Family Work is the second section of a larger report that also explores family structure, family identity, and family wellbeing.

Topic: Parental leave and benefits

Robin McMillan

Robin McMillan has spent her career of over 30 years working in the early learning sector. For the first eight years, she worked as an Early Childhood Educator with preschool children. She left the front line to develop resources for practitioners at the Canadian Child Care Federation (CCCF). She has been with the CCCF since 1999 and worked her way from Project Assistant to Project Manager to her present role as Innovator of Projects, Programs and Partnerships. Highlights of her career with CCCF have been managing over 20 national and international projects, including a CIDA project in Argentina and presenting a paper with the Honourable Senator Landon Pearson to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva, Switzerland.

Robin served as a board member on the Ottawa Carleton Ultimate Association for two years, as well as participated in organizing numerous local charity events. She founded and facilitated a local parent support group, Ottawa Parents of Children with Apraxia, and a national group, Apraxia Kids Canada. She is married and has a 17-year-old son with a severe speech disorder, childhood apraxia of speech, and a mild intellectual disability, which launched her into the world of parent advocacy. She was the recipient of the Advocate of the Year Award in 2010 from the Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America.

About the Organization: We are the community in the early learning and child care sector in Canada. Professionals and practitioners from coast to coast to coast belong in our community. We give voice to the deep passion, experience, and practice of Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) in Canada. We give space to excellent research in policy and practice to better inform service development and delivery. We provide leadership on issues that impact our sector because we know we are making a difference in the lives of young children—our true purpose, why we exist—to make a difference in these lives. What gets talked about, explored, and shared in our community is always life changing, and we know that. We are a committed, passionate force for positive change where it matters most—with children.

Kim de Laat

Kim de Laat is a sociologist and Assistant Professor of Organization and Human Behaviour at the Stratford School of Interaction Design and Business, University of Waterloo. Her research explores the temporal and spatial dimensions of work—in terms of how much one works, and where work is accomplished—and how these relate to racial and gender inequalities. Kim has two ongoing research projects. The first examines how parents working in creative careers navigate the demands of child care alongside their creative practice. Second, she is exploring how flexible work arrangements, such as hybrid and remote work, influence the allocation of work—both paid work at the office, and unpaid housework and child care in the home.

Donna S. Lero

Donna S. Lero is University Professor Emerita and the inaugural Jarislowsky Chair in Families and Work at the University of Guelph, where she co-founded the Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being. Donna does research in Social Policy, Work and Family, and Caregiving. Her current projects focus on maternal employment and child care arrangements, parental leave policy, and disability and employment, as well as the Inclusive Early Childhood Service System (IECSS) project and the SSHRC project Reimagining Care/Work Policies.

Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay

Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay is professor of labour economics/sociology and human resources management at TÉLUQ University (Université du Québec). She was appointed Canada Research Chair on the socio-economic challenges of the Knowledge Economy in 2002 and director of a CURA (Community-University Research Alliance) on the management of social times and work-life balance in 2009 (www.teluq.ca/aruc-gats). She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and of the Centre of Excellence of the Université du Québec, in recognition of the quality of her research and publications. She works on work-life issues, work organization (telework, coworking), and working time arrangements. Diane-Gabrielle has published many books, including a Labour Economics textbook, a Sociology of Work textbook, three books on working time and work-life issues and she has published in various international journals.

Lindsey McKay

Lindsey McKay is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia. She is a feminist sociologist/political economist of care work, health and medicine, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Social justice motivates her research and teaching. She has published in peer-reviewed journals and public platforms on parental leave inequity, organ donation, and curriculum and pedagogy. She is a Co-Investigator in the SSHRC funded Reimagining Care/Work Policies project with a focus on parental leave.

Research Snapshot: Maternal Labour Force Participation and Separation Anxiety Among Children

Findings from a study about working mothers and separation anxiety among children

Father’s Day 2023: Changing Roles, Changing Profiles

A roundup of stats about dads in Canada in advance of Father’s Day 2023

Three Takeaways from the Quebec Childcare Model

Lessons from Quebec’s childcare system for other provinces and territories in Canada

Policy Brief: Access to Parental Benefits in Canada

A 50-year review of access to parental benefits in Canada

Child Care Policy in Canada: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Gordon Cleveland reflects on progress in child care policy and next steps.

Paternity Benefit Use During COVID-19: Early Findings from Quebec

Sophie Mathieu, PhD, and Marie Gendron, CEO of the Conseil de gestion de l’assurance parentale, share recent findings on paternity leave uptake during pandemic in Quebec.

Researcher Spotlight: Kim de Laat

Kim de Laat discusses her research on family diversities, inequality and parental leave.

Stories Behind the Stats: Becoming a New Dad During Lockdown

A conversation with a new dad about his journey into fatherhood during lockdown.

Research Recap: Positive Impacts of Parental Benefits on Couple Relationships

Nathan Battams and Gaby Novoa highlight findings from a study on parental leave and divorce.

Report: COVID-19 and Parenting in Canada

September 3, 2020

In June 2020, the Vanier Institute prepared the report Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada for the UN Expert Group Meeting Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. Now available in English and French, this report highlights family experiences, connections and well-being during COVID-19, as well as the current resources, policies, programs and initiatives in place to support families and family life.

Families “Safe at Home” details federal, provincial and territorial resources created to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families. In addition to government responses, a summary is provided of the diverse range of available services that support families from pre-parenthood to adolescence and that serve parents across Canada, including those who belong to Indigenous, 2SITLGBQ+ and newcomer communities.

The Expert Group Meeting was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA), where experts from diverse fields from around the world connected virtually to discuss COVID-19 impacts, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada

Nora Spinks, Sara MacNaull, Jennifer Kaddatz

Toward the end of 2019, news began to spread around the world about the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Like many other countries, Canada was facing the possibility of weeks and months with families living in isolation in their homes, changes to school and work schedules, and unknown impacts on family connections and well-being.

In 2020, global citizens around the world are living in and adapting to new ways of life while remaining “safe at home” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadians have been striving to respect physical and social distancing guidelines implemented by our governments and based on the recommendations of public health officials since March 10, 2020. For many families, the past three months have included parenting in close quarters with high levels of uncertainty and unpredictability while managing work commitments, fulfilling care responsibilities inside and outside the home, and homeschooling children of all ages. Despite the inability to plan and the unknowns about what the next few weeks and months might look like, most families are maintaining good physical and mental health, taking care of one another and weathering the storm with their neighbours and communities at a distance.

During these unprecedented times, the Vanier Institute of the Family has adjusted its focus to understanding families in Canada in a time of drastic social, economic and environmental change. The daily activities of individuals and families in Canada, what they are thinking, how they are feeling and what they are doing are all important factors to be addressed and understood in the short, medium or long term.

Accordingly, representatives from the Vanier Institute were co-founders of the COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, a multidisciplinary group of some of Canada’s leading experts along with some of their international colleagues. The network has identified important issues, key indicators and relevant socio-demographics to generate evidence-based responses addressing the social and economic dimensions of the COVID-19 crisis in Canada. As well, to understand the experiences of families during the pandemic, the Vanier Institute has internally mobilized knowledge from other available sources, including quantitative data from both government and non-governmental agencies, such as Statistics Canada and UNICEF Canada, as well as qualitative information from individuals, families and organizations across the nation. Analyses of these findings illuminate characteristics of family life both before and during the pandemic, providing insight into what Canadians fear and what they look forward to after public health measures are lifted.

Consistent with its core principles, the Vanier Institute honours and respects the perspectives of diverse families by applying a family lens and Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+), whenever possible.1 By examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and any of its associated “costs and consequences,” including fertility patterns, parenting, family relationships, family dynamics and family well-being, the Institute mobilizes knowledge to those who study, serve and support families to make sound evidence-based decisions when designing and implementing policies and programs for all families in Canada.

COVID-19 Pandemic Experience in Canada

As of May 31, 2020, 1.6 million people have been tested for COVID-19 in Canada (approximately 4.5% of the total population). Among them, 5% have tested positive for the virus, with 8% resulting in death.2 Seniors in long-term care facilities who have died of COVID-19 represent approximately 82% of all deaths linked to the virus.3

Families are like all other “systems” during the pandemic – their strengths and weakness are magnified, amplified and intensified as relationships, interactions and behaviours adapt to changes in routine, habits and experiences. Family connections, family well-being and youth experiences have all been dramatically affected.

