John-Paul Boyd, M.A., LL.B.

Executive Director

Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family (University of Calgary)

The Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family began a study of perceptions of polyamory in Canada in June 2016. The project is only midway through its course, but the data collected so far have important implications for law and policy in the coming decades, as the meaning of family continues to evolve.

The term polyamory is a mash-up of the Greek word for much or many and the Latin word for love. As these roots suggest, people who are polyamorous are, or prefer to be, involved in more than one intimate relationship at a time. Some polyamorists are involved in stable, long-term, loving relationships involving two or more other people. Others are simultaneously engaged in a number of relationships of varying degrees of permanence and commitment. Still others are involved in a web of concurrent relationships ranging from short-term relationships that are purely sexual in nature to more enduring relationships characterized by deep emotional attachments.

Polyamory

The practice or condition of participating in more than one intimate relationship at a time. It is usually not related to religion and it is unrelated to marriage.

Polygamy

The practice or condition of having more than one spouse, typically a wife, at one time, usually for religious reasons.

Polyamory and polygamy

For many people, TLC’s Sister Wives and the religious community in Bountiful, British Columbia are what come to mind when polyamory is mentioned. However, there are a number of differences between polyamory and the polygamy practised by the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, that being the common connection between Sister Wives and Bountiful. Polygamy in this sense refers to marriages – the “gamy” of polygamy comes from the Greek for marriage – between one man and many wives that are mandated by scripture and distinctly patriarchal.

In contrast, surveyed polyamorists involved in relationships with two or more other adults place a high value on the equality of their partners, regardless of gender or parental status. They tend to believe that their partners should have a say in changes to their relationships and should be able to leave those relationships how and when they wish.

Although Statistics Canada doesn’t track the number of Canadians who are polyamorous or engaged in polyamorous relationships, in just three weeks we received 547 valid responses to a survey on polyamory advertised primarily through social media.1 More than two-thirds of respondents (68%) said that they are currently involved in a polyamorous relationship, and, of those who weren’t, two-fifths (39.9%) said that they had been involved in such a relationship in the last five years. More than four-fifths of respondents said that in their view the number of people who identity as polyamorous is increasing (82.4%), as is the number of people openly involved in polyamorous relationships (80.9%).

If the number of people involved in polyamorous relationships is indeed growing, the potential economic and legal implications are significant, as almost all of Canada’s most important social institutions are predicated on the assumption that adult relationships come only in pairs.

If the number of people involved in polyamorous relationships is indeed growing, the potential economic and legal implications are significant, as almost all of Canada’s most important social institutions are predicated on the assumption that adult relationships come only in pairs. The Canada Pension Plan pays survivor’s benefits to only one spouse; the Old Age Security spousal allowance can only be paid to one partner. The forms we use to calculate our liability to the Canada Revenue Agency likewise assume that taxpayers have sequential but not concurrent relationships, an assumption shared by the provincial legislation on wills and estates and, for the most part, the provincial legislation on domestic relations.

Polyamorists in Canada are generally younger, and live in diverse relationships

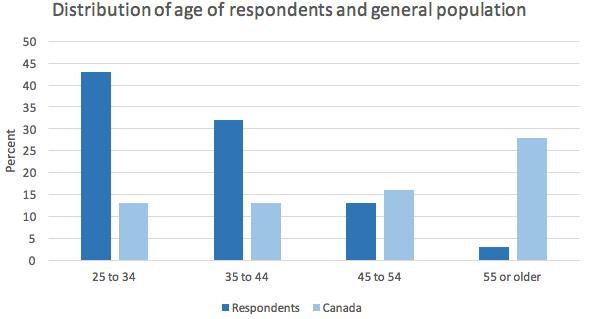

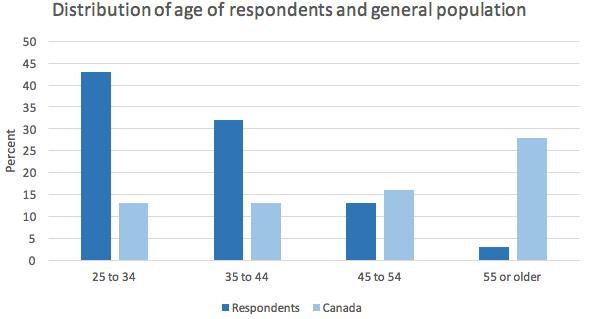

Most of the respondents to our survey live in British Columbia (144), followed by Ontario (116), Alberta (71) and Quebec (37). Respondents tend to be younger than the general Canadian population, with 75% of respondents being between the ages of 25 and 44, compared to 26% of the general population, and only 16% of respondents being age 45 or older, compared to 44% of the general population.

