Nicole Denier is a sociologist with expertise in work, labour markets, and inequality. She has led award-winning work on the intersection of family diversity and economic inequality, including research on the economic wellbeing of 2SLGBTQI+ people in Canada and immigrants in North America. Nicole is currently an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Alberta. She serves as Co-Director of the Work and Family Researchers Network Early Career Fellows program, as well as on the editorial boards of Canadian Studies in Population and the Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie.

Topic: Technology

Yue Qian

Yue Qian (pronounced Yew-ay Chian) is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. She received her PhD in Sociology from Ohio State University. Her research examines gender, family and work, and inequality in global contexts, with a particular focus on North America and East Asia.

Issue Brief: Considering Families in Canada’s Digital Transformation

An overview of how technological change relates to inequalities within and between families

Research Snapshot: The Relationship Between Fathers’ Social Media Use and Their Food Parenting Practices

Highlights of a study of how parents use social media and how it relates to their parenting practices around food

Caregiving During COVID: What Have We Learned? (Video)

Alex Foster-Petrocco shares takeaways and highlights from a recent webinar on caregiving and technology during COVID-19.

Diblings Asking “Who Am I?” – Searching for Answers, Finding More Questions

Sara MacNaull and Nora Spinks

August 13, 2020

“Who am I?” is an age-old question. A growing number of people around the world who are looking at this question, through a family lens, are discovering that they are part of a unique, emerging family relationship, as a “dibling.” The term dibling, which stems from “donor sibling” or “DNA sibling,” is someone with whom you share genetic material – from at least one or both parents – resulting from reproductive technologies or fertility treatments.

People’s curiosity about their origins has been ignited thanks to the mass digitization of historical documents and increased access to records, including birth records, immigration papers and marriage certificates. The growing availability and affordability of DNA testing has meant more people are spitting into a tube or swabbing a cheek and sending off their genetic material for analysis. Pop culture has provided a mirror of this trend in society through television shows such as Who Do You Think You Are?, Long Lost Family, Genealogy Roadshow, Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Ancestors in the Attic. Fictitious TV dramas profiling diblings – such as Sisters in Australia or its American remake, Almost Family – are also generating popular interest in the dibling phenomenon.

According to estimates published in MIT Technology Review1 in 2019, more than 26 million people have submitted their DNA to the four leading commercial ancestry and health databases (e.g. AncestryDNA and 23andMe). As a result, family lore is being rewritten, family mythology is being debunked, decade- or century-old questions are being answered, subsequent questions are being asked, and some previously unknown facts are being revealed. Truth is coming to light about ancestors who had once been hailed as heroes, only for DNA or genealogy to reveal that there was more to the story than what had been passed down from one generation to the next, such as a sister who’s actually a mother or a father who’s not a blood relative.

Debunking family lore

Family lore often glamourizes, exaggerates, or even covers up the truth – including socially unacceptable behaviour, crimes, or dishonour brought upon the family. Family lore reduces stigma, helps foster public acceptance or changes family members’ perceptions of a person or event. Consider the story shared at a recent Listening Tour event hosted by the Vanier Institute about a revered late uncle:

“The participant’s great-grandmother’s brother – a fearless countryman, who was well-respected – was a hard-working farmer and fiercely protective of his family. Family lore claims he was thrown from his horse on his way to help a neighbour during a terrible storm and died tragically on the side of the road, not to be found for days. Since his death he has been hailed as a hero, though now-accessible records reveal that your uncle was an alcoholic and had had several run-ins with the law. His death – though still tragic – was, in fact, the result of a late night at the local watering hole.”

And, just like that, the truth is revealed, family stories and identities altered, and the perceptions of others changed, all as a result of access to DNA testing and to public and genealogical records. Our ancestors could never have imagined what would exist one day – for all to see.

A new type of “family”

For M. (name withheld to protect privacy), submitting her DNA for testing was just for fun. Though she had recently learned, in her 30s, that the dad she had always known was not her biological father, she had no desire to find the latter. However, like many others, she took the test, shipped it off and waited. When the results arrived, there were no real surprises. Her ancestors came from the countries she expected and easily explained certain physical characteristics. However, within hours, she started receiving notifications that revealed “close DNA matches” from around the world. Within days, the number kept increasing, eventually exceeding 30 – that is, 30 biological half-siblings, previously unknown to her, now confirmed through DNA testing.

“It was quite overwhelming, to be honest,” M. stated in a recent interview with the Vanier Institute of the Family. “I never imagined I’d find anyone who was related to me, except for perhaps a distant cousin. I had no reason to think I had multiple diblings.”

M.’s family story may seem unique, yet she is not alone in her experience or discovery. Many others are finding new or lost relatives, sometimes asking their parents or extended family awkward questions, and considering tough decisions about whether to foster new relationships with their diblings.