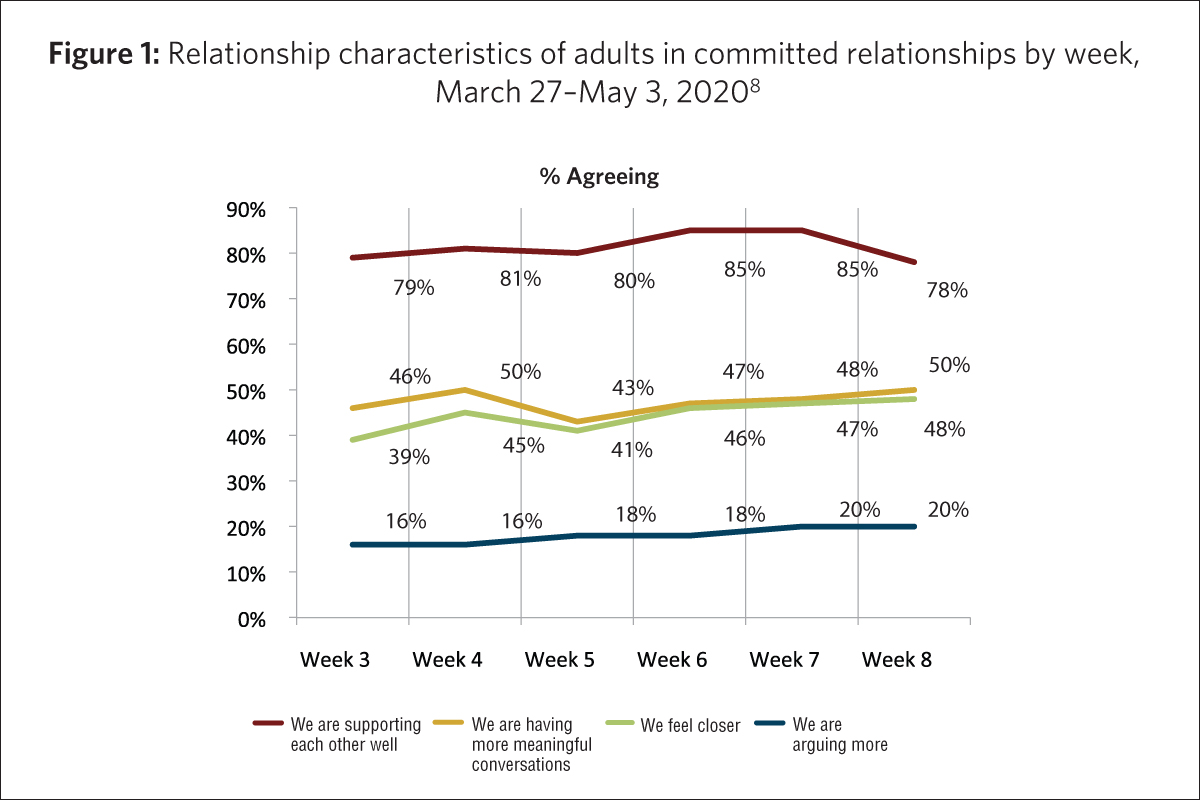

Family Connections

- Approximately 8 in 10 adults (aged 18 and older) who are married or living common-law agreed that they and their spouse were supporting one another well since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1). This figure varies only slightly for those with children or youth at home (77%) compared with those without children under the age of 18 in the household (82%).4

- Fewer than 2 in 10 adults in committed relationships said they had been arguing more since the start of the pandemic (Fig. 1).5

- Six in 10 parents reported they were talking to their children more often than before the lockdown began.6

- When young kids were in the house, adults were almost twice as likely as those with no children or youth at home to have increased their time spent making art, crafts or music.7

On the other hand…

- One-third of adults said that they were very or extremely concerned about family stress from confinement.9

- 10% of women and 6% of men were very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home.10, 11

- About 1 in 5 Canadians had senior relatives living in a nursing home or facility, with 92% of females and 78% of men being very or somewhat concerned for their health.12

Family Well-Being

- More than three-quarters of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants reported either very good or excellent (46%) or good (31%) mental health during pandemic, in a survey conducted April 24–May 11, 2020.13

- Nearly half (48%) of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants said that their mental health was “about the same,” “somewhat better” or “much better” than it had been prior to the start of the pandemic.14

- About half of adults said they felt anxious or nervous or felt sad “very often” or “often” since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis.15

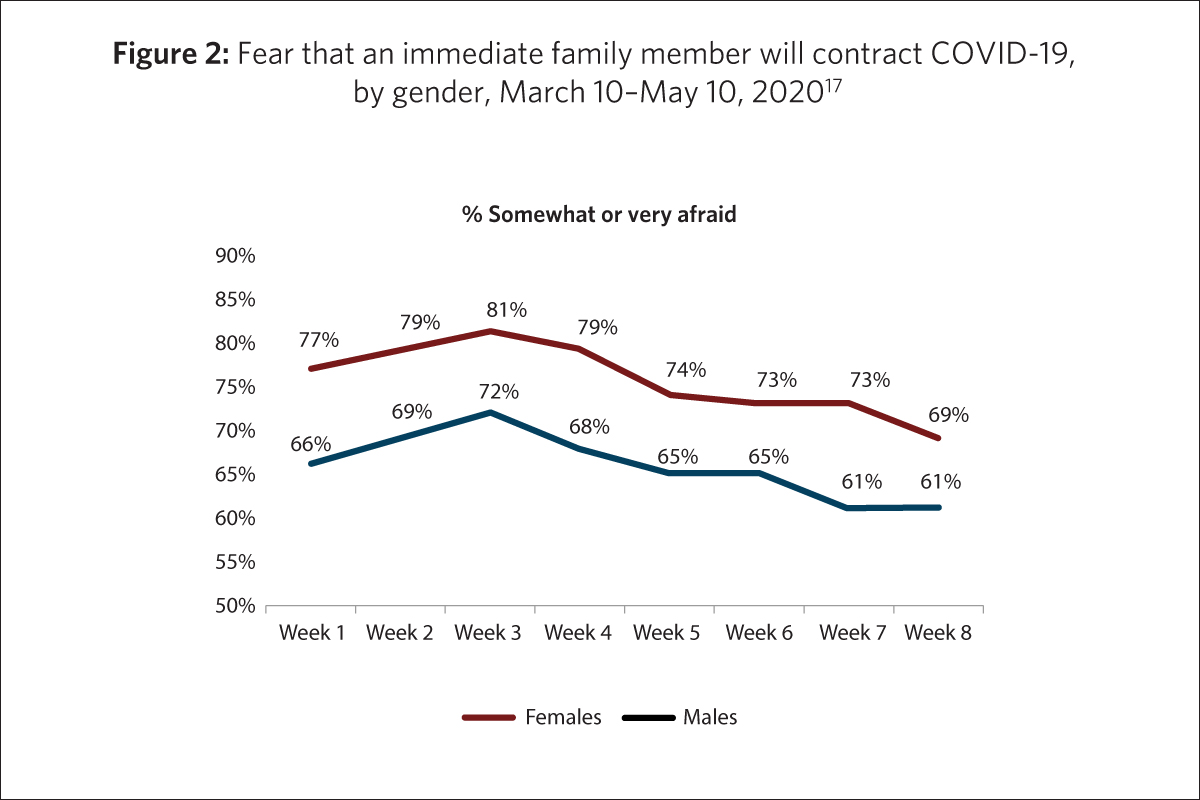

- Regardless of age group or week surveyed, women expressed being more afraid than men that they would contract the virus or that someone in their immediate family would contract it (Fig. 2).16

- Canadians were more afraid of a loved one contracting COVID-19 than they were of contracting it themselves. Adults who were “very” or “extremely”concerned about:

- their own health: 36%

- health of someone in household: 54%

- health of vulnerable people: 79%

- overloading the health care system: 84%18, 19

- More than 4 in 10 of adults living with children under the age of 18 in their home said they “very often” or “often” have had difficulty sleeping since the beginning of the pandemic.20

- When asked to describe how they have been primarily feeling in recent weeks, Canadians were most likely to say they were worried (44%), anxious (41%) and bored (30%); fully one-third (34%) also said they were “grateful.”21

- Women were considerably more likely than men to report experiencing anxiety or nervousness, sadness, irritability or difficulty sleeping during the pandemic.22

