Key findings from a study about intergenerational caregiving experiences of Canadian Chinese immigrant mothers

Topic: Mothers

Report: Fertility Treatment in Canada

An overview of fertility treatments, policies, and provincial subsidies available in Canada

Then and Now: A 30-Year Look at Families and Work in Canada

Highlights from a resource about families and work in Canada

Report: Mothers’ Return to Work After Childbirth and the Role of Spousal Involvement at Home

A report on the impacts of mothers’ return to work after childbirth on their mental wellbeing

Amy Robichaud

Amy is the daughter to Lore, granddaughter to Rae, and great granddaughter to Rita.

She currently serves as CEO at Mothers Matter Canada and previously as Executive Director of Dress for Success Vancouver, Director of Engagement at the Minerva Foundation for BC Women, and as a development and governance consultant to organizations such as the RBC Foundation, the Global Centre for Pluralism, and the Canadian Mental Health Association.

Amy’s passion for practical ways to generate equity, create economic inclusion, opportunity and prosperity for all informs everything she does, including her volunteerism. She is serving her second term as Chair of the Women’s Advisory Committee for the City of Vancouver where she advises Council and staff on enhancing access and inclusion for women and girls to fully participate in City services and civic life. She has previously served as Chair of the Dress for Success Canada Foundation, and was nominated for the YWCA Vancouver’s Women of Distinction Awards in 2023. She’s a member of the Banff Forum and WNORTH.

Amy and her husband have lived all over Canada and now happily and humbly call the unceded, ancestral and traditional territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and səlilwətaɬ Nations home, along with their pets and overgrown library.

About Mothers Matter Canada

Mothers Matter Canada (MMC) is a national organization dedicated to empowering socially isolated and economically vulnerable mothers by providing innovative, evidence-based programs that support early childhood education, strengthen parent-child bonds, and promote community integration. Through partnerships and advocacy, MMC works to break cycles of poverty and isolation, ensuring mothers and their children achieve their full potential and thrive in welcoming, inclusive communities. When mothers thrive, children flourish, and communities prosper.

Margaret Campbell

Margaret Campbell received her PhD in Social and Cultural Analysis from Concordia University. Her thesis, which was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), explored the diverse ways that people with disabilities make sense of their sexual health and expression. Her PhD research examined barriers to sexual health and expression that many persons with disabilities face and identified diverse ways that they create opportunities for sexual expression despite these barriers. As a post-doctoral fellow with the Vanier Institute, Margaret conducted research aimed at strengthening our understanding of family diversities and family wellbeing, specifically among families with disabilities.

Margaret’s research interests in the wellbeing of families with disabilities and families of those who work in high-risk occupations stem from her upbringing on a family farm in rural Prince Edward Island and her personal experience living with a chronic illness.

Margaret teaches on a part-time basis at St. Thomas University and has a breadth of experience teaching courses in Family Studies, Sociology, and Gender Studies. Her teaching and research practices are informed by critical theories, feminist frameworks, and her belief in the possibility of creating a world that is more equitable, accessible, and, ultimately, more livable.

Robin McMillan

Robin McMillan has spent her career of over 30 years working in the early learning sector. For the first eight years, she worked as an Early Childhood Educator with preschool children. She left the front line to develop resources for practitioners at the Canadian Child Care Federation (CCCF). She has been with the CCCF since 1999 and worked her way from Project Assistant to Project Manager to her present role as Innovator of Projects, Programs and Partnerships. Highlights of her career with CCCF have been managing over 20 national and international projects, including a CIDA project in Argentina and presenting a paper with the Honourable Senator Landon Pearson to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva, Switzerland.

Robin served as a board member on the Ottawa Carleton Ultimate Association for two years, as well as participated in organizing numerous local charity events. She founded and facilitated a local parent support group, Ottawa Parents of Children with Apraxia, and a national group, Apraxia Kids Canada. She is married and has a 17-year-old son with a severe speech disorder, childhood apraxia of speech, and a mild intellectual disability, which launched her into the world of parent advocacy. She was the recipient of the Advocate of the Year Award in 2010 from the Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America.

About the Organization: We are the community in the early learning and child care sector in Canada. Professionals and practitioners from coast to coast to coast belong in our community. We give voice to the deep passion, experience, and practice of Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) in Canada. We give space to excellent research in policy and practice to better inform service development and delivery. We provide leadership on issues that impact our sector because we know we are making a difference in the lives of young children—our true purpose, why we exist—to make a difference in these lives. What gets talked about, explored, and shared in our community is always life changing, and we know that. We are a committed, passionate force for positive change where it matters most—with children.

Maude Pugliese

Maude Pugliese is an Associate Professor at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (Université du Québec) in the Population Studies program and holds the Canada Research Chair in Family Financial Experiences and Wealth Inequality. She is also the scientific director of the Partenariat de recherche Familles en mouvance, which brings together dozens of researchers and practitioners to study the transformations of families and their repercussions in Quebec. In addition, she is the director of Observatoire des réalités familiales du Québec/Famili@, a knowledge mobilization organization that diffuses the most recent research on family issues in Quebec to a broad public in accessible terms. Her current research work focuses on the intergenerational transmission of wealth and of money management practices, gender inequalities in wealth and indebtedness, and how new intimate regimes (separation, repartnering, living apart together, polyamory, etc.) are transforming ideals and practices of wealth accumulation.

Gaëlle Simard-Duplain

Gaëlle Simard-Duplain is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Carleton University. Her research focuses on the determination of health and labour market outcomes. She is particularly interested in the interaction of policy and family in mitigating or exacerbating inequalities, through both intrahousehold family dynamics and intergenerational transmission mechanisms. Her work predominantly uses administrative data sources, sometimes linked to survey data, and quasi-experimental research methods. Gaëlle holds a PhD in Economics from the University of British Columbia.

Donna S. Lero

Donna S. Lero is University Professor Emerita and the inaugural Jarislowsky Chair in Families and Work at the University of Guelph, where she co-founded the Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being. Donna does research in Social Policy, Work and Family, and Caregiving. Her current projects focus on maternal employment and child care arrangements, parental leave policy, and disability and employment, as well as the Inclusive Early Childhood Service System (IECSS) project and the SSHRC project Reimagining Care/Work Policies.

Barbara Neis

Barbara Neis (PhD, C.M., F.R.S.C.) is John Lewis Paton Distinguished University Professor and Honorary Research Professor, retired from Memorial University’s Department of Sociology. Barbara received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Toronto in 1988. Her research focuses broadly on interactions between work, environment, health, families, and communities in marine and coastal contexts. She is the former co-founder and co-director of Memorial University’s SafetyNet Centre for Occupational Health and Safety and former President of the Canadian Association for Work and Health. Since the 1990s, she has carried out, supervised, and supported extensive collaborative research with industry in the Newfoundland and Labrador fisheries including in the areas of fishermen’s knowledge, science, and management; occupational health and safety; rebuilding collapsed fisheries; and gender and fisheries. Between 2012 and 2023, she directed the SSHRC-funded On the Move Partnership (www.onthemovepartnership.ca), a large, multidisciplinary research program exploring the dynamics of extended/complex employment-related geographical mobility in the Canadian context, including its impact on workers and their families, employers, and communities.

Deborah Norris

Holding graduate degrees in Family Science, Deborah Norris is a professor in the Department of Family Studies and Gerontology at Mount Saint Vincent University. An abiding interest in the interdependence between work and family life led to Deborah’s early involvement in developing family life education programs at the Military Family Resource Centre (MFRC) located at the Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Halifax. Insights gained through conversation with program participants were the sparks that ignited a long-standing commitment to learning more about the lives of military-connected family members—her research focus over the course of her career to date. Informed by ecological theory and critical theory, Deborah’s research program is applied, collaborative, and interdisciplinary. She has facilitated studies focusing on resilience(y) in military and veteran families; work-life balance in military families; the bi-directional relationship between operational stress injuries and the mental health and wellbeing of veteran families; family psychoeducation programs for military and veteran families; and the military to civilian transition. She has collaborated with fellow academic researchers, Department of National Defense (DND) scientists, Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) personnel, and others. Recently, her research program has expanded to include an emphasis on the impacts of operational stress on the families of public safety personnel.

Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay

Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay is professor of labour economics/sociology and human resources management at TÉLUQ University (Université du Québec). She was appointed Canada Research Chair on the socio-economic challenges of the Knowledge Economy in 2002 and director of a CURA (Community-University Research Alliance) on the management of social times and work-life balance in 2009 (www.teluq.ca/aruc-gats). She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and of the Centre of Excellence of the Université du Québec, in recognition of the quality of her research and publications. She works on work-life issues, work organization (telework, coworking), and working time arrangements. Diane-Gabrielle has published many books, including a Labour Economics textbook, a Sociology of Work textbook, three books on working time and work-life issues and she has published in various international journals.

