May 22, 2025

“Who Is Family and Why Should We Care?”: A Conversation About Family Diversity and Wellbeing

As part of our 60th anniversary, the Vanier Institute of the Family recently partnered with the Department of Human Ecology at the University of Alberta to host the panel discussion “Who Is Family and Why Should We Care?”

Three panellists from diverse personal and professional backgrounds came together to discuss how “family” is understood and defined, by family members themselves and the policies that affect them. Norah Keating, a global family scholar, social gerontologist, and former Board Chair at the Vanier Institute, moderated the discussion to cover different perspectives brought by each member of the expert panel:

- Yue Qian, Associate Professor of Sociology at University of British Columbia, whose research focuses on family, gender, and inequality

- Sue Languedoc, recently retired Executive Director of Aboriginal Counselling Services Association of Alberta

- Doug Stollery, lawyer, member of the Order of Canada, and co-counsel in Vriend v Alberta, the first successful case in support of 2SLGBTQ+ rights before the Supreme Court of Canada

The panellists share their unique perspectives on family, which have been edited for length and clarity in the following summary.

Sue Languedoc: I was executive director and co-founder of Aboriginal Counseling Services, which was founded back in 1992—I retired seven months ago. I’m here to bring the voice of the ladies, men, kids, and all the people that I’ve worked with throughout my career.

That word “family” is a loaded word in the work that I’ve been doing, because I work with family violence. I work with child abuse, spousal abuse, and dating violence. What the people I work with have taught me is that, particularly in the context of the intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous communities, people who come to us are already dragging a suitcase full of trauma with them, a lot of which has come from the hands of people who say they are “family.” In my career, the challenging part was trying to help people understand that sometimes family isn’t the typical warm, fuzzy ideal. Sometimes, family can be a threat. Sometimes, family is not a source of support because the people in their family didn’t learn those skills or have those tools either.

When we talk about intergenerational trauma and abuse, we see that generations of families are trying to move forward, a little bit better than maybe their relatives did. They’re trying to find a way. Because of the history of what’s happened to the Indigenous community, a lot of those ties were severed, deliberately, so that people didn’t know their families. As a social worker, when we start working with people, we ask them to tell us about their family. This is a difficult, traumatic thing for some people to do, and it’s important to be mindful of that.

Last year, we had some surplus money from the United Way, and I decided that I wanted to use it to do something for the clients that were coming to our agency. Some had experienced family violence, some were in therapy, some were there because they had anger issues and were mandated to attend. I thought, what if we brought in a professional photographer to take some family photos with the clients together, who could bring their families in. But then we stopped and went, “Oh… that word… family portrait?” We knew it can be a loaded word. So, we changed it, and instead asked, “Who do you have in your circle of support?” We took these beautiful professional photographs of clients who wanted to participate, and they brought in whoever was in their circle of support. It didn’t even have to be a person—it could be a dog or a stuffed animal.

I don’t really think any of us have the right to define who someone else’s family is, but I do think we have the right to ask who supports you. The people that I’ve worked with over the years found a circle of support that brought them comfort, and the people in their circles often weren’t from their biological families. And when I think of that word family, that’s what I’d like it to mean: comfort and safety.

Yue Qian: I have a couple of stories to share that highlight the mismatch between what people think of family and what laws and public policy say about it. In the first, people don’t consider themselves to be family, but policy says that they are. The second story is about people who do consider themselves family but policy disagrees.