Delaying motherhood in Canada

Families in Canada, like elsewhere, are diverse, complex and ever evolving. Families are formed through various means, such as birth, adoption, coupling, uncoupling or by choice. In Canada, the fertility rate, or average number of children per woman, has been steadily decreasing since 2009, reaching a low point in 2018, at 1.5 children, compared with 3.94 in 1959).2, 3

Women across the country are increasingly waiting longer to have children. In fact, the fertility rates of women in their early 20s and late 30s flipped over the past 20 years. In 2018, the fertility rate in Canada for women aged 20 to 24 stood at 33.8 live births per 1,000 women, down from 58 per 1,000 in 2000, while the fertility rate in Canada for women aged 35 to 39 was 57.1 live births per 1,000 women, nearly double the rate in 2000 (34 per 1,000).4, 5 Given that many women are delaying having children – either by choice or circumstance – the mean age of mothers at time of delivery was nearly 31 years of age in 2018 (30.7 years), a trend that has been on the rise since the mid-1960s.6, 7

Motherhood and reproductive technology

The choice to delay motherhood for women may be the result of focusing first on post-secondary education and career development – continuing a long-term trend observed over the past several decades.8 Sometimes circumstance – not choice – is the driving factor, such as for those who have not met a partner with whom they want to have a child. As a result, some women are choosing to embark on the journey solo, with recent figures showing that the proportion of babies born to single (never married) women in 2014–2018 (the most recent years in which data is available) hovers around 30%.9, 10 This road to motherhood may include the use of reproductive technologies or adoption, either domestically or internationally (within countries and jurisdictions that allow women to adopt without a partner).

Among couples, reproductive technologies and adoption are becoming more common routes to parenthood – particularly among LGBTQ couples. Since the 1980s,11 the proportion of couples who experience infertility has doubled, now 16% (or roughly 1 in 6 couples). These couples may choose insemination or invitro fertilization with the use of a sperm donor or egg donor, or both, which come with their own DNA and physical traits. For adoptees or adults who do not have information or a relationship with one or both biological parents, DNA testing provides an opportunity to reveal ethnicity, cultural background and affiliations, country of origin and close or distant relatives. As M. stated:

“At first, I was reluctant to engage with any of these DNA matches. Part of me questioned the accuracy of the testing and I had so many more questions than when I started. I was confused as to how I was connected to these people. Within a few days of getting my results, I had to turn off the notifications on my phone. I just couldn’t keep up with all of them. This process led to even more soul-searching. I really had to think about and decide whether I was interested in getting to know these people, whether I was willing to put in the time, learn about them, share things about myself and my life, and genuinely foster relationships. Eventually, I went for it. I began replying to messages, receiving pictures and learning about how each one of my diblings came to be. Each story was so unique. All of a sudden, these 30+ strangers and I were trying to piece together a giant, global puzzle.”

Connecting with your diblings

For M., deciding to connect with her new family members included creating a list of pros and cons. The pros included the excitement of discovering the biological traits that stood out, whether others had the same interests or aptitudes as she did, and getting the chance to meet people from around the world – all of whom had the same starting point. The cons included managing her own expectations about what and how the relationships would develop (would they be forced or organic?), dealing with how her family would react to this discovery, and taking into account the feelings of the sibling she had grown up with. It also meant considering what all this meant for her biological father’s family, since, thanks to the DNA testing, it revealed that he had been married, and fathered and raised children in the area where she was currently living. She ultimately decided that the pros outweighed the cons, and within a few short months, an in-person meeting of some of the local diblings took place:

“The night before the gathering, I didn’t sleep a wink. I was so nervous about what I would learn and wondered whether I had made a mistake. And yet, upon arrival at the venue, I was struck by how familiar some of the other faces were, as if I had seen them before or met them before in a different context. I also couldn’t help but notice that some of us had some very similar features, more so than I had expected. Though the first few minutes felt a bit like speed dating or an awkward job interview, the conversation began to flow quite easily afterwards. Since then, we have met several times and are planning a diblings retreat where all of us come together from around the world.”

Though M.’s DNA discovery has a happy ending so far, others who have unlocked the DNA mystery door have dealt with unfortunate or difficult experiences. In a world where access, privacy, Big Data and DNA are colliding at a rapid pace, it is too soon to tell what the next few years will reveal about people’s personal histories and ancestry. All we can do is try to prepare ourselves for the unknown, the questions, the answers and the family stories, and whether we should decide to embark on the journey to discover “Who am I?”

Sara MacNaull is Program Director at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Nora Spinks is CEO of the Vanier Institute of the Family.

This article was originally published in Canadian Issues (Spring/Summer 2020), reprinted with permission from The Association for Canadian Studies. Link: https://bit.ly/2XWmWF9.

Notes

-

- Antonio Regalado, “More Than 26 Million People Have Taken an At-home Ancestry Test: The Genetic Genie Is Out of the Bottle. And It’s Not Going Back,” MIT Technology Review (February 11, 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/2DTARom.

- Claudine Provencher et al., “Fertility: Overview, 2012 to 2016,” Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 91-209-X (June 5, 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/3iAsJYY.

- Statistics Canada, Crude birth rate, age-specific fertility rates and total fertility rate (live births) (Table: 13-10-0418-01) (page last updated May 22, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/2XWsgbs.