Most of the respondents to our survey had completed high school (96.7%), and respondents’ highest levels of education attained were undergraduate degrees (26.3%), followed by post-graduate or professional degrees (19.2%) and college diplomas (16.3%). Respondents reported achieving significantly higher levels of educational attainment than the general population of Canada: 37% of respondents reported holding an undergraduate university degree, compared with 17% of the general population; and 19% of respondents reported holding a post-graduate or professional degree, compared with 8% of the general population.

The respondents to our survey also tended to have higher incomes than their peers in the general Canadian population. Fewer respondents (46.8%) had incomes under $40,000 per year than the general population (60%), and more respondents (31%) had incomes of $60,000 or more per year than the general population (23%). Although almost half of our respondents had annual incomes of less than $39,999, almost two-thirds of respondents were not the sole income-earner in their household (65.4%) and more than three-fifths of respondents’ households (62.3%) had total incomes between $80,000 and $149,999 per year.

Slightly less than one-third of respondents identified as male (30%) and almost three-fifths identified as female (59.7%); the rest identified as genderqueer (3.5%), gender fluid (3.2%), transgender (1.3%) or “other” (2.2%). A plurality of respondents described their sexuality as either heterosexual (39.1%) or bisexual (31%).

Most of the respondents to our survey described themselves as atheists (33.9%) or agnostic (28.2%). Of those subscribing to an organized faith, most said that they were Christian (non-denominational, 7.2%; Roman Catholic, 3.2%; Protestant, 1.3%). However, more than one-fifth of respondents (22.1%) described their faith as “other,” including Quakers, pagans and polytheists.

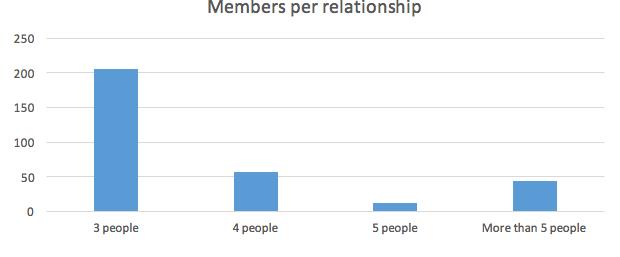

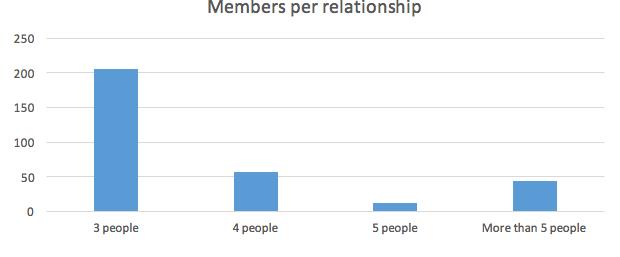

We also asked our respondents about their relationships and living arrangements. Almost two-thirds of the respondents answering this question said that their relationship involved three people (64.6%), 17.9% said that their relationship involved four people and 13.8% said that their relationship involved six or more people. Only one-fifth of respondents said that the members of their relationship lived in a single household (19.7%). Where the members of a family lived in more than one household, most lived in two households (44.3%) or three households (22.2%).

Where the members of a family live in a single household, three-fifths of respondents’ households involved at least one married couple (61.2%), and there was only one married couple in those households. Where the members of a family lived in more than one household, almost half involved at least one married couple (45.4%), and 85% of those households involved one married couple while the remainder involved two married couples (12.9%), three married couples (1.4%) and more than three married couples (0.7%).

