tasked to work with the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion to improve and integrate the existing Employment Insurance-based system of maternity and parental benefits and work with the province of Quebec on the effective integration with its own parental benefits system.53

- Maternity and Parental Benefits Administered through the Employment Insurance (EI) program in Canada (excluding Quebec), maternity and parental benefits include financial support (i.e. income replacement for eligible workers) to new mothers and parents following the birth or adoption of a child. The number of weeks and amount paid to each parent varies depending on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the government).54 In Quebec, the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) administers the maternity, paternity, parental and adoption benefits. The amount received by parents is also dependent on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the provincial government). In 2019, the average weekly standard parental benefit rate in Canada reached $464.00 per month.55, 56

Modernizing Canada’s Federal Family Laws

On June 21, 2019, Royal Assent was given to amend Canada’s federal family laws related to divorce, parenting and enforcement of family obligations. The first update to family laws in more than 20 years, this initiative will make federal family laws more responsive to the needs of families through changes to the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act, and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act. The majority of the amendments to the Divorce Act will come into force July 1, 2020, while amendments to the other Acts will take place over two years. The legislation has four key objectives: promote the best interests of the child; address family violence; help to reduce child poverty; and make Canada’s family justice system more accessible and efficient.57

Provincial and Territorial Child Protection Legislation and Policy

The federal, provincial and territorial governments of Canada recognize the importance of surveillance in providing evidence about the contexts, risk factors and types of child maltreatment to inform policy, program, service and awareness interventions. Through their child welfare ministries, the provincial and territorial governments are responsible for assisting children in need of protection; they are also the primary source of administrative data and information related to reported child maltreatment. Preventing and addressing child maltreatment is a complex undertaking that involves the engagement of governments at all levels and in various sectors, including social services, policing, justice and health. At the federal level, the Family Violence Initiative brings together multiple departments to prevent and address family violence, including child maltreatment. The Department of Justice is responsible for the Criminal Code, which includes several forms of child abuse. As the Criminal Code currently stands – which has been debated by advocates and parents alike – section 43 legally allows for the use of corporal punishment on children by select individuals as long as does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstances.58, 59

Nobody’s Perfect

Introduced nationally in 1987 and currently owned by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Nobody’s Perfect is a facilitated parenting program for parents of children aged 0–5. The program is designed to meet the needs of parents who are young, single, or socially or geographically isolated, or who have low income or limited formal education, and is offered in communities by facilitators to help support parents and young children. It provides parents of young children with a safe place to build on their parenting skills, an opportunity to learn new skills and concepts, and a place to interact with other parents who have children the same age.60

Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities

The Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) Program is a national community-based early intervention program funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada. AHSUNC focuses on early childhood development for First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their families living off-reserve. Since 1995, AHSUNC has provided funding to Indigenous community-based organizations to develop and deliver programs that promote the healthy development of Indigenous preschool children. It supports the spiritual, emotional, intellectual and physical development of Indigenous children, while supporting their parents and guardians as their primary teachers.61

Parenting in Canada: Pre-Parenthood to Adolescence62

For expectant parents (or those considering parenthood), the months leading up to the birth or adoption of a child can be exciting and overwhelming. There are many things to prepare for – including the unexpected – in advance of the little one’s arrival. Support in Canada often includes regular and free visits with an obstetrician-gynecologist, a midwife or other registered health care professionals to ensure healthy growth and development. Programs and services are also available in communities across Canada to prepare and plan for parenthood.

- 2SITLGBQ+ Family Planning Weekend Intensive This two-day program is structured to explore pathways to parenthood and strategies for achieving one’s vision of kinship and family. Participants are encouraged to ask questions, gather information and build community, while exploring topics such as co-parenting, multi-parent and single parent families, pregnancy, kinship struggles and self-advocacy. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

- Preparing for Parenthood Geared toward parents-to-be, this program offers information about how to remain healthy during pregnancy and what to expect during the early days and weeks of parenthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Mommies & Mamas 2B/Daddies & Papas 2B This 12-week course is geared toward gay/lesbian, bisexual and queer men/women who are considering parenthood. The course includes resources and discussions to explore practical, emotional, social, ethical, financial, medical, legal, political and intersectional issues related to becoming a parent. Topics explored include co-parenting, surrogacy, parenting arrangements, non-biological and adoptive parenting, fertility awareness, pre-natal care options and legal issues. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

Newborns and Infants

Caring for a newborn or infant comes with many triumphs and challenges. For parents, programs and services are offered across the country, many free of charge, including visits with pediatricians and registered health care professionals. Postnatal care services vary across regions and communities, which may include informational supports, home visits from a public health nurse or a lay home visitor, or telephone-based support (e.g. Telehealth) from a public health nurse or midwife.63 Organizations across the country also offer drop-in programs for parents, grandparents and caregivers to support healthy child development and attachment.