Shelley Clark

Shelley Clark, James McGill Professor of Sociology, is a demographer whose research focuses on gender, health, family dynamics, and life course transitions. After receiving her PhD from Princeton University in 1999, Shelley served as program associate at the Population Council in New York (1999–2002) and as an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago (2002–2006). In the summer of 2006, she joined the Department of Sociology at McGill, where in 2012 she became the founding Director of the Centre on Population Dynamics. Much of her research over two decades has examined how adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa make key transitions to adulthood amid an ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Additional work has highlighted the social, economic, and health vulnerabilities of single mothers and their children in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently she has embarked on a new research agenda to assess rural and urban inequalities and family dynamics in the United States and Canada. Her findings highlight the diversity of family structures in rural areas and the implications of limited access to contraception on rural women’s fertility and reproductive health.

Lindsey McKay

Lindsey McKay is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia. She is a feminist sociologist/political economist of care work, health and medicine, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Social justice motivates her research and teaching. She has published in peer-reviewed journals and public platforms on parental leave inequity, organ donation, and curriculum and pedagogy. She is a Co-Investigator in the SSHRC funded Reimagining Care/Work Policies project with a focus on parental leave.

Research Snapshot: Mothers and Part-time Work: Preferences and Experiences

Families Count 2024: Family Structure

Family Structure is the first section of a larger report that will also explore family work, family identity, and family wellbeing.

Research Snapshot: Inuit Mothers’ Visions for Child and Family Wellness in Nunavut, Canada

Summary of a study on how the child welfare system is perceived by Inuit mothers

Research Snapshot: Overwork, Remote Work, and Gendered Dual Devotion to Work and Family

Summary of a study on how dual devotion differs based on gender

Research Snapshot: Challenges of Non-Standard Work Schedules and Childcare

Summary of a study on the unique challenges of managing non-standard work hours and childcare

Research Snapshot: Gaps in Employment Protections for Pregnant Migrants in Canada

Summary of a study on women who were pregnant or gave birth while having precarious immigration status

Research Snapshot: “Family Stories” and Intergenerational Voices of Adoption

A summary of a study on the effects of adoption in adulthood

Research Snapshot: Maternal Labour Force Participation and Separation Anxiety Among Children

Findings from a study about working mothers and separation anxiety among children

Fertility Rate in Canada Fell to (Another) Record Low in 2022

New data shows Canada’s fertility rate is at (another) new record low.

Research Snapshot: Parents, Homeschooling, and Relationship Conflict During COVID-19

Highlights from a study on how providing homeschooling during COVID affected parents

Research Snapshot: Examining Benefits and Barriers to Participating in Family Physical Activity

Highlights from a study about families and active leisure

Three Takeaways from the Quebec Childcare Model

Lessons from Quebec’s childcare system for other provinces and territories in Canada

Research Snapshot: Parenthood and the Gendered Impact of Job Loss

Highlights from a study about gendered consequences of job loss

Policy Brief: Access to Parental Benefits in Canada

A 50-year review of access to parental benefits in Canada

Research Snapshot: Factors Influencing Parents’ Work-Life Balance Inside and Outside Quebec

Findings from a study on work-life balance among parents inside and outside Quebec

VIDEO: Sophie Mathieu on Childcare in Quebec

A new video from Reimagining Care/Work describes childcare in Quebec

Mothers’ Experiences with Fly-In, Fly-Out Work (Families, Mobility, and Work)

Summary of a chapter on the impact of “fly-in, fly-out” work on mothers

November 9, 2022

In their chapter “A Juggling Act: Mothering While FIFO,” authors Griffin Kelly, Maria Fernanda Mosquera Garcia, and Dr. Sara Dorow provide a window into the realities and resiliencies of “mothering while FIFO.” They explore the experiences of mothering among women working under FIFO conditions in western Canada (Alberta and British Columbia). As illustrated by the four stories, these conditions create a variety of challenges for becoming and being a mother across different stages of the life course.

This chapter is one of many contributions included in Families, Mobility, and Work, a compilation of articles and other knowledge products based on research from the On the Move Partnership. Published in September 2022 by Memorial University Press, this book is now available in print, as an eBook, and as a free open-access volume available in full on the Memorial University website.

“Managing camp and home ‘selves’ is crucial to keeping one’s sanity as a [fly-in, fly-out] worker; but the demands of motherhood bring clashes and conflicts to these selves, including trying to imagine a future self beyond ‘work’ and ‘mother.’ […] these stresses and adjustments across disparate times and spaces, and across the realities of boom-and-bust cycles, further extend gendered chains of care, quite often to FIFO mothers’ own mothers.” – Griffin Kelly, Maria Fernanda Mosquera Garcia, and Sara Dorow, PhD

Access Families, Mobility, and Work

Very little research exists on tradeswomen’s experiences of mobile work, let alone on how mobile work shapes their family lives (Nagy and Teixeira, 2020, is one recent exception). In the context of FIFO (fly-in, fly-out) work, attention to women, family, and motherhood has focused on the spouses of FIFO workers (Kaczmarek and Sibbel, 2008; Swenson and Zvonkovic, 2016) and to some degree on women employed in FIFO professional or camp jobs. Our paper combines findings from two current studies of tradeswomen, predominantly in the oil sands of Alberta, to convey experiences of “mothering while FIFO.” We offer four narrative vignettes that illustrate and humanize the challenges and exclusions faced by FIFO tradeswomen engaged in resource extraction work in western Canada at different stages of mothering: when pregnant on the job, while raising children, and during custody disputes. These stories demonstrate the need for examination of the policies and practices of FIFO-based employers that create barriers to work for mothers.

About the authors

Griffin Kelly is a graduate of the MA thesis program of the Department of Sociology at the University of Alberta, where she completed a thesis on tradeswomen’s experiences of gendered harassment in the oil sands of Alberta.

Maria Fernanda Mosquera Garcia is an MA student in Sociology at the University of Alberta. Her research focuses on Latin Americans’ forced displacement and settlement experiences in Canada. She provides research assistantship for the Mobile Work and Mental Health Project, and has participated in the University of Alberta Prison Project as a research assistant.

Sara Dorow, PhD, MA, BA, is Professor and Chair in the Department of Sociology at the University of Alberta. Her research and teaching are in the areas of mobility, migration, family, work, and gender, using an intersectional, qualitative approach. She was Alberta Team Lead for the On the Move Partnership as part of her long-standing study of the social facets of the oil sands region. Previously she studied issues of family, race, and gender in transnational adoption.

Child Care Policy in Canada: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Gordon Cleveland reflects on progress in child care policy and next steps.

Research Snapshot: Gender, Affordable Housing, and the “Poverty Gap” in Canada

Highlights from a study on the experiences of women in Calgary who live in affordable housing

Research Snapshot: Access to Postnatal Healthcare and Supports Among Syrian Refugee Mothers

Findings from a study on the postnatal experiences of Syrian refugee mothers in Canada.

Research Snapshot: Impact of Maternal Incarceration on Family Relationships

Findings from a recent study of the effects of incarceration on mothers and their children.

Research Snapshot: Indigenous Doula Care and the Revitalization of Indigenous Knowledge

A summary of a qualitative study on perinatal and childbirth experiences of Indigenous mothers.

Research Snapshot: Family Dynamics and the Canadian Gender Income Gap

A summary of research on families, gender equality, and income in Canada

Research Recap: Gendered Impacts of Supports for Employed Caregivers

Gaby Novoa summarizes new research on the impact of workplace policies on employed caregivers.

Researcher Spotlight: Kim de Laat

Kim de Laat discusses her research on family diversities, inequality and parental leave.

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Newcomer and Refugee Mothers in Canada – Final Report

Final report on COVID-19 IMPACTS: Newcomer and Refugee Mothers in Canada survey.

In Brief: COVID-19 IMPACTS Through a Gender-based Lens

Diana Gerasimov summarizes new findings on the gendered impacts of the pandemic.

REVIEW: Mothers, Mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from a Pandemic

Alex Foster-Petrocco reviews a new book exploring the experiences of mothers during COVID-19.

Research Recap: Positive Impacts of Parental Benefits on Couple Relationships

Nathan Battams and Gaby Novoa highlight findings from a study on parental leave and divorce.

Report: COVID-19 and Parenting in Canada

September 3, 2020

In June 2020, the Vanier Institute prepared the report Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada for the UN Expert Group Meeting Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. Now available in English and French, this report highlights family experiences, connections and well-being during COVID-19, as well as the current resources, policies, programs and initiatives in place to support families and family life.

