Projects

Families Count 2024

Vanier Institute’s new resource explores three decades of change, continuity, and complexity among families in Canada. Released during the International Year of the Family’s 30th anniversary, Families Count 2024 provides statistical portraits of families in Canada, highlights trends over time, and offers insights on what it all means for families and family life.

Chapter 6 – Polyamorous families have broadened family law

Polyamorous families are one of the growing number of diverse family structures in Canada. Polyamory is a form of consensual non-monogamy (CNM). This umbrella term describes any type of intimate relationship in which the partners allow sexual and/or emotional relationships outside their couple relationship.1 While some of these relationship types are focused on the partners allowing for sexual experiences outside the couple without romantic or emotional attachments, polyamory is distinguished from other CNM relationship types in that it allows for them.

Like all relationships, polyamorous relationships are diverse. The specific structures, the types of relationships (e.g., sexual and/or romantic, regular, or infrequent), and the roles and expectations within can vary greatly depending on the preferences of the people involved. Some polyamorous families are centred around long-term, committed relationships with two or more people, while others may have a mix of short-term and long-term relationships with varying degrees of intimacy and commitment.2

Polyamorous relationships may include—but do not require—a married or common-law couple, but Canadian law does not recognize intimate relationships between more than two people. Since polyamorous relationships are not counted in the Census nor included in the definition of a census family household, there is a data gap in their prevalence and composition. Surveys have shown that approximately one in five people in Canada and the United States have practised consensual non-monogamy at some point, with young adults more likely to have done so.1 Research shows that sexual minorities are more likely to practise CNM than heterosexual people.3

Polyamorous families are increasingly being recognized in Canadian law. This has resulted from legal cases in which more than two people in a polyamorous relationship shared parental responsibilities but faced difficulties because their family structure was not being recognized in most law or policies. For example, the Divorce Act defines “spouse” as “either of two persons who are married to each other,” while the Civil Marriage Act provides that marriage is “the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others.”4

Several court cases in recent years have broadened parental rights to also include families with more than two parents and addressed the exclusion of polyamorous families from Canadian law. In 2018, three unmarried adults in a relationship in Newfoundland and Labrador were declared legal parents of a child born within their polyamorous family. Because the provincial Children’s Law Act did not allow for more than two people to be named as the legal parents of a child, only two could be listed on the child’s birth certificate. In his ruling, Justice Robert Fowler of the Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court’s family division said that “Society is continuously changing and family structures are changing along with it.5 This must be recognized as a reality and not as a detriment to the best interests of the child.”

In 2021, a British Columbia court ruled that a second mother in a polyamorous family be added to a child’s birth certificate. Justice Sandra Wilkinson echoed Fowler’s ruling, stating “I find that there is a gap in the [Family Law Act6]… Put bluntly, the legislature did not contemplate polyamorous families.” She said that it was in the “best interests [of the child] to have all of his parents legally recognized as such.”

Why this matters

This lack of alignment between the diversity of families and the laws that affect them can have an impact on wellbeing; these families often must navigate and interact with systems and institutions that were not designed to support them. This was underscored in a 2021 study in which polyamorous parents in Canada who had recently given birth (or been a partner to someone who did) reported experiencing conflict with, or exclusion from, aspects of social systems designed for monogamous couples/families.7

Other research shows that parents in polyamorous families also report challenges and difficulties regarding parenting and family dynamics, including social acceptance and legal protection, coming out to children, time management, and reconciling family obligations with personal needs.1 Some of these issues may dissipate in future generations if greater awareness and discussion act to reduce stigma and/or if family law continues to become more inclusive of diverse family structures. Many parents in polyamorous families also cited strengths of their family structure, such as having a larger support network for themselves and their children.

Despite the small body of research on polyamorous families in Canada, there is growing awareness and discussion of non-traditional relationship types, including polyamory and other forms of consensual non-monogamy. Polyamorous families are just one of many forms of structural diversity that make families unique. The struggles for legal recognition of parents in these families highlight how laws and policies often trail social change. It remains to be seen how these developments may reshape or otherwise impact family justice policies, legislation, and training for service providers.8 Further research will play an important role in strengthening understanding of polyamorous families and ensuring they are included in laws and policies.