- Adults across all age groups continued to exercise during the pandemic, as two-thirds of adults aged 18–34 reported that they were exercising equally as often or more often during the pandemic than they were before it started. The figures were similar for adults aged 35–54 (62%) and aged 55 and older (65%).23

- Younger adults (aged 15–49) were more likely to report an increase in junk food consumption than older adults.24

- Food banks saw a 20% average increase in demand, with some local food banks, such as those in Toronto, Ontario, seeing increases as high as 50%.25

- More than 9 in 10 people aged 15 and older said that the pandemic had not changed their consumption of tobacco nor cannabis.26 Just under 8 in 10 reported that the pandemic had not affected their drinking habits.27

Youth Experiences

- Youth aged 12–19 said they got most of their information about COVID-19 and public health measures from their parents.28

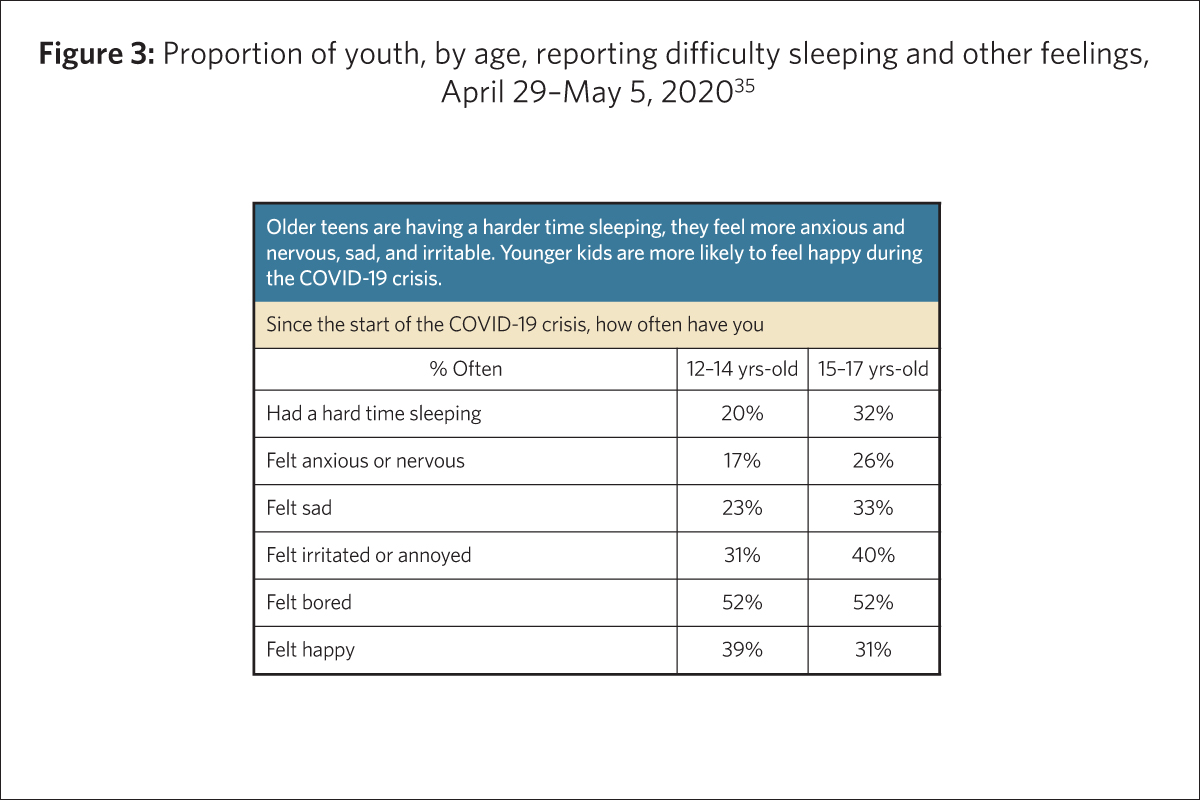

- Older youth, aged 15–17, were more anxious than younger youth, aged 12–14.29

- Among youth aged 15–17, 50% reported that the pandemic had had “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their mental health, compared with 34% of youth aged 12–14. Approximately 4 in 10 youth aged 12–17 reported “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their physical health.30

- Approximately half of children and youth across all age groups missed their friends the most while in isolation.31

- Though 75% of youth claimed to be keeping up with school while in isolation, many were also unmotivated (60%) and disliked the arrangement (57%) (i.e. online learning; virtual classrooms).32

- Many youth said they were doing more housework or chores during the pandemic.33

- Older teens (aged 15–17) were having more difficult sleeping, feeling more anxious or nervous, sad and irritable. Younger teens (aged 12–14) were more likely to feel happy than older teens (Fig. 3).34

COVID-19 Pandemic Response in Canada

Since March 2020, the provincial, territorial and federal governments have announced diverse benefits, credits, programs, initiatives and funds to support families across Canada. The purpose of these recent resources is to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families during this period of uncertainty, including the following:

Temporary Increase to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB)

The Canada Child Benefit (CCB) is a tax-free monthly payment made to eligible families to help with the cost of raising children under the age of 18. The amount of the benefit varies depending on the number of children, the age of the children, marital status and family net income from the previous year’s tax return. The CCB may include the child disability benefit and any related provincial and territorial programs.36

For families already receiving the CCB, an additional $300 per child was added to the benefit in May 2020. For example, a family with two children received $600, in addition to their regular monthly CCB payment, which could be up to a maximum of $553.25 per month per child under the age of 6 and $466.83 per month per child aged 6–17.37, 38

Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)

In April 2020, Canada’s federal government established the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to support workers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The CERB provides $2,000 every four weeks to workers who have lost their income as a result of the pandemic. Eligibility includes adults who have lost their job or who are sick, quarantined or taking care of someone who is sick with COVID-19. It applies to wage earners, contract workers and self-employed individuals who are unable to work. The benefit also allows individuals to earn up to $1,000 per month while collecting CERB.39

As a result of school and child care closures across Canada, the CERB is available to working parents who must stay home without pay to care for their children until schools and child care can safely reopen and welcome back children of all ages.

As of early May 2020, more than 7 million Canadians had applied for CERB since its introduction.40

Mortgage Payment Deferral

Homeowners across Canada who are facing financial hardship due to lack of work or decreased income during the pandemic may be eligible for a mortgage payment deferral of up to six months.

The payment deferral is an agreement between individuals and their mortgage lender, which includes a suspension of all mortgage payment for a specified period of time.41

Special Good and Services Tax Credit

The Goods and Services Tax credit is a tax-free quarterly payment that helps individuals and families with low and modest incomes offset all or part of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) or the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) that they pay.42

In April 2020, the federal government provided a one-time special payment in April 2020 to those receiving the Goods and Services Tax credit. The average additional benefit was nearly $400 for single individuals and close to $600 for couples.43

Temporary wage top-up for low-income essential workers

The federal government is providing $3 billion to increase the wages of low-income essential workers. Examples of essential workers (though variable by province or territory) may include health care professionals, long-term care facility employees and grocery store employees.

Each province or territory is responsible for determining which workers are eligible for this support and how much they will receive.44

Emergency Relief Support Fund for Parents of Children with Special Needs (Province of British Columbia)

To support parents of children with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of British Columbia created a new Emergency Relief Support Fund. The fund will provide a direct payment of $225 per month to eligible families from April to June 2020 (three months).

The payment may be used to purchase supports that help alleviate stress, such as meal preparation and grocery shopping assistance; homemaking services; caregiver relief support and/or counselling services, online or by phone.45

COVID-19 Income Support Program (Province of Prince Edward Island)

In April 2020, the Government of Prince Edward Island announced financial support for individuals whose income has been impacted as a direct result of the public health state of emergency, as well as additional protocols to keep residents safe.

The COVID-19 Income Support Program will help individuals bridge the gap between their loss of income and Employment Insurance (EI) benefits or the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) by providing a one-time, taxable payment of $750.46

Support for Families Initiative (Province of Ontario)

In April 2020, the Government of Ontario announced direct financial support to parents while Ontario schools and child care centres remain closed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new Support for Families initiative offers a one-time payment of $200 per child aged 0–12 and $250 for those aged 0–21 with special needs.47

Emergency Allowance for Income Assistance Clients (Northwest Territories)

For Income Assistance clients registered in March 2020, the Government of the Northwest Territories provided a one-time emergency allowance to help with a 14-day supply of food and cleaning products as the stores have them available.

