January 18, 2021

Research Recap: Divorced and Unpartnered: New Insights on a Growing Population in Canada

Research recap by Rachel Margolis, PhD, and Youjin Choi, PhD

January 19, 2021

Originally published on March 30, 2020

STUDY: Rachel Margolis, PhD, and Youjin Choi, PhD, “The Growing and Shifting Divorced Population in Canada,” Canadian Studies in Population 47(1–2) (February 17, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/39u1uv3.

Throughout much of the 20th century in Canada, divorce was a relatively uncommon family experience, due primarily to conservative social norms and a legal framework based on restrictive grounds for ending a marriage.1 This changed in the1970s, as a variety of intersecting social, cultural and legal factors contributed to an increase in divorce rates, not only in Canada but also in the United States and many European countries.

Past research on divorce in Canada has focused on lone-parent households2, 3 or the correlates and consequences of divorce.4, 5 We conducted a study, “The Growing and Shifting Divorced Population in Canada,”6 published in Canadian Studies in Population, that addresses key knowledge gaps on the divorced population in Canada and how it’s evolving, with a focus on divorced adults who were currently unpartnered (not remarried or not living with a new partner). People in this segment of population experience the financial situation of not having another adult with whom to share household costs. Census and population estimate data were used to explore how the population of divorced and unpartnered adults has grown over the past three decades, to measure levels of economic well-being for these men and women, and to assess how the divorced population is faring economically relative to their married/partnered counterparts.

Social and legal trends have shaped divorce in Canada

Evolving social and legal contexts in Canada had a significant impact on divorce trends across generations. While intersecting factors (such as the women’s rights movement, the declining influence of religious sanctions against divorce and the increased financial independence of women resulting from their growing involvement in the workforce) reduced some of the stigma of divorce and economic dependence on marriage, changes in family law eliminated some of the barriers faced by women who wanted to divorce.

The 1968 Divorce Act made it easier to obtain a divorce by establishing no-fault divorce after a three-year separation, and this act was amended in 1986, when the mandatory separation period was reduced to one year. These complex and interrelated developments had an impact on divorce rates and the number of divorces, which both increased from the 1970s to the 1990s and then stabilized in the following decades.7

These changes led to unique generational experiences with divorce. Baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1965) were the first cohort to experience large increases in marital dissolution in young adulthood, high rates of cohabitation and non-marital childbearing, and this age group continues to have relatively high rates of marital dissolution at older ages. This group is the most likely to have ever experienced divorce and is also most likely to be currently divorced. More recent birth cohorts saw the growing prevalence of non-marital cohabitation (i.e. living common-law) as a family structure and living arrangement, as well as lower marriage rates and an increasing average age of first marriages.

KEY FINDING 1: Canada’s divorced population is growing rapidly

Our research shows that it is becoming more common for adults in midlife (ages 50–59) to be currently divorced and unpartnered. For example, for adults who were born between 1921 and 1930, 4% were divorced and unpartnered in their 50s. For the next cohort born in the 1930s, 7.2% were divorced and unpartnered in their 50s. Among those born in the 1940s and 1950s, this number reached 11%.

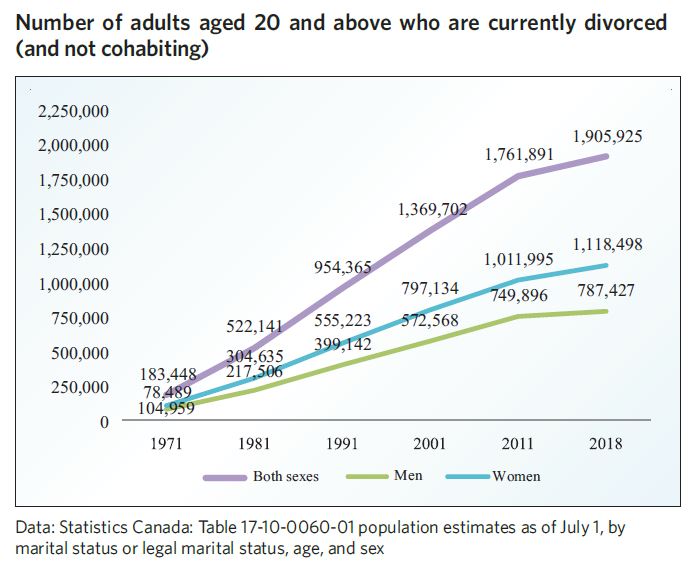

The fact that being divorced and currently unpartnered is becoming more common across generations, combined with population growth and population aging, means that the divorced population is growing rapidly. The figure below shows the number of adults aged 20 and above who are currently divorced and unpartnered (and not cohabitating) in Canada. Data showed that the number of currently divorced adults increased more than tenfold between 1971 and 2018 – from approximately 183,000 to 1.9 million.