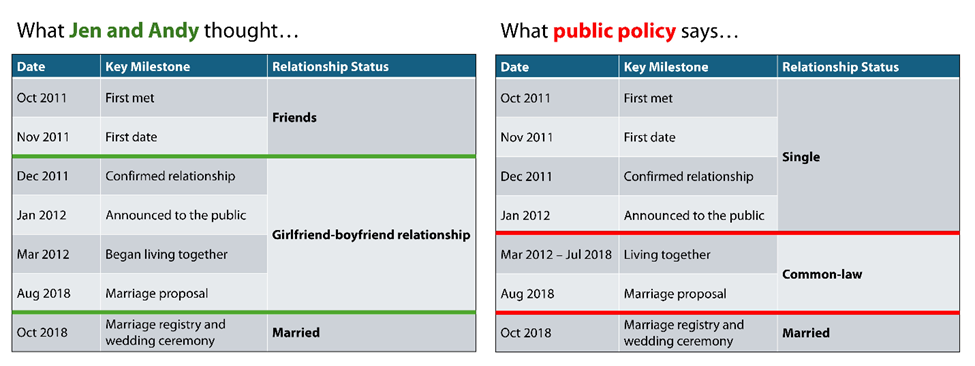

The first story is about Jen and Andy, an Asian immigrant couple living in British Columbia (names have been changed to maintain confidentiality). This table I’ve prepared [see below] shows some of the key milestones in the development of their relationship. Over a seven-year period, they met, dated, moved in together, and then got married.

How did they think about their relationship? The way they see it, they were friends at first, and then they were girlfriend and boyfriend, and then they eventually got married. But the law sees it differently. According to the BC Family Law Act, the date that their common-law relationship is deemed to have begun is the date on which the partners began to live together in a “marriage-like relationship.” The law sees them as having been in this kind of relationship for six years before they were legally married.

In many cultures, the concept of a common-law relationship doesn’t exist. Even in Canada, many people are not aware of the legal implications of being in a common-law relationship, which in many cases (although not all) are treated like marriage, regardless of what the couples intended.

In Jen and Andy’s case, after they married, Andy applied to sponsor Jen’s immigration to Canada. However, immigration officers found that Andy had marked himself as “never married” on his permanent residency application, even though according to the BC Family Law Act, he was in a common-law relationship at the time. As a result, his sponsorship was denied, and his own permanent residency was at risk of being revoked. As you can imagine, this young couple was under immense stress.

I want to use this case to highlight a broader issue: although Canadian law aims to recognize diverse family forms, in practice, it forces couples into a marriage-like legal status. While marriage requires an active decision, common-law status is automatic after one, two, or three years of cohabitation, depending on the province. This means that many couples don’t choose to be legally bound, it’s decided for them by the state. Ultimately, the law offers only one option for cohabiting couples—marriage, or something that that is legally almost identical.

That was a story of a couple who didn’t think they were family but policy decided otherwise. The opposite happens as well. Many of you have heard that the Government of Canada recently announced that it is indefinitely pausing new permanent residency sponsorship applications for parents and grandparents. How immigration policies see parents and grandparents contrasts sharply with how it views children. Young children are considered dependants of principal immigrant applicants, and are therefore admitted as accompanying immediate family.

The current definition of “dependants” in Canadian immigration law is rooted in what sociologists have called the “Standard North American Family,” which emphasizes parents and young children living in the same household as a family. In many other cultures, though, parents and grandparents are considered integral parts of the family household—something our current public policy has yet to sufficiently recognize.

These two stories help to highlight that the question of “who is family” is often answered differently by people and by public policy, and this mismatch has implications for family wellbeing that need to be addressed.

Doug Stollery: Let me start by saying that I lack the academic expertise of the other members of our panel, and perhaps many members of the audience. I would like to speak about this theme from perspectives from which I do have some experience, first as a lawyer and second as a gay man.

As a lawyer, I would offer these observations. One of the lenses of the Family Diversities and Wellbeing Framework looks at family structure. In the English language, many words have multiple meanings, which depend on the context in which they’re used. Think, for example, of the word “pool”: it might be somewhere where you swim or a game that you play with cues and balls, or it could refer to joining things together, as in pooling resources. I think that having more than one definition for the word “family” is consistent with the way in which we use our language.