- Roots of Empathy At the heart of the program are an infant and parent who visit a local classroom every three weeks over the course of the school year. Along with a trained Roots of Empathy Instructor, students observe the baby’s development and feelings. This program provides opportunities for parents and infants to take part in teaching emotional literacy and empathy to children aged 5–12, while strengthening their own bonds to each other. (Roots of Empathy)

- Parenting My Baby Tailored to new parents to provide opportunities to learn, participate in discussions on various topics related to infancy, child development and parenting, as well as opportunities to meet fellow new parents. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Bellies & Babies This drop-in group is geared toward pregnant women and new parents with babies from birth to one year. The group provides individual and peer support for pregnant women and postnatal mothers and provides resources and support to new parents. Resources include topics such as the importance of early secure attachment, nutrition, breastfeeding, mental health, infant development and parenting. (Sunshine Coast Community Services Society)

- Young Parents Connect This informal support group is geared toward parents and parents-to-be under the age of 26. It provides an opportunity to meet other young parents, ask questions and share concerns. Each session also includes a fun, interactive activity for children and parents together. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

Toddlers and Preschoolers

Programs for toddlers and preschoolers include a variety of activities to engage both children and their parents to support healthy child development and parent–child attachment. Programs may include drop-in activities, such as those offered by the Boys and Girls Club of Canada or through municipal recreation centres. The drop-in program – offering dancing, story time, arts and crafts and much more – provides opportunities for parents, caregivers and grandparents to take part in learning activities to create, explore and play. Drop-ins welcome moms, dads, grandparents and caregivers, while also providing opportunities to meet and connect with others within the community.

- Parenting Skills 0–5 This online parenting class is designed for families experiencing challenges, providing parents with a foundational understanding to raise their children during the first five years. Topics in this class include child development and personality, discipline, sleep and nutrition. Parenting skills classes are also available for parents with children aged 5–13 and 13–18. (BC Council for Families)

- Fathering Tailored to fathers, including new dads, those experiencing separation or divorce, teen dads and Indigenous dads, this series of resources provides information on how to navigate the various stages of childhood while providing practical tips in support of both fathers and their children. (BC Council for Families)

- Dad HERO (Helping Everyone Realize Opportunities) This project consists of an 8-week parenting course (offered in select correctional institutions in Canada) and a Dad Group both inside the facility for incarcerated fathers and in the community for fathers who were previously incarcerated. This project was designed to educate and teach fathers about parenting, child development and growth, and their role in their children’s lives. Dad HERO provides parenting education and support connecting fathers with their children and improve their mental health and well-being. (Canadian Families and Corrections Network)

School-Aged Children

As children begin and progress through the formal education system in Canada, they encounter various people (i.e. peers, educators) and influences (i.e. social media). Programs and services for parents of school-aged children provide practical tips, informative resources and opportunities to meet and engage with fellow parents in their communities.

- Parenting School-Age and Adult Children This resource was created to support newcomer parenting programs and address some of the challenges that newcomer parents and caregivers may have with parenting in Canadian society. The goal of the program is to gain effective communication skills, better understand the Canadian school systems and create a safe space for parents and caregivers to address their questions and concerns relating to children integrating into the wider Canadian society and culture. (CMAS)

- Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting This workshop series promotes non-violent discipline and respects the child as a learner. It is an approach to teaching that helps children succeed, gives them information and supports their growth from infancy to adulthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Newcomer Parent Resource Series Available in 16 languages (e.g. Urdu, Arabic and Russian), this resource series explores various topics of interest tailored to meet the unique needs of immigrant and refugee parents of young children. Topics include Keeping Your Home Language, Guiding Your Child’s Behaviour, Helping Your Child Cope with Stress, Children Learn Through Play, and Listening to and Talking with Your Child. (CMAS)

- Parenting after Separation: Meeting the Challenges This six-week program is geared toward parents who have recently experienced separation from their partner. Parents meet once a week to discuss the challenge associated with parental separation and divorce and learn practical strategies to support their children. (Family Service Toronto)

- Foster Parent Support This program provides direct, outreach-oriented support to foster parents/caregivers and the children/youth in their care. Support workers work directly with the family in their home, in the community or via phone. This program is intended to be flexible in meeting the unique needs of each foster family and can offer a variety of supports, including teaching conflict resolution skills, de-escalation techniques, collaborative problem solving and using strength-based and trauma-informed approaches. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

Adolescents

Parenting a teen can be challenge, especially in the rapidly evolving era of technology. Adolescence can also be a difficult time for teens who may be questioning their identity, their purpose and envisioning their goals for the future. Programs for parents of teens recognize the importance of supporting children through adolescence as they transition into adulthood.