The Income Assistance (IA) program is designed for residents who are aged 19 and older and who have a need greater than their income. The emergency allowance received by individuals was $500 and for families it was $1,000.48

Parenting in Canada: Government Priorities, Policies, Programs and Resources

The Government of Canada and the provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments provide support to parents in Canada in myriad ways. In addition to the supports provided to assist families during the COVID-19 pandemic, as described in the previous section, a selection of current priorities, policies, programs and resources that are current and existed pre-pandemic are highlighted below.

Early Learning and Child Care

Early learning and child care needs across Canada are vast and diverse. The Government of Canada is investing in early learning and child care to ensure children get the best start in life. As a first step, the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers responsible for early learning and child care have agreed to a Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. The new Framework sets the foundation for governments to work toward a shared long-term vision where all children across Canada can experience the enriching environment of quality early learning and child care. The guiding principles of the Framework are to increase quality, accessibility, affordability, flexibility and inclusivity. A distinct Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework was co-developed with Indigenous partners, reflecting the unique cultures and needs of First Nation, Inuit and Métis children across Canada.49, 50

Before- and After-school Care

Canada’s federal government priorities currently include working with the provinces and territories to invest in the creation of up to 250,000 additional before- and after-school spaces for children under the age of 10, at least 10% of which would allow for care during extended hours. Priorities also include decreasing child care fees for before- and after-school programs by 10%.51

Just for You – Parents

“Just for You – Parents” is a federally created web-based list of resources for parents on topics, including alcohol, smoking and drugs; child abuse; childhood diseases and illnesses; educational resources; family issues; healthy living; mental health; parenting tips (childhood development); school health; and work–life balance. Each topic includes a range of subtopics that direct parents through links to the most up-to-date information available in Canada on issues of importance to them and their children.52

Guaranteed Paid Family Leave Program

In 2019, the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development was tasked to work with the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion to improve and integrate the existing Employment Insurance-based system of maternity and parental benefits and work with the province of Quebec on the effective integration with its own parental benefits system.53

- Maternity and Parental Benefits Administered through the Employment Insurance (EI) program in Canada (excluding Quebec), maternity and parental benefits include financial support (i.e. income replacement for eligible workers) to new mothers and parents following the birth or adoption of a child. The number of weeks and amount paid to each parent varies depending on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the government).54 In Quebec, the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) administers the maternity, paternity, parental and adoption benefits. The amount received by parents is also dependent on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the provincial government). In 2019, the average weekly standard parental benefit rate in Canada reached $464.00 per month.55, 56

Modernizing Canada’s Federal Family Laws

On June 21, 2019, Royal Assent was given to amend Canada’s federal family laws related to divorce, parenting and enforcement of family obligations. The first update to family laws in more than 20 years, this initiative will make federal family laws more responsive to the needs of families through changes to the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act, and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act. The majority of the amendments to the Divorce Act will come into force July 1, 2020, while amendments to the other Acts will take place over two years. The legislation has four key objectives: promote the best interests of the child; address family violence; help to reduce child poverty; and make Canada’s family justice system more accessible and efficient.57

Provincial and Territorial Child Protection Legislation and Policy

The federal, provincial and territorial governments of Canada recognize the importance of surveillance in providing evidence about the contexts, risk factors and types of child maltreatment to inform policy, program, service and awareness interventions. Through their child welfare ministries, the provincial and territorial governments are responsible for assisting children in need of protection; they are also the primary source of administrative data and information related to reported child maltreatment. Preventing and addressing child maltreatment is a complex undertaking that involves the engagement of governments at all levels and in various sectors, including social services, policing, justice and health. At the federal level, the Family Violence Initiative brings together multiple departments to prevent and address family violence, including child maltreatment. The Department of Justice is responsible for the Criminal Code, which includes several forms of child abuse. As the Criminal Code currently stands – which has been debated by advocates and parents alike – section 43 legally allows for the use of corporal punishment on children by select individuals as long as does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstances.58, 59

Nobody’s Perfect

Introduced nationally in 1987 and currently owned by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Nobody’s Perfect is a facilitated parenting program for parents of children aged 0–5. The program is designed to meet the needs of parents who are young, single, or socially or geographically isolated, or who have low income or limited formal education, and is offered in communities by facilitators to help support parents and young children. It provides parents of young children with a safe place to build on their parenting skills, an opportunity to learn new skills and concepts, and a place to interact with other parents who have children the same age.60

Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities

The Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) Program is a national community-based early intervention program funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada. AHSUNC focuses on early childhood development for First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their families living off-reserve. Since 1995, AHSUNC has provided funding to Indigenous community-based organizations to develop and deliver programs that promote the healthy development of Indigenous preschool children. It supports the spiritual, emotional, intellectual and physical development of Indigenous children, while supporting their parents and guardians as their primary teachers.61

Parenting in Canada: Pre-Parenthood to Adolescence62

For expectant parents (or those considering parenthood), the months leading up to the birth or adoption of a child can be exciting and overwhelming. There are many things to prepare for – including the unexpected – in advance of the little one’s arrival. Support in Canada often includes regular and free visits with an obstetrician-gynecologist, a midwife or other registered health care professionals to ensure healthy growth and development. Programs and services are also available in communities across Canada to prepare and plan for parenthood.

- 2SITLGBQ+ Family Planning Weekend Intensive This two-day program is structured to explore pathways to parenthood and strategies for achieving one’s vision of kinship and family. Participants are encouraged to ask questions, gather information and build community, while exploring topics such as co-parenting, multi-parent and single parent families, pregnancy, kinship struggles and self-advocacy. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

- Preparing for Parenthood Geared toward parents-to-be, this program offers information about how to remain healthy during pregnancy and what to expect during the early days and weeks of parenthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Mommies & Mamas 2B/Daddies & Papas 2B This 12-week course is geared toward gay/lesbian, bisexual and queer men/women who are considering parenthood. The course includes resources and discussions to explore practical, emotional, social, ethical, financial, medical, legal, political and intersectional issues related to becoming a parent. Topics explored include co-parenting, surrogacy, parenting arrangements, non-biological and adoptive parenting, fertility awareness, pre-natal care options and legal issues. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

Newborns and Infants

Caring for a newborn or infant comes with many triumphs and challenges. For parents, programs and services are offered across the country, many free of charge, including visits with pediatricians and registered health care professionals. Postnatal care services vary across regions and communities, which may include informational supports, home visits from a public health nurse or a lay home visitor, or telephone-based support (e.g. Telehealth) from a public health nurse or midwife.63 Organizations across the country also offer drop-in programs for parents, grandparents and caregivers to support healthy child development and attachment.

- Roots of Empathy At the heart of the program are an infant and parent who visit a local classroom every three weeks over the course of the school year. Along with a trained Roots of Empathy Instructor, students observe the baby’s development and feelings. This program provides opportunities for parents and infants to take part in teaching emotional literacy and empathy to children aged 5–12, while strengthening their own bonds to each other. (Roots of Empathy)

- Parenting My Baby Tailored to new parents to provide opportunities to learn, participate in discussions on various topics related to infancy, child development and parenting, as well as opportunities to meet fellow new parents. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Bellies & Babies This drop-in group is geared toward pregnant women and new parents with babies from birth to one year. The group provides individual and peer support for pregnant women and postnatal mothers and provides resources and support to new parents. Resources include topics such as the importance of early secure attachment, nutrition, breastfeeding, mental health, infant development and parenting. (Sunshine Coast Community Services Society)

- Young Parents Connect This informal support group is geared toward parents and parents-to-be under the age of 26. It provides an opportunity to meet other young parents, ask questions and share concerns. Each session also includes a fun, interactive activity for children and parents together. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

Toddlers and Preschoolers

Programs for toddlers and preschoolers include a variety of activities to engage both children and their parents to support healthy child development and parent–child attachment. Programs may include drop-in activities, such as those offered by the Boys and Girls Club of Canada or through municipal recreation centres. The drop-in program – offering dancing, story time, arts and crafts and much more – provides opportunities for parents, caregivers and grandparents to take part in learning activities to create, explore and play. Drop-ins welcome moms, dads, grandparents and caregivers, while also providing opportunities to meet and connect with others within the community.