Families “Safe at Home” details federal, provincial and territorial resources created to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families. In addition to government responses, a summary is provided of the diverse range of available services that support families from pre-parenthood to adolescence and that serve parents across Canada, including those who belong to Indigenous, 2SITLGBQ+ and newcomer communities.

The Expert Group Meeting was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA), where experts from diverse fields from around the world connected virtually to discuss COVID-19 impacts, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada

Nora Spinks, Sara MacNaull, Jennifer Kaddatz

Toward the end of 2019, news began to spread around the world about the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Like many other countries, Canada was facing the possibility of weeks and months with families living in isolation in their homes, changes to school and work schedules, and unknown impacts on family connections and well-being.

In 2020, global citizens around the world are living in and adapting to new ways of life while remaining “safe at home” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadians have been striving to respect physical and social distancing guidelines implemented by our governments and based on the recommendations of public health officials since March 10, 2020. For many families, the past three months have included parenting in close quarters with high levels of uncertainty and unpredictability while managing work commitments, fulfilling care responsibilities inside and outside the home, and homeschooling children of all ages. Despite the inability to plan and the unknowns about what the next few weeks and months might look like, most families are maintaining good physical and mental health, taking care of one another and weathering the storm with their neighbours and communities at a distance.

During these unprecedented times, the Vanier Institute of the Family has adjusted its focus to understanding families in Canada in a time of drastic social, economic and environmental change. The daily activities of individuals and families in Canada, what they are thinking, how they are feeling and what they are doing are all important factors to be addressed and understood in the short, medium or long term.

Accordingly, representatives from the Vanier Institute were co-founders of the COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, a multidisciplinary group of some of Canada’s leading experts along with some of their international colleagues. The network has identified important issues, key indicators and relevant socio-demographics to generate evidence-based responses addressing the social and economic dimensions of the COVID-19 crisis in Canada. As well, to understand the experiences of families during the pandemic, the Vanier Institute has internally mobilized knowledge from other available sources, including quantitative data from both government and non-governmental agencies, such as Statistics Canada and UNICEF Canada, as well as qualitative information from individuals, families and organizations across the nation. Analyses of these findings illuminate characteristics of family life both before and during the pandemic, providing insight into what Canadians fear and what they look forward to after public health measures are lifted.

Consistent with its core principles, the Vanier Institute honours and respects the perspectives of diverse families by applying a family lens and Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+), whenever possible.1 By examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and any of its associated “costs and consequences,” including fertility patterns, parenting, family relationships, family dynamics and family well-being, the Institute mobilizes knowledge to those who study, serve and support families to make sound evidence-based decisions when designing and implementing policies and programs for all families in Canada.

COVID-19 Pandemic Experience in Canada

As of May 31, 2020, 1.6 million people have been tested for COVID-19 in Canada (approximately 4.5% of the total population). Among them, 5% have tested positive for the virus, with 8% resulting in death.2 Seniors in long-term care facilities who have died of COVID-19 represent approximately 82% of all deaths linked to the virus.3

Families are like all other “systems” during the pandemic – their strengths and weakness are magnified, amplified and intensified as relationships, interactions and behaviours adapt to changes in routine, habits and experiences. Family connections, family well-being and youth experiences have all been dramatically affected.

Family Connections

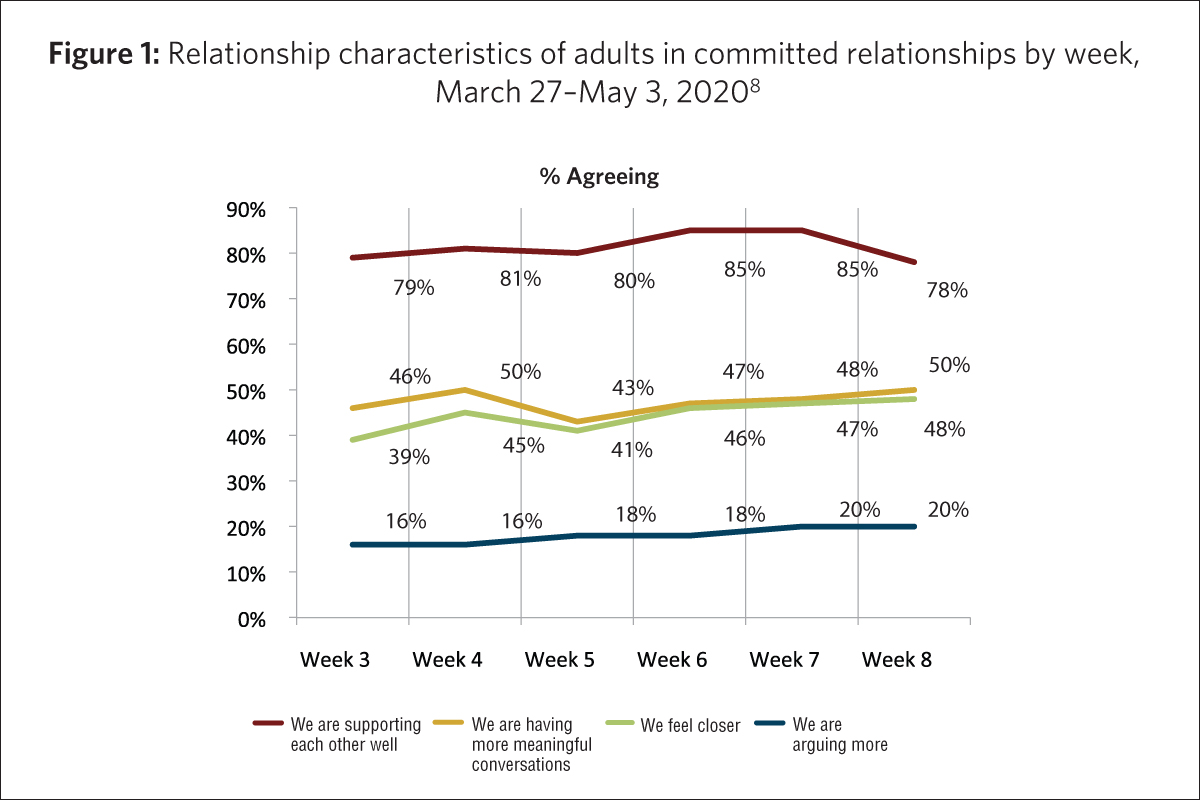

- Approximately 8 in 10 adults (aged 18 and older) who are married or living common-law agreed that they and their spouse were supporting one another well since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1). This figure varies only slightly for those with children or youth at home (77%) compared with those without children under the age of 18 in the household (82%).4

- Fewer than 2 in 10 adults in committed relationships said they had been arguing more since the start of the pandemic (Fig. 1).5

- Six in 10 parents reported they were talking to their children more often than before the lockdown began.6

- When young kids were in the house, adults were almost twice as likely as those with no children or youth at home to have increased their time spent making art, crafts or music.7

On the other hand…

- One-third of adults said that they were very or extremely concerned about family stress from confinement.9

- 10% of women and 6% of men were very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home.10, 11

- About 1 in 5 Canadians had senior relatives living in a nursing home or facility, with 92% of females and 78% of men being very or somewhat concerned for their health.12

Family Well-Being

- More than three-quarters of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants reported either very good or excellent (46%) or good (31%) mental health during pandemic, in a survey conducted April 24–May 11, 2020.13

- Nearly half (48%) of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants said that their mental health was “about the same,” “somewhat better” or “much better” than it had been prior to the start of the pandemic.14

- About half of adults said they felt anxious or nervous or felt sad “very often” or “often” since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis.15