- Parents Together This is an ongoing professionally facilitated education and group support program for parents who are experiencing challenges while parenting a teen. This program helps parents address their feelings (e.g. guilty, isolation) and provides opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge that can help decrease conflict in the home between parents and their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Transceptance This is an ongoing monthly peer support group for parents and caregivers of transgender youth and young adults. The support provides support and education, reduces isolation and stress, and shares information, including strategies for dealing or coping with disclosures. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

- Parenting in the Know This 10-week education and support program to learn more about adolescent development, teen mental health and other common issues that parents experience. Local guest speakers, community resources, practical ideas and connections with others experiencing similar issues help parents feel better equipped to parent their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Families in TRANSition (FIT) This 10-week program is geared toward parents/caregivers of trans- and gender-questioning youth (aged 13–21) who have recently learned of their child’s gender identity. The program provides support to parents/caregivers to gain tools and knowledge to help improve communication and strengthen their relationship with their youth; learn about social, legal and physical transition options; strengthen skills for managing strong emotions; explore societal/cultural/religious beliefs that impact trans youth and their families; build skills to support their youth and family when facing discrimination, transphobia and/or transmisogyny; and promote youth mental health and resilience. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

Looking Ahead

Families are the most adaptive institution in the world. They are resilient, diverse and strong.

As countries around the world begin to focus on the post-pandemic future, families and family experiences will continue to evolve and adapt. Parents may return to work outside the home, when children return to school and child care, and many will continue to work remotely. Some extracurricular activities will return, while classes like martial arts may continue to be delivered online.

While predicting the future has never been easy, the impact and realities of the global pandemic on families is not yet known, and programs and services may require adjustments in order to support the physical, mental, emotional and social well-being of parents and their children through a trauma-informed lens. Though many families may have been safe at home, some experienced an increase in violence, stress, isolation and anxiety.

Policy and program development, benefits, resources, supports and services will require a comprehensive understanding of families in Canada, their experiences and aspirations; thoughts and fears; and hopes and dreams during this period in time which has evolved and may forecast what lies ahead. The research and innovation behind the many initiatives, including those included in this paper, will help guide evidence-informed decisions; the development, design and implementation of evidence-based programs, policies and practices; and evidence-inspired innovation at all levels of government, community organizations, workplaces and faith communities to ensure families in Canada thrive now and into the future.

Nora Spinks is CEO at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Sara MacNaull is Program Director at the Vanier Institute ofthe Family.

Jennifer Kaddatz is a senior analyst at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Published on June 23, 2020

______________________________________________________________________________

This report was originally published on June 23, 2020 on the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA) website as part of the Expert Group Meeting on Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. This event was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of UNDESA to convene diverse experts from around the world virtually to discuss the impact of COVID-19 on families, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Appendix A: Organizational and Program Overview

Founded in 1977, the BC Council for Families (BCCF) has been developing and delivering family support resources and training programs to professionals across the province of British Columbia as a way to share knowledge and build community connections. The BCCF offers online classes, resources and programs to support parents and children from infancy to adulthood.

The Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada offer educational, recreational and skills development programs and services to children and youth in communities across Canada. The Clubs strive to provide safe, supportive places where children and youth can experience new opportunities, overcome barriers, build positive relationships and develop confidence and skills for life. Many Clubs also offer programs and services to parents to support child development and attachment.

__________

Founded in 1992, Canadian Families and Corrections Network (CFCN) aims to build stronger and safer communities by assisting families affected by criminal behaviour, incarceration and reintegration. Their work includes developing resources for children, parents and families to understand the correctional system and process in Canada and to support families as they manage the experience of having a loved one incarcerated.

__________

The Central Toronto Youth Services (CTYS) is a community-based, accredited Children’s Mental Health Centre that serves many of Toronto’s most vulnerable youth. Their programs and services meet a diversity of needs and challenges that young people experience, such as serious mental health issues; conflicts with the law; coping with anger, depression, anxiety, marginalization or rejection; and issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.

__________

Founded in 2000, CMAS focuses on caring for immigrant and refugee children by sharing their expertise with immigrant serving organizations and other organizations in the child care field. They currently identify gaps in service and work to create solutions; establish and measure the standards of care; and support services for newcomer families through resources, training and consultations.