- Parenting Skills 0–5 This online parenting class is designed for families experiencing challenges, providing parents with a foundational understanding to raise their children during the first five years. Topics in this class include child development and personality, discipline, sleep and nutrition. Parenting skills classes are also available for parents with children aged 5–13 and 13–18. (BC Council for Families)

- Fathering Tailored to fathers, including new dads, those experiencing separation or divorce, teen dads and Indigenous dads, this series of resources provides information on how to navigate the various stages of childhood while providing practical tips in support of both fathers and their children. (BC Council for Families)

- Dad HERO (Helping Everyone Realize Opportunities) This project consists of an 8-week parenting course (offered in select correctional institutions in Canada) and a Dad Group both inside the facility for incarcerated fathers and in the community for fathers who were previously incarcerated. This project was designed to educate and teach fathers about parenting, child development and growth, and their role in their children’s lives. Dad HERO provides parenting education and support connecting fathers with their children and improve their mental health and well-being. (Canadian Families and Corrections Network)

School-Aged Children

As children begin and progress through the formal education system in Canada, they encounter various people (i.e. peers, educators) and influences (i.e. social media). Programs and services for parents of school-aged children provide practical tips, informative resources and opportunities to meet and engage with fellow parents in their communities.

- Parenting School-Age and Adult Children This resource was created to support newcomer parenting programs and address some of the challenges that newcomer parents and caregivers may have with parenting in Canadian society. The goal of the program is to gain effective communication skills, better understand the Canadian school systems and create a safe space for parents and caregivers to address their questions and concerns relating to children integrating into the wider Canadian society and culture. (CMAS)

- Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting This workshop series promotes non-violent discipline and respects the child as a learner. It is an approach to teaching that helps children succeed, gives them information and supports their growth from infancy to adulthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Newcomer Parent Resource Series Available in 16 languages (e.g. Urdu, Arabic and Russian), this resource series explores various topics of interest tailored to meet the unique needs of immigrant and refugee parents of young children. Topics include Keeping Your Home Language, Guiding Your Child’s Behaviour, Helping Your Child Cope with Stress, Children Learn Through Play, and Listening to and Talking with Your Child. (CMAS)

- Parenting after Separation: Meeting the Challenges This six-week program is geared toward parents who have recently experienced separation from their partner. Parents meet once a week to discuss the challenge associated with parental separation and divorce and learn practical strategies to support their children. (Family Service Toronto)

- Foster Parent Support This program provides direct, outreach-oriented support to foster parents/caregivers and the children/youth in their care. Support workers work directly with the family in their home, in the community or via phone. This program is intended to be flexible in meeting the unique needs of each foster family and can offer a variety of supports, including teaching conflict resolution skills, de-escalation techniques, collaborative problem solving and using strength-based and trauma-informed approaches. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

Adolescents

Parenting a teen can be challenge, especially in the rapidly evolving era of technology. Adolescence can also be a difficult time for teens who may be questioning their identity, their purpose and envisioning their goals for the future. Programs for parents of teens recognize the importance of supporting children through adolescence as they transition into adulthood.

- Parents Together This is an ongoing professionally facilitated education and group support program for parents who are experiencing challenges while parenting a teen. This program helps parents address their feelings (e.g. guilty, isolation) and provides opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge that can help decrease conflict in the home between parents and their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Transceptance This is an ongoing monthly peer support group for parents and caregivers of transgender youth and young adults. The support provides support and education, reduces isolation and stress, and shares information, including strategies for dealing or coping with disclosures. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

- Parenting in the Know This 10-week education and support program to learn more about adolescent development, teen mental health and other common issues that parents experience. Local guest speakers, community resources, practical ideas and connections with others experiencing similar issues help parents feel better equipped to parent their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Families in TRANSition (FIT) This 10-week program is geared toward parents/caregivers of trans- and gender-questioning youth (aged 13–21) who have recently learned of their child’s gender identity. The program provides support to parents/caregivers to gain tools and knowledge to help improve communication and strengthen their relationship with their youth; learn about social, legal and physical transition options; strengthen skills for managing strong emotions; explore societal/cultural/religious beliefs that impact trans youth and their families; build skills to support their youth and family when facing discrimination, transphobia and/or transmisogyny; and promote youth mental health and resilience. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

Looking Ahead

Families are the most adaptive institution in the world. They are resilient, diverse and strong.

As countries around the world begin to focus on the post-pandemic future, families and family experiences will continue to evolve and adapt. Parents may return to work outside the home, when children return to school and child care, and many will continue to work remotely. Some extracurricular activities will return, while classes like martial arts may continue to be delivered online.

While predicting the future has never been easy, the impact and realities of the global pandemic on families is not yet known, and programs and services may require adjustments in order to support the physical, mental, emotional and social well-being of parents and their children through a trauma-informed lens. Though many families may have been safe at home, some experienced an increase in violence, stress, isolation and anxiety.

Policy and program development, benefits, resources, supports and services will require a comprehensive understanding of families in Canada, their experiences and aspirations; thoughts and fears; and hopes and dreams during this period in time which has evolved and may forecast what lies ahead. The research and innovation behind the many initiatives, including those included in this paper, will help guide evidence-informed decisions; the development, design and implementation of evidence-based programs, policies and practices; and evidence-inspired innovation at all levels of government, community organizations, workplaces and faith communities to ensure families in Canada thrive now and into the future.

Nora Spinks is CEO at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Sara MacNaull is Program Director at the Vanier Institute ofthe Family.

Jennifer Kaddatz is a senior analyst at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Published on June 23, 2020

______________________________________________________________________________

This report was originally published on June 23, 2020 on the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA) website as part of the Expert Group Meeting on Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. This event was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of UNDESA to convene diverse experts from around the world virtually to discuss the impact of COVID-19 on families, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Appendix A: Organizational and Program Overview

Founded in 1977, the BC Council for Families (BCCF) has been developing and delivering family support resources and training programs to professionals across the province of British Columbia as a way to share knowledge and build community connections. The BCCF offers online classes, resources and programs to support parents and children from infancy to adulthood.

The Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada offer educational, recreational and skills development programs and services to children and youth in communities across Canada. The Clubs strive to provide safe, supportive places where children and youth can experience new opportunities, overcome barriers, build positive relationships and develop confidence and skills for life. Many Clubs also offer programs and services to parents to support child development and attachment.

__________

Founded in 1992, Canadian Families and Corrections Network (CFCN) aims to build stronger and safer communities by assisting families affected by criminal behaviour, incarceration and reintegration. Their work includes developing resources for children, parents and families to understand the correctional system and process in Canada and to support families as they manage the experience of having a loved one incarcerated.

__________

The Central Toronto Youth Services (CTYS) is a community-based, accredited Children’s Mental Health Centre that serves many of Toronto’s most vulnerable youth. Their programs and services meet a diversity of needs and challenges that young people experience, such as serious mental health issues; conflicts with the law; coping with anger, depression, anxiety, marginalization or rejection; and issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.

__________

Founded in 2000, CMAS focuses on caring for immigrant and refugee children by sharing their expertise with immigrant serving organizations and other organizations in the child care field. They currently identify gaps in service and work to create solutions; establish and measure the standards of care; and support services for newcomer families through resources, training and consultations.

__________

EarlyON Child and Family Centres provide opportunities for children from birth to age 6 to participate in play and inquiry-based programs, and support parents and caregivers in their roles. The goal of the EarlyON is to enhance the quality and consistency of child and family programs across Ontario.

__________

For more than 100 years, Family Service Toronto has been supporting individuals and families through counselling, community development, advocacy and public education programs. This includes direct service work of intervention and prevention such as counselling, peer support and education; knowledge building and exchanging activities; and system-level work, including social action, advocacy, community building and working with partners to strengthen the sector.

__________

Founded in 2001 and housed at the Sherbourne Health Centre (in Toronto, Ontario), the LGBTQ+ Parenting Network supports lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer parenting through resource development, training and community organizing. The Network coordinates a wide range of programs and activities with and on behalf of LGBTQ parents, prospective parents and their families, including newsletters, print resources, support groups, social events, research projects, advocacy and training.

__________

For more than 30 years, Roots of Empathy has strived to build caring, peaceful and civil societies through the development of empathy in children and adults. The goals of Roots of Empathy are to foster the development of empathy; develop emotional literacy; reduce levels of bullying, aggression and violence; promote children’s pro-social behaviours; increase knowledge of human development, learning and infant safety; and prepare students for responsible citizenship and responsive parenting.

__________

Since 1974, Sunshine Coast Community Services Society (SCCSS) has provided services for individuals and families along the Sunshine Coast (British Columbia). Programs are focused around child and family counselling; child development and youth services; community action and engagement; domestic violence; and housing.