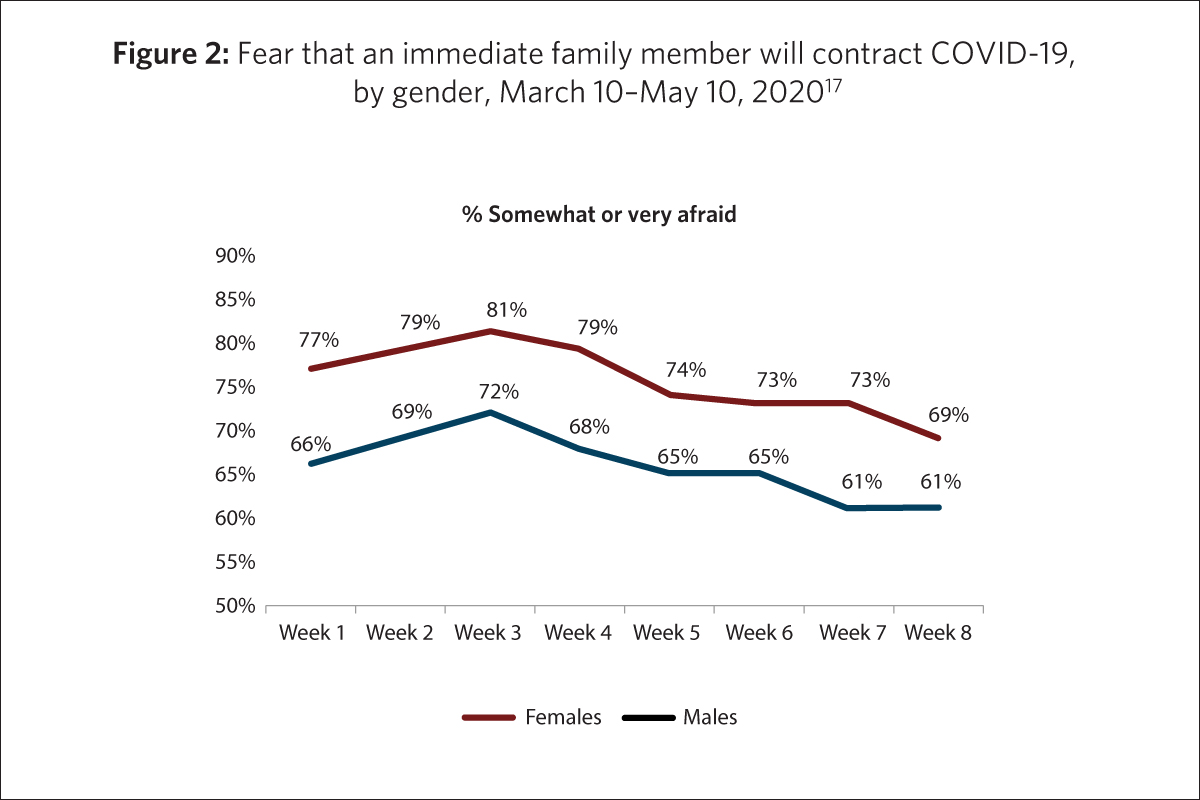

- Regardless of age group or week surveyed, women expressed being more afraid than men that they would contract the virus or that someone in their immediate family would contract it (Fig. 2).16

- Canadians were more afraid of a loved one contracting COVID-19 than they were of contracting it themselves. Adults who were “very” or “extremely”concerned about:

- their own health: 36%

- health of someone in household: 54%

- health of vulnerable people: 79%

- overloading the health care system: 84%18, 19

- More than 4 in 10 of adults living with children under the age of 18 in their home said they “very often” or “often” have had difficulty sleeping since the beginning of the pandemic.20

- When asked to describe how they have been primarily feeling in recent weeks, Canadians were most likely to say they were worried (44%), anxious (41%) and bored (30%); fully one-third (34%) also said they were “grateful.”21

- Women were considerably more likely than men to report experiencing anxiety or nervousness, sadness, irritability or difficulty sleeping during the pandemic.22

- Adults across all age groups continued to exercise during the pandemic, as two-thirds of adults aged 18–34 reported that they were exercising equally as often or more often during the pandemic than they were before it started. The figures were similar for adults aged 35–54 (62%) and aged 55 and older (65%).23

- Younger adults (aged 15–49) were more likely to report an increase in junk food consumption than older adults.24

- Food banks saw a 20% average increase in demand, with some local food banks, such as those in Toronto, Ontario, seeing increases as high as 50%.25

- More than 9 in 10 people aged 15 and older said that the pandemic had not changed their consumption of tobacco nor cannabis.26 Just under 8 in 10 reported that the pandemic had not affected their drinking habits.27

Youth Experiences

- Youth aged 12–19 said they got most of their information about COVID-19 and public health measures from their parents.28

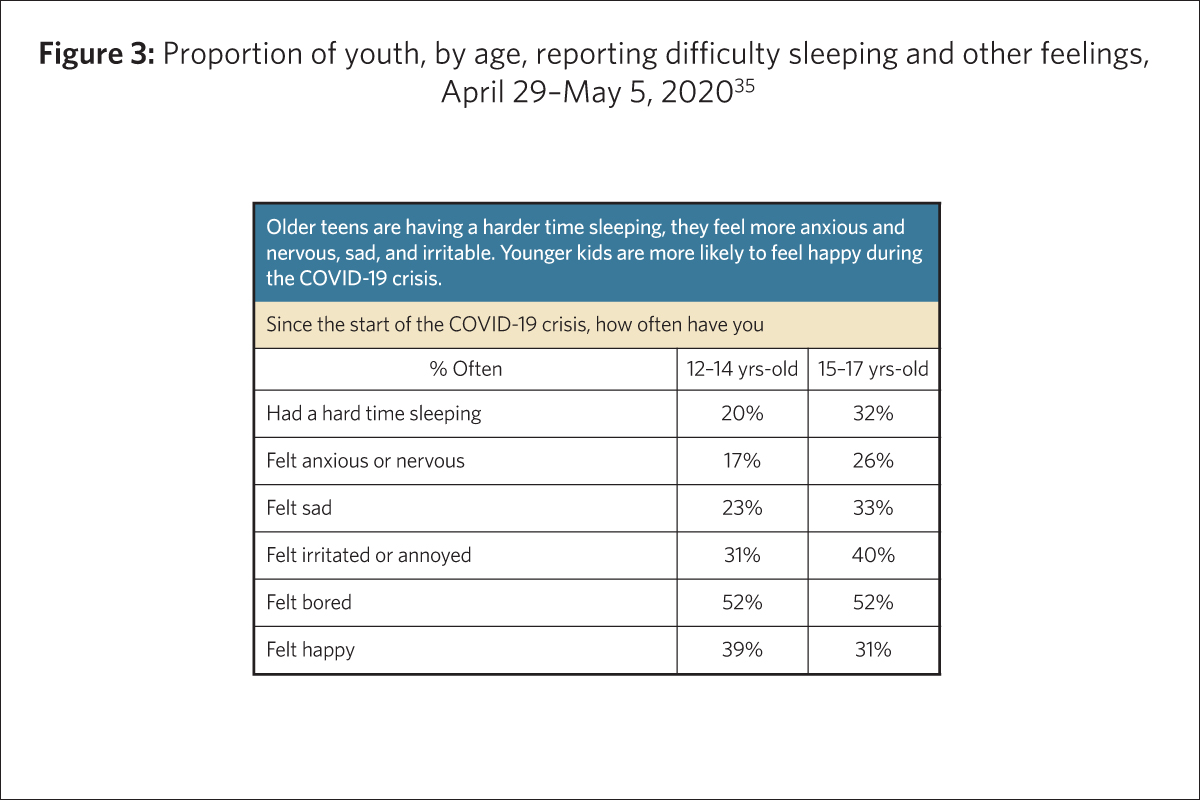

- Older youth, aged 15–17, were more anxious than younger youth, aged 12–14.29

- Among youth aged 15–17, 50% reported that the pandemic had had “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their mental health, compared with 34% of youth aged 12–14. Approximately 4 in 10 youth aged 12–17 reported “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their physical health.30

- Approximately half of children and youth across all age groups missed their friends the most while in isolation.31

- Though 75% of youth claimed to be keeping up with school while in isolation, many were also unmotivated (60%) and disliked the arrangement (57%) (i.e. online learning; virtual classrooms).32

- Many youth said they were doing more housework or chores during the pandemic.33

- Older teens (aged 15–17) were having more difficult sleeping, feeling more anxious or nervous, sad and irritable. Younger teens (aged 12–14) were more likely to feel happy than older teens (Fig. 3).34

COVID-19 Pandemic Response in Canada

Since March 2020, the provincial, territorial and federal governments have announced diverse benefits, credits, programs, initiatives and funds to support families across Canada. The purpose of these recent resources is to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families during this period of uncertainty, including the following:

Temporary Increase to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB)

The Canada Child Benefit (CCB) is a tax-free monthly payment made to eligible families to help with the cost of raising children under the age of 18. The amount of the benefit varies depending on the number of children, the age of the children, marital status and family net income from the previous year’s tax return. The CCB may include the child disability benefit and any related provincial and territorial programs.36

For families already receiving the CCB, an additional $300 per child was added to the benefit in May 2020. For example, a family with two children received $600, in addition to their regular monthly CCB payment, which could be up to a maximum of $553.25 per month per child under the age of 6 and $466.83 per month per child aged 6–17.37, 38

Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)

In April 2020, Canada’s federal government established the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to support workers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The CERB provides $2,000 every four weeks to workers who have lost their income as a result of the pandemic. Eligibility includes adults who have lost their job or who are sick, quarantined or taking care of someone who is sick with COVID-19. It applies to wage earners, contract workers and self-employed individuals who are unable to work. The benefit also allows individuals to earn up to $1,000 per month while collecting CERB.39

As a result of school and child care closures across Canada, the CERB is available to working parents who must stay home without pay to care for their children until schools and child care can safely reopen and welcome back children of all ages.