To me, context is key. In the context of family medical history, such as the genetic disposition to certain medical conditions, we focus on biological parents and grandparents, perhaps aunts and uncles and cousins, regardless of the relationship we may have with them, and regardless of whether we even know them. So, in this particular context, we’re not looking at adopted parents or children. We’re also not looking at spouses or a person’s community of support.

In some contexts, relationships of support are critical, and I expect we will talk about that more this afternoon. That might be contrasted with the context of family violence, where we’re looking at intimate relationships or blood relationships that are relationships of abuse, not relationships of support.

Looking at the law, different definitions of family may apply for different benefits and responsibilities. In some cases, family is defined without any requirement of a relationship of support. One example of this is intestate succession, which deals with who in a family receives inheritance if there is no will. In Alberta, beneficiaries under intestate succession include spouses or partners, lineal descendants, and parents—in that order. In this context, family is defined by marriage and bloodlines, regardless of any relationship of support. In other cases, a relationship of support is the defining factor. For example, eligibility criteria for the Canada Child Benefit look at the relationship between a child and a person (or persons) primarily responsible for that child. This could be a biological parent, adoptive parent, or any person standing in loco parentis (which means “in the place of a parent,” someone who effectively acts as a parent, taking on certain responsibilities typically held by a parent).

Sometimes, law creates a duty of support. For example, in Canada’s Criminal Code, Section 215 imposes a legal duty of support on a parent, foster parent, guardian, or “head of the family” to their children under the age of 16, and in some cases to their spouse or partner. Another example is the Alberta Wills and Succession Act, which imposes a legal duty to provide adequate support to family members in your will. Here, a family member is defined as a spouse or partner, a child under 18, a child between the ages of 18 and 22 if they are in full-time studies, a grandchild, or great-grandchild.

These are just provided as examples, and I’m not intending to discuss whether any of these definitions are appropriate. The point I’m trying to make is that the way in which we define family may depend on the context in which we use the term and the purpose we’re trying to achieve. If I can throw out a suggestion, I think that we should start by determining what it is that we’re trying to achieve with it. We should then determine what definition of family or what set of relationships best achieves that goal. At both of these steps, it is critical that we consider the issue of inclusivity. Is the definition limited by stereotypes? Is the goal that we’ve set limited by stereotypes? Are we leaving anyone out who should be included? For legal purposes, a “one-size-fits-all” definition may not work, because it is likely to be over-inclusive in some cases and under-inclusive in others.

In addition to the legal consequences associated with the definition of family, there are also important social consequences. Being a member of a family establishes a certain status in society, and in that context, I think the relationships of support are particularly important. Identifying a “relationship of support” is very much an individual determination. In this context, I suggest that each person should have the right to define their own family. That might be persons with whom you are linked biologically. It might be your spouse and children, or it might be a close circle of friends or the community with which you associate.

Moving on to my perspective as a gay man, I’d like to offer some more personal observations related to both the family structure and the family identity lens. Many of my experiences will likely also be true to some degree of members of the lesbian and bisexual communities. As a cisgender man, I can’t and don’t speak for members of the transgender community, but I expect that some of the same experiences are likely true, although probably to a greater degree, particularly in the current political landscape.

My first observation is that throughout history, gays and lesbians have often been excluded from the definition of family. Think, for example, of the term “family values,” particularly as espoused by the late Anita Bryant. Her argument was that even the recognition of even basic human rights for gays and lesbians would undermine the family, and thereby all of society. For her, just being gay was antithetical to the family. This argument held significant political sway at the time and continues to hold force in some quarters today. To me, it’s truly unfortunate that a term like “family values”—which properly used, should have positive connotations—has come to be used in some circles as a term of discrimination.

As another example, think of the prohibition against same-sex marriage and same-sex adoption that existed in Canada until about 20 years ago. Until then, the law was structured to prevent gays and lesbians from establishing their own families. A good example of this is Ralph Klein’s amendments in the year 2000 to the Alberta Marriage Act. For context, I was counsel in the case of Vriend v Alberta, which was the first successful gay rights case before the Supreme Court of Canada. That decision established that it was unconstitutional for Alberta to refuse to provide protections in its human rights legislation against sexual orientation discrimination.