Notes

- GBA+ is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ also considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability. Link: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/index-en.html

- Government of Canada. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update” (May 31, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html

- Marc Montgomery, “COVID-19 Deaths: Calls for Government to Take Control of Long Term Care Homes,” Radio-Canada International (May 25, 2020). Link: https://www.rcinet.ca/en/2020/05/25/covid-19-deaths-calls-for-government-to-take-control-of-long-term-care-homes/

- A survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted weekly starting in March (beginning March 10–12), through April and May 2020, included approximately 1,500 individuals aged 18 and older, interviewed using computer-assisted web-interviewing technology in a web-based survey. Some weekly surveys included booster samples of specific populations. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to gender, age, mother tongue, region, education level and presence of children in the household in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (web panel in this case). However, for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,512 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.52%, 19 times out of 20.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19,” The Daily (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200408/dq200408c-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Though data varies, reports have claimed that consultations by the federal government reveal a 20% to 30% increase in violence rates in certain regions which is supported by organizations such as Vancouver’s Battered Women Support Services that has reported a 300% increase in calls related to family violence during the pandemic. Links: https://bit.ly/2OKYsK0, https://bit.ly/2ZOiF8f.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadians’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic” (May 27, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200527/dq200527b-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada’s healthcare system is publicly funded, which means that all Canadian residents have reasonable access to medically necessary hospital and physician services without paying out-of-pocket. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Worry, Gratitude & Boredom: As COVID‑19 Affects Mental, Financial Health, Who Fares Better; Who Is Worse?” (April 27, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-mental-health/

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada, “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19.”

- Beatrice Britneff, “Food Banks’ Demand Surges Amid COVID-19. Now They Worry About Long-Term Pressures,” Global News (April 15, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/3boEHRe.

- On October 17, 2018, the use of cannabis for recreation and medicinal purposes among adults became legal in Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/cannabis/

- Michelle Rotermann, “Canadians Who Report Lower Self-Perceived Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic More Likely to Report Increased Use of Cannabis, Alcohol and Tobacco,” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada (May 7, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.htm.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, in partnership with Experiences Canada and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted a nation-wide COVID-19 web survey of the 12- to 17-year-old population in Canada from April 29 to May 5. A total of 1191 responses were received, and the probabilistic margin of error was ±3%. Link: https://acs-aec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Youth-Survey-Highlights-May-21-2020.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Kids & COVID-19: Canadian Children Are Done with School from Home, Fear Falling Behind, and Miss Their Friends” (May 11, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-kids-opening-schools/

- Ibid.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada Revenue Agency. “Canada Child Benefit” (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan” (May 28, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/economic-response-plan.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada Child Benefit: How Much You Can Get” (January 27, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca

/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview/canada-child-benefit-we-calculate-your-ccb.html - Government of Canada. “Expanding Access to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and Proposing a New Wage Boost for Essential Workers” (April 17, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2020/04/expanding-access-to-the-canada-emergency-response-benefit-and-proposing-a-new-wage-boost-for-essential-workers.html.

- Catherine Cullen and Kristen Everson, “Canadians Who Don’t Qualify for CERB Are Getting It Anyway – And Could Face Consequences,” CBC News (May 2, 2020). Link: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/cerb-covid-pandemic-coronavirus-1.5552436

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan.”

- Government of Canada. “GST/HST Credit – Overview” (May 28, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/goods-services-tax-harmonized-sales-tax-gst-hst-credit.html

- Government of Canada. “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan.”

- Ibid.

- Province of British Columbia. “Province Provides Emergency Fund for Children with Special Needs” (April 8, 2020). Link: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2020CFD0043-000650

- Government of Prince Edward Island. “Province Announces Additional Income Relief, Stricter Screening Measures for Travelers” (April 1, 2020). Link: https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/news/province-announces-additional-income-relief-stricter-screening-measures-travelers

- Government of Ontario. “Ontario Government Supports Families in Response to COVID-19” (April 6, 2020). Link: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/04/ontario-government-supports-families-in-response-to-covid-19.html

- Government of Northwest Territories. “Backgrounder and FAQs | Income Security Programs” (n.d.). Link: https://www.gov.nt.ca/sites/flagship/files/documents/back_grounder_faq_income_assistance_measures_en.pdf

- Employment and Social Development Canada. “Early Learning and Child Care” (August 16, 2019). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/early-learning-child-care.html

- Government of Canada. “Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework” (September 17, 2018). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/indigenous-early-learning/2018-framework.html

- Government of Canada. “Minister of Families, Children and Social Development Mandate Letter” (December 13, 2019). Link: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2019/12/13/minister-families-children-and-social-development-mandate-letter

- Government of Canada. “Just for You – Parents” (April 20, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/healthy-living/just-for-you/parents.html

- Liberal Party of Canada. “Choose Forward: More Time and Money to Help Families Raise Their Kids.”

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada. “Maternity and parental leave benefits” (August 17, 2017). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/financial-consumer-agency/services/starting-family/maternity-parental-leave-benefits.html

- Government of Québec. “Québec Parental Insurance Plan: What Types of Benefits Are Available to Me?” (May 30, 2017).

- Government of Canada. Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the Fiscal Year Beginning April 1, 2017 and Ending March 31, 2018 (June 1, 2019). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/ei/ei-list/reports/monitoring2018.html

- Department of Justice. “Strengthening and Modernizing Canada’s Family Justice System” (August 29, 2019). Link: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fl-df/cfl-mdf/01.html

- Government of Canada. Provincial and Territorial Child Protection Legislation and Policy – 2018 (May 13, 2019). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/provincial-territorial-child-protection-legislation-policy-2018.html#2

- Kathy Lynn, “The Canadian Debate on Spanking and Violence Against Children,” The Vanier Institute of the Family (November 15, 2016).

- Nobody’s Perfect. Parent Information (n.d.). Link: http://nobodysperfect.ca/parents/parent-information/

- Public Health Agency of Canada. “Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC)” (October 23, 2017). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/aboriginal-head-start-urban-northern-communities-ahsunc.html

- Additional information about the organizations mentioned in this section that deliver programs or services to parents can be found in Appendix A.

- The Vanier Institute of the Family. “In Context: Understanding Maternity Care in Canada” (May 11, 2017).

In Focus 2019: Fathers “Making It Work”

June 16, 2019 is Father’s Day, a time to recognize and celebrate dads and the diverse contributions they make to family life, workplaces and communities across Canada.

Most fathers are in the paid labour force, and research shows that an increasing share is involved in their children’s early years. As more dads are managing multiple responsibilities at home and at work than in previous generations, workplaces and parental leave policies have evolved to support this growing role in family life.

- According to the 2016 Census, 91% of fathers in couples and 82% of lone fathers in Canada were employed.1

- In 2017, 81% of new and expectant fathers2 inside Quebec received (or were intending to claim) parental benefits, compared with only 12% in the rest of Canada.3, 4

- In 2018, the majority of surveyed fathers reported that they are afraid that taking leave will negatively impact their finances (75%) and/or their relationship with their managers at work (51%).5

- As discussed in the Vanier Institute’s May 14, 2019 webinar on Understanding the Parental Sharing Benefit and the Caregiving Benefits, new and expectant fathers6 in eligible two-parent families have had access to a new use-it-or-lose-it 5- to 8-week employment insurance (EI) parental sharing benefit since March 2019, which they can take at any point following the arrival of their child.7

- A 2015 study found that fathers in Quebec who took leave spent an average half hour more per day at the family home than those outside of Quebec.8

- In 2015, 72% of surveyed fathers of children aged 0 to 4 reported that they spent time providing help or care to children that day. Of the total number of reported hours parents spent on these tasks, 35% of this work was done by fathers (28% in 1986).9

Notes

- Statistics Canada, “Father’s Day… By the Numbers,” The Daily (page last updated June 28, 2017). Link: https://bit.ly/2xkDOui.

- This percentage also includes women second partners in same-sex couples, although they account for a small share of the total.

- The share of spouses or partners claiming benefits is typically higher in Quebec, as the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan includes benefits that apply exclusively to the second parent.

- Statistics Canada, “Employment Insurance Coverage Survey, 2017,” The Daily (November 15, 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/2VaYssA.

- Legerweb, “Dove Men+Care Data Reveals Persistent Paternity Leave Stigmas,” media release (April 23, 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/2vfYno3.