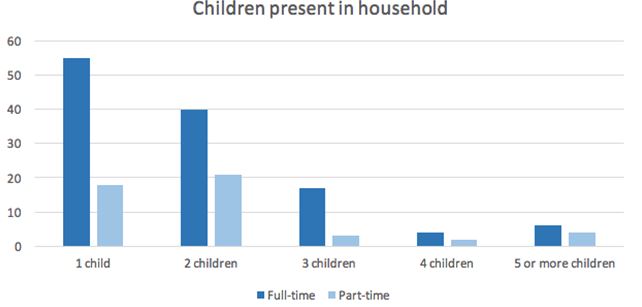

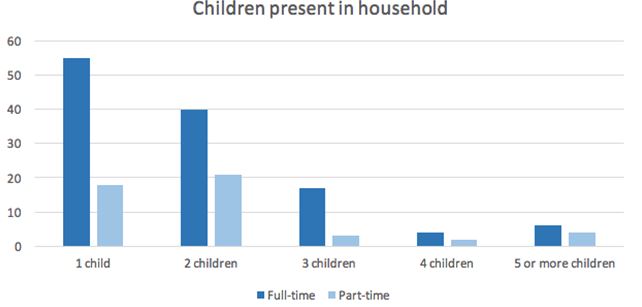

Almost one-quarter of the survey respondents (23.2%) said that at least one child under the age of 19 lives full-time in their household under the care of at least one parent or guardian, and 8.7% said that at least one child lives part-time in their household under the care of at least one parent or guardian.

To summarize, the respondents to our survey tended to be younger, with higher levels of education and higher employment rates than the general Canadian population. Twice as many respondents identified as female than male, and roughly equal numbers of respondents described themselves as heterosexual and bisexual. Most respondents involved in polyamorous relationships at the time of the survey were involved in a relationship with two other people. However, a significant number of respondents were involved in relationships with more than three other people and the members of most respondents’ relationships live in two or more households.

Surveyed polyamorists highly value equality in relationships and family decision-making

The survey also explored attitudes toward polyamorous relationships and the people involved in them, and about their perceptions of the attitude of the general public toward polyamory.

On the whole, respondents strongly endorsed the equality of members of their relationships, regardless of gender and parental status. More than eight in 10 respondents (82.1%) strongly agreed and 12.5% agreed with the statement that everyone in a polyamorous relationship should be treated equally regardless of gender or gender identity. More than half (52.9%) strongly agreed and 21.5% agreed with the statement that everyone in a polyamorous relationship should be treated equally regardless of parental or guardianship status.

Likewise, a large majority of respondents agreed that all members of their relationships should have a say about changes in those relationships. About eight in 10 (80.5%) strongly agreed or agreed that everyone in a polyamorous relationship should have an equal say about changes in the nature of the relationship, and 70.3% strongly agreed or agreed that everyone in a polyamorous relationship should have an equal say about introducing new people into the relationship. More than nine in 10 respondents (92.9%) strongly agreed and 6.3% agreed with the statement that each person in a polyamorous relationship should have the right to leave the relationship if and when they choose.

Respondents’ conviction in the equality, autonomy and participation of the members of their relationships likely explains another important finding from our research: 89.2% of respondents strongly agreed and 9.2% agreed with the statement that everyone in a polyamorous relationship should have the responsibility to be honest and forthright with each other.

The views of the general public toward polyamory have doubtless been complicated by the popularity of television shows dealing with polygamy, such as Sister Wives, My Five Wives, another TLC offering, and Big Love, from HBO, and by the publicity attracted by the recent criminal prosecution of a number of community leaders from Bountiful under s. 293 of the Criminal Code. The views of respondents themselves have also been influenced by the Criminal Code, sections 291 and 293 of which respectively prohibit bigamy and polygamy.

Although most respondents said that public tolerance of polyamory is growing (72.6%), more than eight in 10 (80.6%) agreed that people see polyamorous relationships as a kind of kink or fetish. Furthermore, only 16.7% of respondents agreed that people see polyamorous relationships as a legitimate form of family.