As of early May 2020, more than 7 million Canadians had applied for CERB since its introduction.40

Mortgage Payment Deferral

Homeowners across Canada who are facing financial hardship due to lack of work or decreased income during the pandemic may be eligible for a mortgage payment deferral of up to six months.

The payment deferral is an agreement between individuals and their mortgage lender, which includes a suspension of all mortgage payment for a specified period of time.41

Special Good and Services Tax Credit

The Goods and Services Tax credit is a tax-free quarterly payment that helps individuals and families with low and modest incomes offset all or part of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) or the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) that they pay.42

In April 2020, the federal government provided a one-time special payment in April 2020 to those receiving the Goods and Services Tax credit. The average additional benefit was nearly $400 for single individuals and close to $600 for couples.43

Temporary wage top-up for low-income essential workers

The federal government is providing $3 billion to increase the wages of low-income essential workers. Examples of essential workers (though variable by province or territory) may include health care professionals, long-term care facility employees and grocery store employees.

Each province or territory is responsible for determining which workers are eligible for this support and how much they will receive.44

Emergency Relief Support Fund for Parents of Children with Special Needs (Province of British Columbia)

To support parents of children with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of British Columbia created a new Emergency Relief Support Fund. The fund will provide a direct payment of $225 per month to eligible families from April to June 2020 (three months).

The payment may be used to purchase supports that help alleviate stress, such as meal preparation and grocery shopping assistance; homemaking services; caregiver relief support and/or counselling services, online or by phone.45

COVID-19 Income Support Program (Province of Prince Edward Island)

In April 2020, the Government of Prince Edward Island announced financial support for individuals whose income has been impacted as a direct result of the public health state of emergency, as well as additional protocols to keep residents safe.

The COVID-19 Income Support Program will help individuals bridge the gap between their loss of income and Employment Insurance (EI) benefits or the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) by providing a one-time, taxable payment of $750.46

Support for Families Initiative (Province of Ontario)

In April 2020, the Government of Ontario announced direct financial support to parents while Ontario schools and child care centres remain closed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new Support for Families initiative offers a one-time payment of $200 per child aged 0–12 and $250 for those aged 0–21 with special needs.47

Emergency Allowance for Income Assistance Clients (Northwest Territories)

For Income Assistance clients registered in March 2020, the Government of the Northwest Territories provided a one-time emergency allowance to help with a 14-day supply of food and cleaning products as the stores have them available.

The Income Assistance (IA) program is designed for residents who are aged 19 and older and who have a need greater than their income. The emergency allowance received by individuals was $500 and for families it was $1,000.48

Parenting in Canada: Government Priorities, Policies, Programs and Resources

The Government of Canada and the provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments provide support to parents in Canada in myriad ways. In addition to the supports provided to assist families during the COVID-19 pandemic, as described in the previous section, a selection of current priorities, policies, programs and resources that are current and existed pre-pandemic are highlighted below.

Early Learning and Child Care

Early learning and child care needs across Canada are vast and diverse. The Government of Canada is investing in early learning and child care to ensure children get the best start in life. As a first step, the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers responsible for early learning and child care have agreed to a Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. The new Framework sets the foundation for governments to work toward a shared long-term vision where all children across Canada can experience the enriching environment of quality early learning and child care. The guiding principles of the Framework are to increase quality, accessibility, affordability, flexibility and inclusivity. A distinct Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework was co-developed with Indigenous partners, reflecting the unique cultures and needs of First Nation, Inuit and Métis children across Canada.49, 50

Before- and After-school Care

Canada’s federal government priorities currently include working with the provinces and territories to invest in the creation of up to 250,000 additional before- and after-school spaces for children under the age of 10, at least 10% of which would allow for care during extended hours. Priorities also include decreasing child care fees for before- and after-school programs by 10%.51

Just for You – Parents

“Just for You – Parents” is a federally created web-based list of resources for parents on topics, including alcohol, smoking and drugs; child abuse; childhood diseases and illnesses; educational resources; family issues; healthy living; mental health; parenting tips (childhood development); school health; and work–life balance. Each topic includes a range of subtopics that direct parents through links to the most up-to-date information available in Canada on issues of importance to them and their children.52

Guaranteed Paid Family Leave Program

In 2019, the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development was tasked to work with the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion to improve and integrate the existing Employment Insurance-based system of maternity and parental benefits and work with the province of Quebec on the effective integration with its own parental benefits system.53

- Maternity and Parental Benefits Administered through the Employment Insurance (EI) program in Canada (excluding Quebec), maternity and parental benefits include financial support (i.e. income replacement for eligible workers) to new mothers and parents following the birth or adoption of a child. The number of weeks and amount paid to each parent varies depending on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the government).54 In Quebec, the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) administers the maternity, paternity, parental and adoption benefits. The amount received by parents is also dependent on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the provincial government). In 2019, the average weekly standard parental benefit rate in Canada reached $464.00 per month.55, 56

Modernizing Canada’s Federal Family Laws

On June 21, 2019, Royal Assent was given to amend Canada’s federal family laws related to divorce, parenting and enforcement of family obligations. The first update to family laws in more than 20 years, this initiative will make federal family laws more responsive to the needs of families through changes to the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act, and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act. The majority of the amendments to the Divorce Act will come into force July 1, 2020, while amendments to the other Acts will take place over two years. The legislation has four key objectives: promote the best interests of the child; address family violence; help to reduce child poverty; and make Canada’s family justice system more accessible and efficient.57

Provincial and Territorial Child Protection Legislation and Policy

The federal, provincial and territorial governments of Canada recognize the importance of surveillance in providing evidence about the contexts, risk factors and types of child maltreatment to inform policy, program, service and awareness interventions. Through their child welfare ministries, the provincial and territorial governments are responsible for assisting children in need of protection; they are also the primary source of administrative data and information related to reported child maltreatment. Preventing and addressing child maltreatment is a complex undertaking that involves the engagement of governments at all levels and in various sectors, including social services, policing, justice and health. At the federal level, the Family Violence Initiative brings together multiple departments to prevent and address family violence, including child maltreatment. The Department of Justice is responsible for the Criminal Code, which includes several forms of child abuse. As the Criminal Code currently stands – which has been debated by advocates and parents alike – section 43 legally allows for the use of corporal punishment on children by select individuals as long as does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstances.58, 59

Nobody’s Perfect

Introduced nationally in 1987 and currently owned by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Nobody’s Perfect is a facilitated parenting program for parents of children aged 0–5. The program is designed to meet the needs of parents who are young, single, or socially or geographically isolated, or who have low income or limited formal education, and is offered in communities by facilitators to help support parents and young children. It provides parents of young children with a safe place to build on their parenting skills, an opportunity to learn new skills and concepts, and a place to interact with other parents who have children the same age.60

Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities

The Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) Program is a national community-based early intervention program funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada. AHSUNC focuses on early childhood development for First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their families living off-reserve. Since 1995, AHSUNC has provided funding to Indigenous community-based organizations to develop and deliver programs that promote the healthy development of Indigenous preschool children. It supports the spiritual, emotional, intellectual and physical development of Indigenous children, while supporting their parents and guardians as their primary teachers.61

Parenting in Canada: Pre-Parenthood to Adolescence62

For expectant parents (or those considering parenthood), the months leading up to the birth or adoption of a child can be exciting and overwhelming. There are many things to prepare for – including the unexpected – in advance of the little one’s arrival. Support in Canada often includes regular and free visits with an obstetrician-gynecologist, a midwife or other registered health care professionals to ensure healthy growth and development. Programs and services are also available in communities across Canada to prepare and plan for parenthood.

- 2SITLGBQ+ Family Planning Weekend Intensive This two-day program is structured to explore pathways to parenthood and strategies for achieving one’s vision of kinship and family. Participants are encouraged to ask questions, gather information and build community, while exploring topics such as co-parenting, multi-parent and single parent families, pregnancy, kinship struggles and self-advocacy. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

- Preparing for Parenthood Geared toward parents-to-be, this program offers information about how to remain healthy during pregnancy and what to expect during the early days and weeks of parenthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Mommies & Mamas 2B/Daddies & Papas 2B This 12-week course is geared toward gay/lesbian, bisexual and queer men/women who are considering parenthood. The course includes resources and discussions to explore practical, emotional, social, ethical, financial, medical, legal, political and intersectional issues related to becoming a parent. Topics explored include co-parenting, surrogacy, parenting arrangements, non-biological and adoptive parenting, fertility awareness, pre-natal care options and legal issues. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

Newborns and Infants

Caring for a newborn or infant comes with many triumphs and challenges. For parents, programs and services are offered across the country, many free of charge, including visits with pediatricians and registered health care professionals. Postnatal care services vary across regions and communities, which may include informational supports, home visits from a public health nurse or a lay home visitor, or telephone-based support (e.g. Telehealth) from a public health nurse or midwife.63 Organizations across the country also offer drop-in programs for parents, grandparents and caregivers to support healthy child development and attachment.