- The benefit is available to all second partners (i.e. women second parents in same-sex couples, in addition to fathers), and includes adoptive parents.

- The transcript, PowerPoint presentation and webinar video stream are available on the Vanier Institute website. Link: http://bit.ly/2WmDl1S.

- Ankita Patnaik, “‘Daddy’s Home!’ Increasing Men’s Use of Paternity Leave,” briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families (April 2, 2015). Link: http://bit.ly/1Igwa0Y.

- Patricia Houle, Martin Turcotte and Michael Wendt, “Changes in Parents’ Participation in Domestic Tasks and Care for Children from 1986 to 2015,” Spotlight on Canadians: Results from the General Social Survey, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 89-652-X (page last updated June 7, 2017). Link: http://bit.ly/2rJ4AZL.

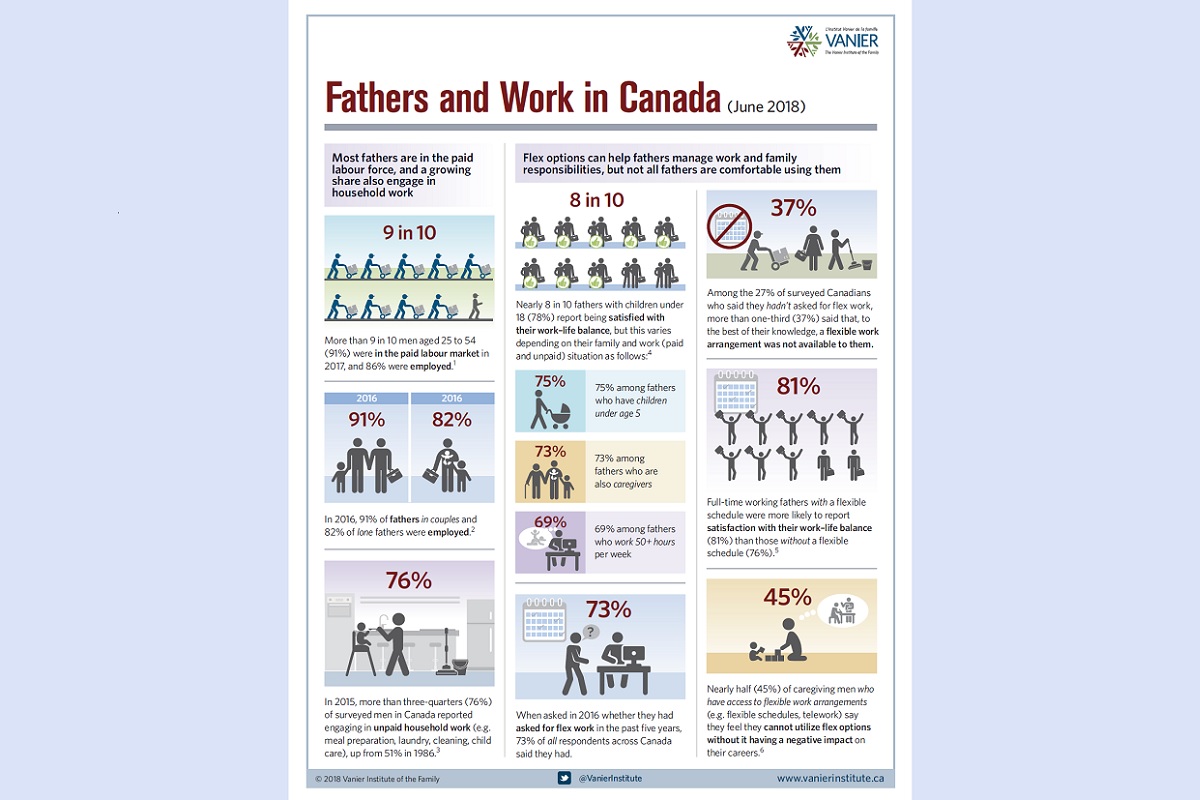

Infographic: Fathers and Work in Canada

Most fathers in Canada are in the paid labour force, and research shows that a growing share are involved in their child’s early years, and are more likely to assume household management responsibilities than in the past. As fathers manage multiple responsibilities at home, at work and in their communities, parental leave and flexible work arrangements can play an important role in facilitating their growing role in family life.

Using current Census and Labour Force Survey data, our new infographic provides a statistical glance at evolving work–family experiences for fathers in Canada.

Highlights include:

- In 2016, 91% of fathers in couples and 82% of lone fathers were employed.1

- In 2016, new and expectant fathers inside Quebec were roughly 6 times as likely to report having received (or were intending to claim) parental benefits than fathers in the rest of Canada (80% and 13%, respectively).2

- As of June 2019, new and expectant fathers in eligible two-parent families3 will have access to a new “use-it-or-lose-it” employment insurance (EI) parental sharing benefit, which they can take at any point following the arrival of their child.4

- In 2016, when asked whether they had asked for flex work in the past five years, 73% of surveyed Canadians said they had.5

- In 2012, full-time working fathers with a flexible schedule were more likely to report satisfaction with their work–life balance (81%) than those without a flexible schedule (76%).6

Download the Fathers and Work in Canada infographic from the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Notes

- Statistics Canada, “Father’s Day… By the Numbers,” The Daily (page last updated June 28, 2017). Link: https://bit.ly/2xkDOui.

- Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the Fiscal Year Beginning April 1, 2016 and Ending March 31, 2017 (page last updated June 5, 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/2LA9WgG.

- Including adoptive and same-sex couples.

- To learn more about pending changes to parental leave, see Canada’s New Parental Sharing Benefit, a backgrounder from the Department of Finance Canada (n.d.). Link: https://bit.ly/2CMmKuX.

- Employment and Social Development Canada, “When Work and Caregiving Collide: How Employers Can Support Their Employees Who Are Caregivers,” Report from the Employer Panel for Caregivers (February 16, 2015). Link: https://bit.ly/2sf0QOv.

- Statistics Canada, “Satisfaction with Work–Life Balance: Fact Sheet,” Spotlight on Canadians: Results from the General Social Survey, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 89-652-X (April 14, 2016). Link: http://bit.ly/1S7H2nb.

Families in Canada Interactive Timeline

Today’s society and today’s families would have been difficult to imagine, let alone understand, a half-century ago. Data shows that families and family life in Canada have become increasingly diverse and complex across generations – a reality highlighted when one looks at broader trends over time.

But even as families evolve, their impact over the years has remained constant. This is due to the many functions and roles they perform for individuals and communities alike – families are, have been and will continue to be the cornerstone of our society, the engine of our economy and at the centre of our hearts.

Learn about the evolution of families in Canada over the past half-century with our Families in Canada Interactive Timeline – a online resource from the Vanier Institute that highlights trends on diverse topics such as motherhood and fatherhood, family relationships, living arrangements, children and seniors, work–life, health and well-being, family care and much more.

View the Families in Canada Interactive Timeline.*

Full topic list:

- Motherhood

o Maternal age

o Fertility

o Labour force participation

o Education

o Stay-at-home moms

- Fatherhood

o Family relationships

o Employment

o Care and unpaid work

o Work–life

- Demographics

o Life expectancy

o Seniors and elders

o Children and youth

o Immigrant families

- Families and Households

o Family structure

o Family finances

o Household size

o Housing

- Health and Well-Being

o Babies and birth

o Health

o Life expectancy

o Death and dying

View all source information for all statistics in Families in Canada Interactive Timeline.

* Note: The timeline is accessible only via desktop computer and does not work on smartphones.

Published February 8, 2018

A Snapshot of Men, Work and Family Relationships in Canada

Over the past half-century, fatherhood in Canada has evolved dramatically as men across the country adapt and react to social, economic, cultural and environmental contexts. Throughout this period, men have had diverse employment experiences as they manage their multiple roles inside and outside the family home. These experiences have been impacted by a variety of factors, including (but not limited to) cultural norms and expectations, family status, disability and a variety of demographic characteristics, as well as women’s increased involvement in the paid labour force.

While many fathers in previous generations acted exclusively as “traditional” breadwinning father figures, modern fathers are increasingly likely to embrace caring roles and assume more household management responsibilities. In doing so, dads across Canada are renegotiating and reshaping the relationship between fatherhood and work.

Highlights include:

- Men are less likely than in previous generations to fulfill a breadwinner role exclusively. In 2014, 79% of single-earner couple families with children included a breadwinning father, down from 96% in 1976.