Polyamorous families have a unique and complex relationship with the law

The responsibilities of people involved in long-term, committed polyamorous families tend to be complicated, especially when those responsibilities must intersect with people outside the family, government services and the law. The difficulties faced by polyamorous families, especially those with children, cover every aspect of life in Canada:

- Who will schools recognize as parents and guardians, entitled to pick children up from school, give permission for outings or talk to teachers about academic performance?

- Who can get information from and give instruction to doctors, dentists, counsellors and other health care providers?

- Who can receive benefits from an employee’s health insurance? Who is entitled to coverage under provincial health care plans (e.g., OHIP in Ontario or MSP in British Columbia)?

- Who is entitled to claim public benefits such as the Old Age Security spousal allowance or Canada Pension Plan survivor’s benefits?

- What are the rights and entitlements of multiple adults under the provincial legislation on wills and estates, or the federal legislation on immigration?

- How many adults may participate in the legal parentage of a child under the legislation on adoption and assisted reproduction?

- What are the rights and entitlements of individuals leaving polyamorous families under the provincial legislation on domestic relations?

Many of the answers to these questions come down to how the applicable laws, policies and rules define terms such as parent, spouse and guardian, adult interdependent partner in Alberta, or common-law partner under most federal statutes.

The responsibilities of people involved in long-term, committed polyamorous families tend to be complicated, especially when those responsibilities must intersect with people outside the family, government services and the law.

Although schools and hospitals tend to look at the nature of the relationship between the individuals in question rather than a textbook definition of “parent,” agencies providing benefits tend to cleave more rigidly to narrowly defined terms. Some polyamorous families, for example, have been required to decide which of the adults in their family will be deemed to be an employee’s “spouse” for the purposes of health care and prescription coverage, resulting in the coverage of the employee and the family member selected as his or her spouse, but the denial of benefits to others.

The most urgent of these questions, however, likely relate to individuals’ entitlements and obligations under the provincial legislation on domestic relations. When committed polyamorous relationships come to an end, the same range of problems tend to arise as those faced by people ending monogamous relationships. Depending on the circumstances, the departure of one or more members of a polyamorous family may result in disagreements about: where children will live, how parenting decisions will be made and how much time the children will have with whom; whether child support must be paid, and if so who must pay it; whether a person is entitled to spousal support, and if so who is responsible for paying it; and how property and debt will be distributed, and whether an individual is entitled to an interest in property owned only by other family members.

When committed polyamorous relationships come to an end, the same range of problems tend to arise as those faced by people ending monogamous relationships.

On the whole, the legislation of the common law provinces tends toward the generous extension of rights and duties relating to children but takes a more parsimonious approach to spousal support and the division of property.

In keeping with the child-first approach of the Child Support Guidelines, the statutes of Canada’s common law provinces all impose a liability for child support on persons who are step-parents or stand in the place of a parent to a child, whether anyone else is subject to a pre-existing child support liability or not. As a result, all members of a polyamorous family are potentially liable to pay support for a member’s child, particularly where the child’s primary residence was the polyamorous household.

A dependent adult family member may be entitled to spousal support from another member of a polyamorous family if:

a) the person is a married spouse of the other member; or,

b) the person qualifies as an adult interdependent partner (Alberta), an unmarried spouse (British Columbia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan), a partner (Newfoundland and Labrador) or a common-law partner (Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia) of another member.2

A dependent adult family member may be entitled to spousal support from more than one family member where the legislation is not written so as to preclude the possibility of concurrent spousal relationships, as it is in Alberta, or the person qualifies as an unmarried spouse or partner of those members, as may be the case for families living in British Columbia.

In all of the common law provinces but Alberta and Manitoba, a child’s parents may share custody of the child, as well as the associated rights to receive information about the child and make decisions concerning the child, with:

a) other family members who fall within the statutory definition of guardian (British Columbia, Nova Scotia) or parent (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario, Prince Edward Island); and,

b) any other family members where the legislation does not require a biological relationship to apply for custody (British Columbia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan).

The legislation of British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador additionally allow more people than the biological parents of a child to have standing as the legal parents of that child when the child is conceived through assisted reproduction.