KEY FINDING 2: Canada’s divorced population is becoming “greyer”

As a group, divorced Canadians are getting older, reflecting the more general trend of population aging in Canada. Three in 10 were aged 20 to 39 years in 1991, but this fell to 7% by 2016. Over the same period, the proportion of divorced adults8 who were aged 60 or older more than doubled from 16% to 44%.

The fact that many divorced and unpartnered adults are older adults means that many of them are not currently in the labour force. For example, just over half of these adults were employed and one quarter live with low income, either as individuals or in a low-income family. Moreover, more than half live alone, and fewer than 6 in 10 own their residence.

KEY FINDING 3: Divorced women are better off than in the past; not so for men

This study also examined the economic well-being of the divorced population and whether the economic disadvantage of divorced women relative to men has decreased over time. In analyzing how the gender gap in economic well-being has changed from 1991 to 2016, evidence suggests that there was a large degree of gender inequality among the divorced population in 1991, which has gradually decreased.

For example, all else being equal, in 1991, divorced and unpartnered women earned approximately 19% less than their male counterparts.9 This gender gap in earnings decreased overtime, falling to 5% in 2016. Divorced men still earn more than divorced women, but the gap has narrowed. Similarly, in 1991, divorced women were 8 percentage points more likely to live in a low-income family than men. This gap gradually narrowed to just 2 percentage points in 2016. The narrowing gap for these measures of economic well-being represents circumstances that improved for divorced women but stagnated for divorced men.

Overall, a gendered analysis of trends in economic well-being among divorced and unpartnered Canadians since 1991 shows that there has been significant progress for divorced women – particularly with regard to employment status and likelihood of living in a low-income family – but that their economic well-being is still far below that of married women. Divorced and unpartnered men, on the other hand, have experienced little to no progress, experiencing economic stagnation and economic disadvantage, and are even more disadvantaged when compared with married men.

Unpartnered divorced adults are an economically vulnerable group, as they have experienced the economic shock of divorce, may have to pay (or may not receive) child and/or spousal support payments, and do not have a live-in partner on which to rely for social or economic support.

Conclusion

This study made significant contributions to our understanding of the divorced population in Canada, revealing a growing and aging population with some key economic vulnerabilities. Data showed that divorced women are much less economically disadvantaged than in the past. However, divorced and unpartnered men have not seen the same kinds of economic improvement as women. Our findings highlight the increasing economic vulnerability of divorced adults in Canada, especially relative to the married population, and point out how divorced adults may have risk profiles that deserve more attention.

As the divorced population in Canada continues to grow, measuring and understanding well-being among this group will likely become a growing focus for decision-makers and policy-makers across the country.

Rachel Margolis, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Western Ontario and a previous Vanier Institute of the Family contributor.

Youjin Choi, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Western Ontario.

This research recap was reviewed by Rachel Margolis, PhD.

- Anne Milan, “Marital Status: Overview, 2011,” Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 91-209-X (July 2013). Link: https://bit.ly/38AGPVg.

- Don Kerr and Roderic Beaujot, “Family Relations, Low Income, and Child Outcomes: A Comparison of Canadian Children in Intact-, Step-, and Lone-Parent Families,” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 43(2) (2002). Link: https://bit.ly/2udaxkx.

- Enza Gucciardi, Nalan Celasun and Donna E. Stewart, “Single-Mother Families in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 95(1). Link: https://bit.ly/39KuZIL.

- Margaret J. Penning and Zheng Wu, “Caregiving and Union Instability in Middle and Later Life,” Journal of Marriage and Family 81(1) (October 4, 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/2wvZC6p.

- Zheng Wu and Margaret J. Penning, “Marital and Cohabiting Union Dissolution in Middle and Later Life,” Research on Aging 40(4) (April 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/2SFdTX4.

- Rachel Margolis and Youjin Choi, “The Growing and Shifting Divorced Population in Canada,” Canadian Studies in Population 47(1-2) (February 17, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/39u1uv3.

- See Anne Milan, “Families and Living Arrangements,” Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 89-503-X (November 10, 2015). Link: https://bit.ly/2V45NsD.

- Aged 20 and older.

- As with percentages, all dollar amounts in this article have been rounded to the nearest hundred. Precise figures can be found in the original study.

Stay in the know

InfoVanier

A monthly newsletter of research, resources, and events

Linktree

Get alerts on new Vanier Institute publications, events, and announcements