- Men account for a growing share of part-time workers. One-quarter (25%) of Canadians aged 25 to 54 who worked part-time in 2016 were men, up from 15% in 1986.

- The proportion of never-married men is on the rise. In 2011, more than half (54%) of men in Canada aged 30 to 34 report never having been married, up from 15% in 1981.

- Canada is home to many caregiving men. In 2012, nearly half (46%) of all caregivers in Canada were men, 11% of whom provided 20 or more hours per week of care.

- Many men want to be stay-at-home parents. Nearly four in 10 (39%) surveyed men say they would prefer to be a stay-at-home parent.

- Many men engage in household work and related activities. Nearly half (45%) of surveyed fathers in North America say they’re the “primary grocery shopper” in their household.

- Flex at work can facilitate work–life balance. More than eight in 10 (81%) full-time working fathers who have a flexible schedule say they’re satisfied with their work–life balance, compared with 76% for those without flex.

This bilingual resource will be updated periodically as new data emerges. Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter to find out about updates, as well as other news about publications, projects and initiatives from the Vanier Institute.

A Snapshot of Women, Work and Family in Canada

Canada is home to more than 18 million women (9.8 million of whom are mothers), many of whom fulfill multiple responsibilities at home, at work and in the community. Over many generations, women in Canada have had diverse employment experiences that continue to evolve and change. These experiences have differed significantly from those of men, and there is a great deal of diversity in the experiences among women, which are impacted by a variety of factors including (but not limited to) cultural norms and expectations, family status, disability and a variety of demographic characteristics.

To explore the diverse and evolving work and family experiences of women in Canada, the Vanier Institute of the Family has created A Snapshot of Women, Work and Family in Canada. This publication is a companion piece to our Fifty Years of Women, Work and Family in Canada timeline, providing visually engaging data about the diverse work and family experiences of women across Canada.

Highlights include:

- The share of all core working-aged women (25 to 54 years) who are in the labour force has increased significantly across generations, from 35% in 1964 to 82% in 2016.

- Employment rates vary among different groups of core working-aged women, including those who are recently immigrated (53%), women reporting an Aboriginal identity (67%) and those living with a disability (52% to 56%, depending on the age subgroup).

- On average, women without children earn 12% more per hour than those with children – a wage gap sometimes referred to as the “mommy tax.”

- Nearly one-third (32%) of women aged 25 to 44 who were employed part-time in 2016 said that they were working part-time because they were caring for children.

- 70% of mothers with children aged 5 and under were employed in 2015, compared with only 32% in 1976.

- In 2013, 11% of all recent mothers inside Quebec and 36% in the rest of Canada, respectively, did not receive maternity and/or parental leave benefits – a difference attributed to the various EI eligibility regimes in the provinces.

- 72% of all surveyed mothers in Canada report being satisfied with their work–life balance, but this rate falls to 63% for those who are also caregivers.

- 75% of working mothers with a flexible work schedule report being satisfied with their work–life balance – a rate that falls to 69% for those without flexibility.

This bilingual resource will be updated periodically as new data emerges. Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter to find out about updates, as well as other news about publications, projects and initiatives from the Vanier Institute.

Download A Snapshot of Women, Work and Family in Canada from the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Published on May 9, 2017

Modern Fathers Reshaping the Work–Family Relationship

Nathan Battams

Canada’s “family landscape” is constantly evolving, with social, economic, cultural and environmental forces shaping and redefining family roles and relationships. Fatherhood is no exception, and today’s increasingly diverse 8.6 million dads in Canada are now taking a much greater role in family life than in previous generations.1 Many are moving away from the “traditional” breadwinning father figure to embrace a more caring role and are assuming more household management responsibilities. In doing so, modern dads are renegotiating and reshaping the relationship between fatherhood and work.

Men are “breadwinning” less while more women are taking on more paid work

As the participation of mothers in the paid labour market increased over the past 50 years along with a rise in dual-earner families, the share of “breadwinning dads” has fallen significantly. According to Statistics Canada, in 1976, 36% of families in Canada with at least one child age 16 and under had two earners in the paid labour force. By 2014, this accounted for 69% of these families. Another Statistics Canada study found that, in the same period, the proportion of single-earner families with the father as the sole earner dropped from 51% to only 17%.

Some fathers in couple families are stepping out of the paid labour market altogether to become the lead or primary parent, more commonly known as “stay-at-home” dads, either on a temporary basis while taking care of young children or permanently. Approximately 1% of fathers in single-earner families reported being stay-at-home dads 40 years ago – a rate that has since risen to 11%.

Canada is not alone in this regard. Data from a 2015 report from Pew Research Center suggests a similar trend in the United States, with 7% of US dads with children in the household reporting in 2012 that they “do not work outside the home,” up from 4% in 1989. Among these fathers, the share who said they are staying home to care for family more than quadrupled in this period to 21% (up from 5% in 1989).

Family relationships benefit from dads increasing involvement at home

Alongside these trends, data from the General Social Survey on time use suggests that modern fathers are devoting more time to family. Men report spending more time with family, increasing from 360 minutes per day in 1986 to 379 minutes in 2010. The average number of days fathers of preschool children miss from work for personal or family responsibilities rose from 1.8 days throughout 1997 to 2.0 days in 2015. The gender gap in housework has also been found to have declined in recent generations, with men reporting spending more time on these tasks than 30 years ago.

While only 3% of recent fathers across Canada took time off to receive paid parental leave benefits in 2000, more than one-quarter (27%) reported their intention to do so in 2014. This rate is significantly higher in Quebec (78%), where paternity benefits are offered to new dads in addition to parental benefits under the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP). Quebec is currently the only province to offer paternity benefits, although the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Labour recently expressed interest in setting aside time for dads by making paternity leave a part of the proposed changes to Canada’s parental benefits program.

Greater father involvement can have an impact on family life and family relationships. In a study comparing parental leave in Quebec with the rest of Canada, author Ankita Patnaik found a “large and persistent impact” on gender dynamics in the three-year period following a father’s use of paternity leave. According to her study, fathers who took leave remained more likely to do housework, while mothers were more likely to engage in paid work. Under QPIP, Quebec dads also spent an average half-hour more per day at the family home than those outside of Quebec.

With all this evolution under way across North America, it is perhaps no wonder that many people feel as though their fathers are more involved than in the past. The Pew report mentioned earlier also found that nearly half (46%) of surveyed American fathers say they personally spend more time with their children than their fathers spent with them. In Canada, a Today’s Parent poll found that three-quarters (75%) of surveyed men said that they are more involved with their children than their fathers had been with them.

Children may also be feeling the effect of greater father involvement. According to international HBSC surveys conducted by the World Health Organization in 1993–94 and 2013–14, a growing share of 11-year-old children say they “find it easy” to talk to their fathers about things that really bother them – from 56% to 66% among girls, and from 72% to 75% for boys.

Work–life balance on modern fathers’ minds

As most fathers today are still working while also taking on a greater role in the family home, work–life balance has naturally become a growing part of the discussion about modern fatherhood. Recent data from Statistics Canada shows that most fathers – nearly eight in 10 (78%) – report being satisfied with their work–life balance. Family is central to the “life” in the work–life equation: among parents who said that they were not satisfied, the main cited reason for their dissatisfaction was “not having enough time for family life.”

Through their work–life policies and practices, employers play a significant role in enhancing and supporting the work–life quality of fathers. The same Statistics Canada study found that the share of fathers who report being satisfied with their work–life balance was consistently higher among those who have a flexible schedule (81%, vs. 76% for those without), who can take advantage of a flexible work schedule without a negative impact on their career (83%, vs. 74% for those who cannot), who have the possibility of taking leave without pay to care for their children (79%, vs. 71% for those who do not), and for those who have the possibility of taking leave without pay to provide care to a spouse, partner or other family member (81%, vs. 72% for those who do not).

“The share of fathers who report being satisfied with their work–life balance is higher for those with flexible work environments and with the option to take unpaid leave to care for their children and families.”

What’s good for the family is good for the workplace

Flexibility and work–life balance satisfaction go hand in hand, which means organizations with flexible, family/father-friendly policies are more likely to attract and retain top talent who are (or plan to become) fathers. Conversely, those that do not practise flex may drive away and/or fail to attract dads – in fact, half (49%) of surveyed fathers in Canada said they would consider making a job change if a potential employer offered more family-friendly options than their current employer, according to a Harris/Decima poll.

Modern fathers aren’t caring more, they’re just providing care differently