In all of the common law provinces except Manitoba, a child’s parents may share guardianship of the child, and the associated obligations as trustees of the child’s property, with one or more other family members.

With the exception of British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, statutory rights to the possession and ownership of property are restricted to married spouses in the common law provinces, limiting the relief available to the unmarried members of a polyamorous family to:

a) the legislation generally applicable to co-owned real and personal property; and,

b) whichever principles of equity and the common law might apply in the circumstances of the relationship.

The statutory property rights available to the members of polyamorous families in British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan arise from the application of the legislation to unmarried spouses (British Columbia, Saskatchewan) and common-law partners (Manitoba), and the failure of the legislation to preclude the possibility of concurrent spousal relationships.

A look down the road

The traditional model of the Western nuclear family, consisting of married heterosexual parents and their legitimate offspring, which prevailed almost unaltered for more than 1,000 years, has been evolving at an ever-increasing pace since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, along with the legal concepts and structures that support it. The legal disabilities of married women, such as their inability to own property or conduct business in their own names, were the first to go, followed by the disabilities associated with bastardy, such as the inability to inherit or assume their father’s title.

The federal Divorce Act first allowed Canadians to end their marriages other than by dying in 1968, and the baby boomers, the oldest of whom turned 65 in 2011, are the first generation to have lived almost the whole of their adult lives under federal divorce legislation. Not only has the stigma associated with divorce largely evaporated, but the rate of remarriage and repartnering has continued to rise over the last two decades, as has the number of blended families, which seem to now be as commonplace as unblended families.

Sexual orientation became a prohibited ground of discrimination in the mid-1990s, following which same-sex marriage became legal in Ontario in 2002, and in eight other provinces and territories in rapid succession thereafter, until the introduction of the federal Civil Marriage Act in 2005 legalized same-sex marriage throughout the country. Legislation giving unmarried cohabiting couples property rights identical to those of married spouses became law in Saskatchewan in 2001, in Manitoba in 2004 and in British Columbia in 2011.

In Canada, family is now thoroughly unmoored from marriage, gender, sexual orientation, reproduction and childrearing; the presumption that romantic relationships, whether casual, cohabiting or conjugal, are limited to two persons at one time is likely to be the next focal point of change.

The scant data currently available on polyamorous relationships suggest that the number of people involved in such families is not insignificant and may be increasing: according to a 2009 article in Newsweek, Loving More, a magazine aimed at polyamorous individuals, has “15,000 regular readers,” and more than 500,000 Americans live in openly polyamorous relationships; in Polyamory in the Twenty-First Century, author Deborah Anapol estimates that one in 500 Americans are polyamorous; and the website of the Canadian Polyamory Advocacy Association, polyadvocacy.ca, identifies two other national organizations supporting or connecting people involved in polyamorous relationships and eight similar regional organizations based in the Maritimes, 36 in Quebec and Ontario, 23 in the prairie provinces and 22 in British Columbia.

We have successfully accommodated significant, transformational change to how we think of family in the past, and we will do so again.

If the prevalence of polyamory is indeed increasing, a significant number of our most important social customs and institutions will need to evolve. This will require a reconsideration of how we think of parenthood and how we distribute the liabilities parenthood entails. It will also have an impact on how we demarcate those committed adult relationships that attract legal entitlements and obligations and those that do not, as well as how these entitlements and obligations are distributed among more than two people.

Although the magnitude of potential change is significant, it is not pressingly imminent; we have time to acclimate and adapt to the rising number of polyamorous individuals and families. We have successfully accommodated significant, transformational change to how we think of family in the past, and we will do so again.

Notes

- Survey data have not been weighted.

- Note that the legal situation in Quebec is different than in the rest of the rest of Canada’s provinces since it is governed by civil law rather than the common law system used in the other provinces. As such, it is beyond the scope of this article.

John-Paul Boyd, M.A., LL.B., is the Executive Director of the Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family, a multidisciplinary non-profit organization affiliated with the University of Calgary.

To learn more about John-Paul Boyd’s research into polyamorous relationships and family law, see “Polyamorous Families in Canada: Early Results of New Research from CRILF” from the Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family.

Download this article in PDF format.

Published on April 11, 2017