- Roots of Empathy At the heart of the program are an infant and parent who visit a local classroom every three weeks over the course of the school year. Along with a trained Roots of Empathy Instructor, students observe the baby’s development and feelings. This program provides opportunities for parents and infants to take part in teaching emotional literacy and empathy to children aged 5–12, while strengthening their own bonds to each other. (Roots of Empathy)

- Parenting My Baby Tailored to new parents to provide opportunities to learn, participate in discussions on various topics related to infancy, child development and parenting, as well as opportunities to meet fellow new parents. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Bellies & Babies This drop-in group is geared toward pregnant women and new parents with babies from birth to one year. The group provides individual and peer support for pregnant women and postnatal mothers and provides resources and support to new parents. Resources include topics such as the importance of early secure attachment, nutrition, breastfeeding, mental health, infant development and parenting. (Sunshine Coast Community Services Society)

- Young Parents Connect This informal support group is geared toward parents and parents-to-be under the age of 26. It provides an opportunity to meet other young parents, ask questions and share concerns. Each session also includes a fun, interactive activity for children and parents together. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

Toddlers and Preschoolers

Programs for toddlers and preschoolers include a variety of activities to engage both children and their parents to support healthy child development and parent–child attachment. Programs may include drop-in activities, such as those offered by the Boys and Girls Club of Canada or through municipal recreation centres. The drop-in program – offering dancing, story time, arts and crafts and much more – provides opportunities for parents, caregivers and grandparents to take part in learning activities to create, explore and play. Drop-ins welcome moms, dads, grandparents and caregivers, while also providing opportunities to meet and connect with others within the community.

- Parenting Skills 0–5 This online parenting class is designed for families experiencing challenges, providing parents with a foundational understanding to raise their children during the first five years. Topics in this class include child development and personality, discipline, sleep and nutrition. Parenting skills classes are also available for parents with children aged 5–13 and 13–18. (BC Council for Families)

- Fathering Tailored to fathers, including new dads, those experiencing separation or divorce, teen dads and Indigenous dads, this series of resources provides information on how to navigate the various stages of childhood while providing practical tips in support of both fathers and their children. (BC Council for Families)

- Dad HERO (Helping Everyone Realize Opportunities) This project consists of an 8-week parenting course (offered in select correctional institutions in Canada) and a Dad Group both inside the facility for incarcerated fathers and in the community for fathers who were previously incarcerated. This project was designed to educate and teach fathers about parenting, child development and growth, and their role in their children’s lives. Dad HERO provides parenting education and support connecting fathers with their children and improve their mental health and well-being. (Canadian Families and Corrections Network)

School-Aged Children

As children begin and progress through the formal education system in Canada, they encounter various people (i.e. peers, educators) and influences (i.e. social media). Programs and services for parents of school-aged children provide practical tips, informative resources and opportunities to meet and engage with fellow parents in their communities.

- Parenting School-Age and Adult Children This resource was created to support newcomer parenting programs and address some of the challenges that newcomer parents and caregivers may have with parenting in Canadian society. The goal of the program is to gain effective communication skills, better understand the Canadian school systems and create a safe space for parents and caregivers to address their questions and concerns relating to children integrating into the wider Canadian society and culture. (CMAS)

- Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting This workshop series promotes non-violent discipline and respects the child as a learner. It is an approach to teaching that helps children succeed, gives them information and supports their growth from infancy to adulthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Newcomer Parent Resource Series Available in 16 languages (e.g. Urdu, Arabic and Russian), this resource series explores various topics of interest tailored to meet the unique needs of immigrant and refugee parents of young children. Topics include Keeping Your Home Language, Guiding Your Child’s Behaviour, Helping Your Child Cope with Stress, Children Learn Through Play, and Listening to and Talking with Your Child. (CMAS)

- Parenting after Separation: Meeting the Challenges This six-week program is geared toward parents who have recently experienced separation from their partner. Parents meet once a week to discuss the challenge associated with parental separation and divorce and learn practical strategies to support their children. (Family Service Toronto)

- Foster Parent Support This program provides direct, outreach-oriented support to foster parents/caregivers and the children/youth in their care. Support workers work directly with the family in their home, in the community or via phone. This program is intended to be flexible in meeting the unique needs of each foster family and can offer a variety of supports, including teaching conflict resolution skills, de-escalation techniques, collaborative problem solving and using strength-based and trauma-informed approaches. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

Adolescents

Parenting a teen can be challenge, especially in the rapidly evolving era of technology. Adolescence can also be a difficult time for teens who may be questioning their identity, their purpose and envisioning their goals for the future. Programs for parents of teens recognize the importance of supporting children through adolescence as they transition into adulthood.

- Parents Together This is an ongoing professionally facilitated education and group support program for parents who are experiencing challenges while parenting a teen. This program helps parents address their feelings (e.g. guilty, isolation) and provides opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge that can help decrease conflict in the home between parents and their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Transceptance This is an ongoing monthly peer support group for parents and caregivers of transgender youth and young adults. The support provides support and education, reduces isolation and stress, and shares information, including strategies for dealing or coping with disclosures. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

- Parenting in the Know This 10-week education and support program to learn more about adolescent development, teen mental health and other common issues that parents experience. Local guest speakers, community resources, practical ideas and connections with others experiencing similar issues help parents feel better equipped to parent their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Families in TRANSition (FIT) This 10-week program is geared toward parents/caregivers of trans- and gender-questioning youth (aged 13–21) who have recently learned of their child’s gender identity. The program provides support to parents/caregivers to gain tools and knowledge to help improve communication and strengthen their relationship with their youth; learn about social, legal and physical transition options; strengthen skills for managing strong emotions; explore societal/cultural/religious beliefs that impact trans youth and their families; build skills to support their youth and family when facing discrimination, transphobia and/or transmisogyny; and promote youth mental health and resilience. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

Looking Ahead

Families are the most adaptive institution in the world. They are resilient, diverse and strong.

As countries around the world begin to focus on the post-pandemic future, families and family experiences will continue to evolve and adapt. Parents may return to work outside the home, when children return to school and child care, and many will continue to work remotely. Some extracurricular activities will return, while classes like martial arts may continue to be delivered online.

While predicting the future has never been easy, the impact and realities of the global pandemic on families is not yet known, and programs and services may require adjustments in order to support the physical, mental, emotional and social well-being of parents and their children through a trauma-informed lens. Though many families may have been safe at home, some experienced an increase in violence, stress, isolation and anxiety.

Policy and program development, benefits, resources, supports and services will require a comprehensive understanding of families in Canada, their experiences and aspirations; thoughts and fears; and hopes and dreams during this period in time which has evolved and may forecast what lies ahead. The research and innovation behind the many initiatives, including those included in this paper, will help guide evidence-informed decisions; the development, design and implementation of evidence-based programs, policies and practices; and evidence-inspired innovation at all levels of government, community organizations, workplaces and faith communities to ensure families in Canada thrive now and into the future.

Nora Spinks is CEO at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Sara MacNaull is Program Director at the Vanier Institute ofthe Family.

Jennifer Kaddatz is a senior analyst at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Published on June 23, 2020

______________________________________________________________________________

This report was originally published on June 23, 2020 on the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA) website as part of the Expert Group Meeting on Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. This event was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of UNDESA to convene diverse experts from around the world virtually to discuss the impact of COVID-19 on families, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Appendix A: Organizational and Program Overview

Founded in 1977, the BC Council for Families (BCCF) has been developing and delivering family support resources and training programs to professionals across the province of British Columbia as a way to share knowledge and build community connections. The BCCF offers online classes, resources and programs to support parents and children from infancy to adulthood.

The Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada offer educational, recreational and skills development programs and services to children and youth in communities across Canada. The Clubs strive to provide safe, supportive places where children and youth can experience new opportunities, overcome barriers, build positive relationships and develop confidence and skills for life. Many Clubs also offer programs and services to parents to support child development and attachment.

__________

Founded in 1992, Canadian Families and Corrections Network (CFCN) aims to build stronger and safer communities by assisting families affected by criminal behaviour, incarceration and reintegration. Their work includes developing resources for children, parents and families to understand the correctional system and process in Canada and to support families as they manage the experience of having a loved one incarcerated.

__________

The Central Toronto Youth Services (CTYS) is a community-based, accredited Children’s Mental Health Centre that serves many of Toronto’s most vulnerable youth. Their programs and services meet a diversity of needs and challenges that young people experience, such as serious mental health issues; conflicts with the law; coping with anger, depression, anxiety, marginalization or rejection; and issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.