References

- Alarie, M. (2023, December 8). Family and consensual non-monogamy: Parents’ perceptions of benefits and challenges. Journal of Marriage and Family, 1(19). https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12955 ↩︎

- Boyd, J.-P. (2017, April 11). Polyamory in Canada: Research on an emerging family structure. The Vanier Institute of the Family. https://vanierinstitute.ca/polyamory-in-canada-research-on-an-emerging-family-structure ↩︎

- Balzarini, R. N., Dharma, C., Kohut, T., Holmes, B. M., Campbell, L., Lehmiller, J. J., & Harman, J. J. (2018, June 18). Demographic comparison of American individuals in polyamorous and monogamous relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(6), 681-694. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1474333 ↩︎

- Boyd, J.-P. (2016, August 24). Polyamorous families in Canada: Early results of new research from CRILF. https://ablawg.ca/2016/08/24/polyamorous-canada-early-results-from-crilf/ ↩︎

- Lessard, M. (2020, December 1). Les amoureux sur les bancs publics: Le traitement juridique du polyamour en droit québécois. Revue canadienne de droit familial 1, 32(1). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3501938 ↩︎

- British Columbia Birth Registration No. 2018-XX-XX5815, 2021 BCSC 767 (CanLII), (2021, April 23). https://www.canlii.org/en/bc/bcsc/doc/2021/2021bcsc767/2021bcsc767.html ↩︎

- Landry, S., Arseneau, E., & Darling, E. K. (2021, June 1). “It’s a little bit tricky”: Results from the POLYamorous childbearing and birth experiences study (POLYBABES). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(4), 1479-1490.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02025-5 ↩︎ - Levine, E. C., Herbenick, D., Martinez, O., Fu, T.-C., & Dodge, B. (2018, April 25). Open relationships, nonconsensual nonmonogamy, and monogamy among U.S. adults: Findings from the 2012 national survey of sexual health and behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(5), 1439-1450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1178-7 ↩︎

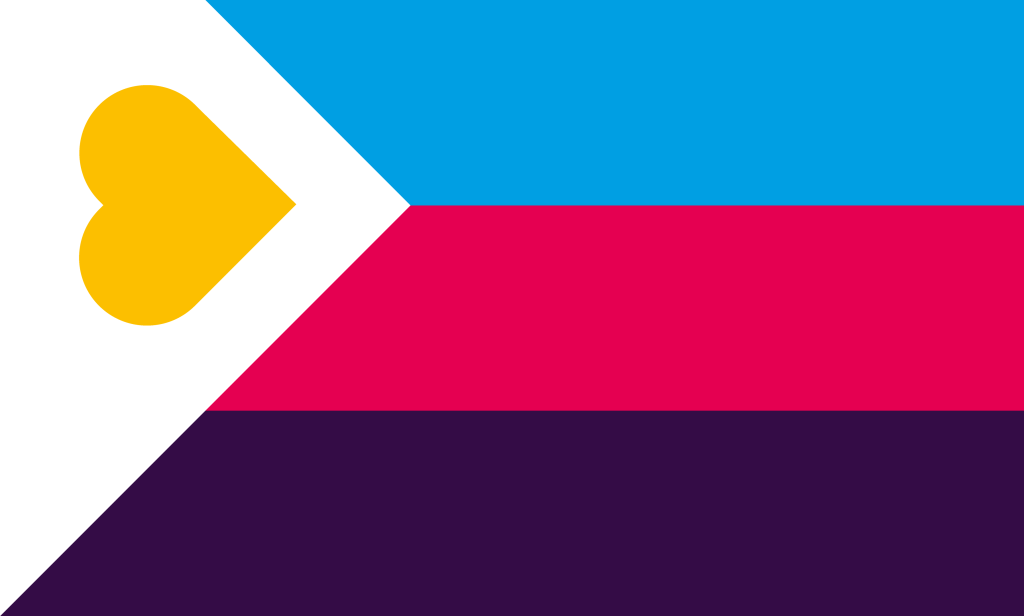

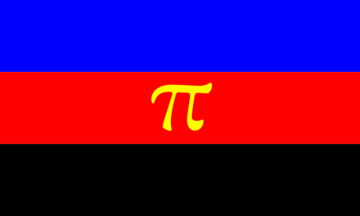

- Polyamproud. (2022). Our new flag. https://www.polyamproud.com/flag ↩︎

- The University of British Columbia. Pride flags. https://equity.ubc.ca/pride-flags ↩︎

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Áine Humble, Professor, Department of Family Studies and Gerontology, Mount Saint Vincent University, for reviewing this chapter.

Families Count 2024 is a publication of the Vanier Institute of the Family that provides accurate and timely information on families and family life in Canada. Written in plain language, it features chapters on diverse topics and trends that have shaped families in Canada. Its four sections (Family Structure, Family Work, Family Identity, and Family Wellbeing) are guided by the Family Diversities and Wellbeing Framework.

The Vanier Institute of the Family

94 Centrepointe Drive

Ottawa, Ontario K2G 6B1

[email protected]

www.vanierinstitute.ca

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International license.

How to cite this document:

Battams, N., & Mathieu, S. (2024). Polyamorous families have broadened family law. In Families count 2024, The Vanier Institute of the Family. https://vanierinstitute.ca/families-count-2024/polyamorous-families-have-broadened-family-law