Once the Vriend decision came out in 1998, there was very strong pressure on the Klein government to invoke the notwithstanding clause and override the decision of the Supreme Court. He ultimately decided not to invoke the notwithstanding clause, but as a compromise to elements in his party, he said that he would “draw a fence around marriage” in other legislation. He amended the Marriage Act to state that the prohibition of same-sex marriage was necessary to preserve the “purity” of marriage. In other words, allowing same-sex marriage would make the institution of marriage “impure” in some way, and because marriage is often regarded as a central pillar of the family, it would therefore somehow stain the institution of the family.

This time he did invoke the notwithstanding clause, to prevent Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms scrutiny of these amendments to the Marriage Act. The legislation was unconstitutional in any event, because this is the purview of the federal government and not the province, but it sent a “strong and sinister message” that same-sex couples were a threat to marriage and to the family. The phrase “strong and sinister message,” by the way, comes from the Supreme Court’s Vriend decision.

My second observation is that the traditional family, which ideally should be an institution of support, has sometimes been one of the greatest risks for gays and lesbians. One of the factors about being gay or lesbian is that you can often conceal that fact to avoid discrimination by remaining in the closet. In many families, children are assumed by their family members to be straight until they come out. For many, one of the greatest risks of coming out is the family’s reaction. The family may either be a critical source of support, or a source of abuse. It’s not always easy to tell what their reaction will be unless and until you take the chance of coming out.

To be clear, things have improved enormously over the course of my life. As I was growing up, gays and lesbians were criminals because of who they were. Engaging in same-sex relationships was a criminal offense until 1969. When I was in university shortly after decriminalization in the early 1970s, discrimination remained rampant. To be openly gay was to be unemployable. Over the course of my five years at this university, I did not meet one openly gay person.

Today, same-sex relationships are no longer criminal. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is prohibited, in particular in this province because of the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada on the Vriend case. Same-sex marriage is recognized in law. Same-sex adoptions and surrogacy are permitted. We have, I hope, moved as a society from the belief that gays and lesbians are a threat to the family to the recognition that gays and lesbians may form their own family units.

But as we gather here today, some of this progress may be at risk. In the United States, the federal government is acting to prohibit steps to support the values of diversity, equity, and inclusion. We are seeing signs of this spilling over from government to the corporate sphere. Donald Trump has signed an executive order effectively declaring that transgender persons do not exist, ironically, while signing another executive order prohibiting these “non-existent” transgender persons from serving in the military. There is some risk that the US Supreme Court may, at some point, overturn its own ruling recognizing the Constitutional status of same-sex marriage.

In Alberta, legislation has just been passed to prohibit parents from making critical decisions about the health care of their transgender children, again, ironically, while touting the fundamental importance of “parental rights.” In another piece of legislation, Alberta has prohibited teaching in schools about sexual orientation or gender identity, unless parents opt in to allow that education to be provided. The exclusion of certain students from these discussions sends another “strong and sinister message” to straight, gay, transgender, and cisgender students. These are all risks to the progress that we have made in the recognition of the fundamental dignity of members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community within our society and in our understanding of what constitutes a family.

This highlights the importance of discussions like this to understand the meaning of family and to support the inclusion of everyone within that meaning.

To summarize, looking through the Family Structure lens, I suggest that how we define a family needs to be both inclusive and flexible. It needs to reflect the context in which that term is used. From the Family Identity lens, we’ve made great strides in the inclusion of the 2SLGBTQ+ community within the societal understanding of what is a family, but we need to be vigilant in protecting this progress and in continuing to work to break down barriers.

Stay in the know

InfoVanier

A monthly newsletter of research, resources, and events

Linktree

Get alerts on new Vanier Institute publications, events, and announcements