__________

Founded in 2000, CMAS focuses on caring for immigrant and refugee children by sharing their expertise with immigrant serving organizations and other organizations in the child care field. They currently identify gaps in service and work to create solutions; establish and measure the standards of care; and support services for newcomer families through resources, training and consultations.

__________

EarlyON Child and Family Centres provide opportunities for children from birth to age 6 to participate in play and inquiry-based programs, and support parents and caregivers in their roles. The goal of the EarlyON is to enhance the quality and consistency of child and family programs across Ontario.

__________

For more than 100 years, Family Service Toronto has been supporting individuals and families through counselling, community development, advocacy and public education programs. This includes direct service work of intervention and prevention such as counselling, peer support and education; knowledge building and exchanging activities; and system-level work, including social action, advocacy, community building and working with partners to strengthen the sector.

__________

Founded in 2001 and housed at the Sherbourne Health Centre (in Toronto, Ontario), the LGBTQ+ Parenting Network supports lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer parenting through resource development, training and community organizing. The Network coordinates a wide range of programs and activities with and on behalf of LGBTQ parents, prospective parents and their families, including newsletters, print resources, support groups, social events, research projects, advocacy and training.

__________

For more than 30 years, Roots of Empathy has strived to build caring, peaceful and civil societies through the development of empathy in children and adults. The goals of Roots of Empathy are to foster the development of empathy; develop emotional literacy; reduce levels of bullying, aggression and violence; promote children’s pro-social behaviours; increase knowledge of human development, learning and infant safety; and prepare students for responsible citizenship and responsive parenting.

__________

Since 1974, Sunshine Coast Community Services Society (SCCSS) has provided services for individuals and families along the Sunshine Coast (British Columbia). Programs are focused around child and family counselling; child development and youth services; community action and engagement; domestic violence; and housing.

Notes

- GBA+ is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ also considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability. Link: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/index-en.html

- Government of Canada. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update” (May 31, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html

- Marc Montgomery, “COVID-19 Deaths: Calls for Government to Take Control of Long Term Care Homes,” Radio-Canada International (May 25, 2020). Link: https://www.rcinet.ca/en/2020/05/25/covid-19-deaths-calls-for-government-to-take-control-of-long-term-care-homes/

- A survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted weekly starting in March (beginning March 10–12), through April and May 2020, included approximately 1,500 individuals aged 18 and older, interviewed using computer-assisted web-interviewing technology in a web-based survey. Some weekly surveys included booster samples of specific populations. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to gender, age, mother tongue, region, education level and presence of children in the household in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (web panel in this case). However, for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,512 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.52%, 19 times out of 20.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19,” The Daily (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200408/dq200408c-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Though data varies, reports have claimed that consultations by the federal government reveal a 20% to 30% increase in violence rates in certain regions which is supported by organizations such as Vancouver’s Battered Women Support Services that has reported a 300% increase in calls related to family violence during the pandemic. Links: https://bit.ly/2OKYsK0, https://bit.ly/2ZOiF8f.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadians’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic” (May 27, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200527/dq200527b-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada’s healthcare system is publicly funded, which means that all Canadian residents have reasonable access to medically necessary hospital and physician services without paying out-of-pocket. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Worry, Gratitude & Boredom: As COVID‑19 Affects Mental, Financial Health, Who Fares Better; Who Is Worse?” (April 27, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-mental-health/

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada, “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19.”

- Beatrice Britneff, “Food Banks’ Demand Surges Amid COVID-19. Now They Worry About Long-Term Pressures,” Global News (April 15, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/3boEHRe.

- On October 17, 2018, the use of cannabis for recreation and medicinal purposes among adults became legal in Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/cannabis/

- Michelle Rotermann, “Canadians Who Report Lower Self-Perceived Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic More Likely to Report Increased Use of Cannabis, Alcohol and Tobacco,” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada (May 7, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.htm.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, in partnership with Experiences Canada and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted a nation-wide COVID-19 web survey of the 12- to 17-year-old population in Canada from April 29 to May 5. A total of 1191 responses were received, and the probabilistic margin of error was ±3%. Link: https://acs-aec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Youth-Survey-Highlights-May-21-2020.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Kids & COVID-19: Canadian Children Are Done with School from Home, Fear Falling Behind, and Miss Their Friends” (May 11, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-kids-opening-schools/

- Ibid.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada Revenue Agency. “Canada Child Benefit” (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan” (May 28, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/economic-response-plan.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada Child Benefit: How Much You Can Get” (January 27, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca

/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview/canada-child-benefit-we-calculate-your-ccb.html - Government of Canada. “Expanding Access to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Proposing a New Wage Boost for Essential Workers” (April 17, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2020/04/expanding-access-to-the-canada-emergency-response-benefit-and-proposing-a-new-wage-boost-for-essential-workers.html.

- Catherine Cullen and Kristen Everson, “Canadians Who Don’t Qualify for CERB Are Getting It Anyway – And Could Face Consequences,” CBC News (May 2, 2020). Link: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/cerb-covid-pandemic-coronavirus-1.5552436

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan.”

- Government of Canada. “GST/HST Credit – Overview” (May 28, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/goods-services-tax-harmonized-sales-tax-gst-hst-credit.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan.”

- Ibid.

- Province of British Columbia. “Province Provides Emergency Fund for Children with Special Needs” (April 8, 2020). Link: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2020CFD0043-000650

- Government of Prince Edward Island. “Province Announces Additional Income Relief, Stricter Screening Measures for Travelers” (April 1, 2020). Link: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/province-announces-additional-income-relief-stricter-screening-measures-travelers

- Government of Ontario. “Ontario Government Supports Families in Response to COVID-19” (April 6, 2020). Link: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/04/ontario-government-supports-families-in-response-to-covid-19.html

- Government of Northwest Territories. “Backgrounder and FAQs | Income Security Programs” (n.d.). Link: https://www.gov.nt.ca/sites/flagship/files/documents/back_grounder_faq_income_assistance_measures_en.pdf

- Employment and Social Development Canada. “Early Learning and Child Care” (August 16, 2019). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/early-learning-child-care.html

- Government of Canada. “Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework” (September 17, 2018). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/indigenous-early-learning/2018-framework.html

- Government of Canada. “Minister of Families, Children and Social Development Mandate Letter” (December 13, 2019). Link: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2019/12/13/minister-families-children-and-social-development-mandate-letter

- Government of Canada. “Just for You – Parents” (April 20, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/healthy-living/just-for-you/parents.html

- Liberal Party of Canada. “Choose Forward: More Time and Money to Help Families Raise Their Kids.”

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. “Maternity and parental leave benefits” (August 17, 2017). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/services/starting-family/maternity-parental-leave-benefits.html

- Government of Québec. “Québec Parental Insurance Plan: What Types of Benefits Are Available to Me?” (May 30, 2017).

- Government of Canada. Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the Fiscal Year Beginning April 1, 2017 and Ending March 31, 2018 (June 1, 2019). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/ei/ei-list/reports/monitoring2018.html

- Department of Justice. “Strengthening and Modernizing Canada’s Family Justice System” (August 29, 2019). Link: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fl-df/cfl-mdf/01.html

- Government of Canada. Provincial and Territorial Child Protection Legislation and Policy – 2018 (May 13, 2019). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/provincial-territorial-child-protection-legislation-policy-2018.html#2

- Kathy Lynn, “The Canadian Debate on Spanking and Violence Against Children,” The Vanier Institute of the Family (November 15, 2016).

- Nobody’s Perfect. Parent Information (n.d.). Link: http://nobodysperfect.ca/parents/parent-information/

- Public Health Agency of Canada. “Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC)” (October 23, 2017). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/aboriginal-head-start-urban-northern-communities-ahsunc.html

- Additional information about the organizations mentioned in this section that deliver programs or services to parents can be found in Appendix A.

- The Vanier Institute of the Family. “In Context: Understanding Maternity Care in Canada” (May 11, 2017).

Parents’ Thoughts on Post-Pandemic Future in Canada

Nadine Badets

May 6, 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic restrictions have transformed family life in Canada. With the closure of schools, daycares, restaurants and many businesses, as well as major job losses and new work-from-home measures, many parents and children are spending a lot more time together.

So how do families feel about life after the pandemic? Six weeks of data from the Vanier Institute of the Family, the Association for Canadian Studies and Leger show that families with children are not ready to send them back to school this year, but parents are ready to go back to their workplaces after the pandemic, among other findings from this ongoing series of surveys.1

Fear of coronavirus greater among families caring for children

As of May 6, 2020, children and youth 19 years and younger represent a small portion of COVID-19 cases in Canada (5%).2 Nevertheless, almost 30% of adults living with children and youth under 18 are very afraid that someone in their immediate family will contract COVID-19, compared with 22% of people not living with children3 (fig. 1).