__________

EarlyON Child and Family Centres provide opportunities for children from birth to age 6 to participate in play and inquiry-based programs, and support parents and caregivers in their roles. The goal of the EarlyON is to enhance the quality and consistency of child and family programs across Ontario.

__________

For more than 100 years, Family Service Toronto has been supporting individuals and families through counselling, community development, advocacy and public education programs. This includes direct service work of intervention and prevention such as counselling, peer support and education; knowledge building and exchanging activities; and system-level work, including social action, advocacy, community building and working with partners to strengthen the sector.

__________

Founded in 2001 and housed at the Sherbourne Health Centre (in Toronto, Ontario), the LGBTQ+ Parenting Network supports lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer parenting through resource development, training and community organizing. The Network coordinates a wide range of programs and activities with and on behalf of LGBTQ parents, prospective parents and their families, including newsletters, print resources, support groups, social events, research projects, advocacy and training.

__________

For more than 30 years, Roots of Empathy has strived to build caring, peaceful and civil societies through the development of empathy in children and adults. The goals of Roots of Empathy are to foster the development of empathy; develop emotional literacy; reduce levels of bullying, aggression and violence; promote children’s pro-social behaviours; increase knowledge of human development, learning and infant safety; and prepare students for responsible citizenship and responsive parenting.

__________

Since 1974, Sunshine Coast Community Services Society (SCCSS) has provided services for individuals and families along the Sunshine Coast (British Columbia). Programs are focused around child and family counselling; child development and youth services; community action and engagement; domestic violence; and housing.

Notes

- GBA+ is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ also considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability. Link: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/index-en.html

- Government of Canada. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update” (May 31, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html

- Marc Montgomery, “COVID-19 Deaths: Calls for Government to Take Control of Long Term Care Homes,” Radio-Canada International (May 25, 2020). Link: https://www.rcinet.ca/en/2020/05/25/covid-19-deaths-calls-for-government-to-take-control-of-long-term-care-homes/

- A survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted weekly starting in March (beginning March 10–12), through April and May 2020, included approximately 1,500 individuals aged 18 and older, interviewed using computer-assisted web-interviewing technology in a web-based survey. Some weekly surveys included booster samples of specific populations. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to gender, age, mother tongue, region, education level and presence of children in the household in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (web panel in this case). However, for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,512 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.52%, 19 times out of 20.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19,” The Daily (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200408/dq200408c-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Though data varies, reports have claimed that consultations by the federal government reveal a 20% to 30% increase in violence rates in certain regions which is supported by organizations such as Vancouver’s Battered Women Support Services that has reported a 300% increase in calls related to family violence during the pandemic. Links: https://bit.ly/2OKYsK0, https://bit.ly/2ZOiF8f.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadians’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic” (May 27, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200527/dq200527b-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada’s healthcare system is publicly funded, which means that all Canadian residents have reasonable access to medically necessary hospital and physician services without paying out-of-pocket. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Worry, Gratitude & Boredom: As COVID‑19 Affects Mental, Financial Health, Who Fares Better; Who Is Worse?” (April 27, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-mental-health/

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada, “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19.”

- Beatrice Britneff, “Food Banks’ Demand Surges Amid COVID-19. Now They Worry About Long-Term Pressures,” Global News (April 15, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/3boEHRe.

- On October 17, 2018, the use of cannabis for recreation and medicinal purposes among adults became legal in Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/cannabis/

- Michelle Rotermann, “Canadians Who Report Lower Self-Perceived Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic More Likely to Report Increased Use of Cannabis, Alcohol and Tobacco,” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada (May 7, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.htm.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, in partnership with Experiences Canada and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted a nation-wide COVID-19 web survey of the 12- to 17-year-old population in Canada from April 29 to May 5. A total of 1191 responses were received, and the probabilistic margin of error was ±3%. Link: https://acs-aec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Youth-Survey-Highlights-May-21-2020.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Kids & COVID-19: Canadian Children Are Done with School from Home, Fear Falling Behind, and Miss Their Friends” (May 11, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-kids-opening-schools/

- Ibid.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada Revenue Agency. “Canada Child Benefit” (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan” (May 28, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/economic-response-plan.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada Child Benefit: How Much You Can Get” (January 27, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca

/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview/canada-child-benefit-we-calculate-your-ccb.html - Government of Canada. “Expanding Access to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Proposing a New Wage Boost for Essential Workers” (April 17, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2020/04/expanding-access-to-the-canada-emergency-response-benefit-and-proposing-a-new-wage-boost-for-essential-workers.html.