Even so, more than half of adults living with children (56%) said they would support a government policy that relaxes social (physical) distancing restrictions for everyone under 65, whereas 42% of people living without children said they would support this policy.

Most parents don’t want children to attend summer school to catch up

Over 80% of parents are living with their children during the pandemic, and 7% are sharing custody of their children with a parent in a separate household. Six in 10 parents (60%) reported they are now talking to their children more often than before the lockdown. Parents of school-aged children are also navigating the education system with their children as newly instated teachers, tutors and homework helpers. Home schooling is challenging for many families,4 raising concerns about students falling behind.

Most provinces have not yet announced plans to reopen schools, whereas all three territories have confirmed they will keep schools closed until September. However, Quebec has pledged to reopen most elementary schools on May 11 and, as of April 29, 2020, Ontario and Nova Scotia have tentative opening dates closer to June, but their deadlines keep shifting.5 When surveyed, two-thirds (66%) of parents indicate that even if schools in Canada open before the end of June, they would prefer for their children to return to school in September, rather than attend school over the summer (July and/or August) to catch up for missed time.

More than half of parents are ready to return to work but don’t want to use public transit

The COVID-19 pandemic has created enormous job losses across the country,6 and parents living with children who view the COVID-19 outbreak as a “major threat” to their jobs were more likely to report feeling sad and anxious or nervous, compared with people living without children.7

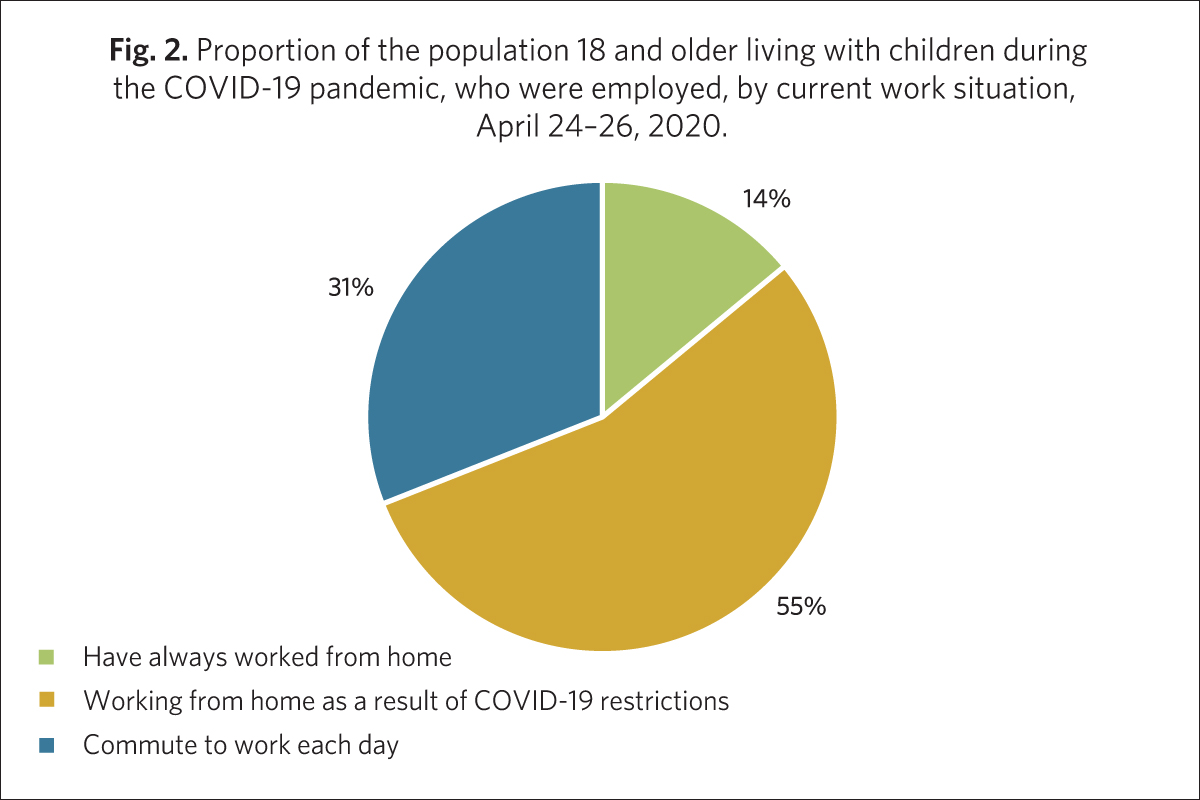

Of those still employed, people living with children were more likely to report satisfaction with the measures their employer put in place to fight COVID-19 (59%) than people without children (37%). This could be because they can work from home and care for their children given that daycares and schools are closed. About 55% of adults living with children reported they are now working from home (fig. 2). People living with children were also more likely to say they would be comfortable returning to their workplace once the COVID-19 restrictions are lifted (54%) than people without children (37%).

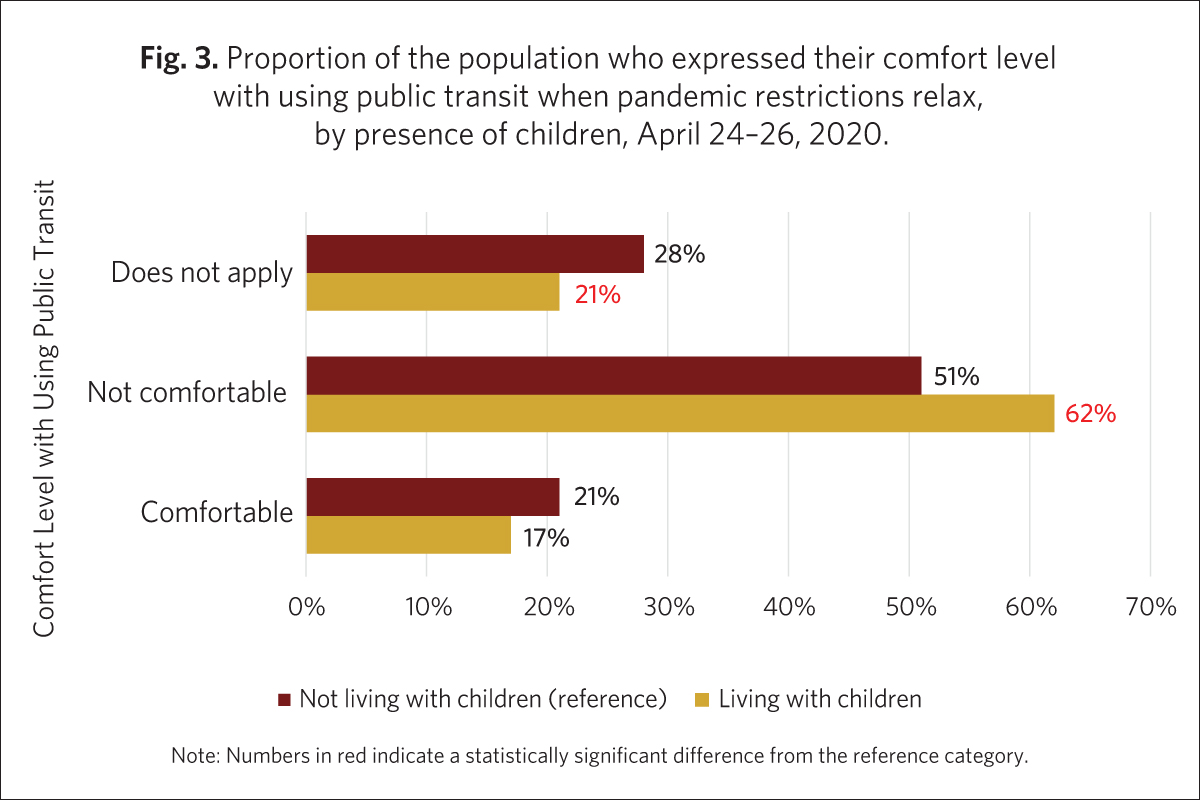

However, more than 60% of parents said they would not be comfortable riding public transit, even when COVID-19 restrictions start being relaxed, which could have implications for commuting once people return to their workplace (fig. 3). Adults living with children were more likely to say they would prefer to commute to work only when needed (39%) than people without children (27%).

Parents abandoning vacation plans, most won’t travel in 2020

In addition to expressing discomfort with commuting in public transit, parents are also not comfortable with travel. About 6 in 10 (59%) adults living with children reported that they had to change vacation plans due to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, which was likely affected by Canada’s lockdown and borders closing around March break. When asked if they now plan to take a vacation during 2020, 72% of parents said it was unlikely.

Nadine Badets, Vanier Institute on secondment from Statistics Canada

Notes