- The Vanier Institute of the Family, “Mother’s Day 2019: New Moms Older, More Likely to Be Employed Than in the Past” (May 8, 2019).

- Statistics Canada, Crude birth rate, age-specific fertility rates and total fertility rate (live births).

- Statistics Canada, Mean age of mother at time of delivery (live births) (Table: 13-10-0417-01) (page last updated May 22, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/3alUWjb.

- Claudine Provencher et al., “Fertility: Overview, 2012 to 2016.”

- The Vanier Institute of the Family, “Mother’s Day 2019: New Moms Older, More Likely to Be Employed Than in the Past.”

- Statistics Canada, Live births, by marital status of mother (Table: 13-10-0419-01) (page last updated May 22, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/2E3Ztus.

- This figure may also include women who are living common-law and who are therefore partnered but not legally married.

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Fertility (page last updated May 28, 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/322khLB.

Published on August 13, 2020

Families in Canada Adapting: A Wedding at a Distance

While the COVID-19 pandemic has affected families across Canada and the social, economic, cultural and environmental contexts that impact their well-being, it hasn’t stopped family life by any means.

Whether it’s managing work–family responsibilities, connecting to celebrate milestones or providing support in difficult times, people are finding diverse and creative ways to keep doing what families do.

As families in Canada continue to manage these transitions, the Vanier Institute of the Family is gathering, compiling and sharing these “stories behind the statistics” to provide insights and into family strengths, resilience and diverse experiences across the country.

A Wedding at a Distance

Edward Ng, PhD

June 1, 2020

In early May, I had my first experience attending an online wedding. The event was planned long ago, well before the COVID‑19 pandemic had been declared. Once the restriction order was imposed in mid-March, the couple adjusted the wedding plan so that the event could be held online instead.

The ceremony, which was held in Montreal at the home of the bride, was ultimately broadcast through YouTube all over the world. Will this be the trend of the future? Before this, my only “virtual family gathering” was a funeral for my uncle who passed away a few years ago in Sydney, Australia.

The ceremony started at 10:30 a.m. on a Saturday morning (or wherever it happened to be for the online guests). After introductory music, the flower girl and the ring bearer made their entry into the broadcasting not by walking down the aisle in a church but rather their own corridor at home, throwing flowers and small decorations along the way. Then followed the well-arranged performance by a quartet, assembled online playing musical pieces for the occasion. The quartet was followed by a choir singing separately yet harmoniously, from wherever they were. Then came the sharing from ministers, followed by exchanging of vows and of rings and the signing of the marriage certificate. The ceremony took just more than an hour, and concluded with selfie-taking (so to speak).

In the joy of the moment, though, neither the family nor the guests – nor the bride and groom – cared whether we were there virtually. Not everything was the same – when it came to attire, some of us still chose to dress up for the occasion with formal dress or suit jacket, while others chose to dress casually. People were adapting as they saw fit as we all experienced this together, while apart.

The YouTube broadcasting feature was used, which allowed for viewers all over the world to contribute to the occasion in live time. From the beginning of the online ceremony, we observed many congratulatory wishes and comments beaming through. Family, friends and loved ones from Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto, as well as the United States, Europe, Australia and Asia, left their wishes to the couple. One guest commented that this was the first time that people at a wedding were able to contribute their comments and appreciation of the occasion so instantaneously.

By bringing the wedding online, more people were able to attend, some of whom wouldn’t have been able to come otherwise. For my own family, Montreal is at least a two- to three-hour drive each way; for those observing from Asia, however, that would be at least two days of travel to and from (with much higher fares, if flying has been allowed). Furthermore, these international travellers would have had to quarantine for at least 14 days. That would have made attending this wedding from overseas quite impossible.

At the end of the event, the newlyweds expressed their appreciation to the online wedding planning team, and promised that there will be wedding celebration activities after the restriction order has been lifted. We all looked forward to this day, and ultimately had a positive experience with this online family event. In this case, moving the wedding ceremony online was necessary, practical and sensible, especially in view of pandemic. Time will tell whether online family milestones will be a norm in the future.

Edward Ng, PhD, Vanier Institute on secondment from Statistics Canada

Canadians Turning to Their Screens to Keep Busy During COVID-19 Isolation

Jennifer Kaddatz, Ana Fostik, PhD, and Nathan Battams

April 17, 2020

In some ways, Canadians are making the best of their time in social isolation, according to four weeks of March and April 2020 survey data1 from the Vanier Institute of the Family, the Association for Canadian Studies and Leger.

As of the April long weekend (April 9–12, 2020), half of the country’s population aged 18 or older say they are relaxing “more often” now than they were before the pandemic.

Six in 10 adults are watching movies, television and videos or listening to podcasts more often than before the COVID-19 crisis started. Four in 10 are on social media more frequently.

More than 2 in 10 adults in Canada have increased the amount of time they spend listening to music, reading and playing games during the pandemic.

Half of adults are relaxing more, but some families report decreases in down time

Good news in these challenging times: people in Canada report that they are relaxing more.

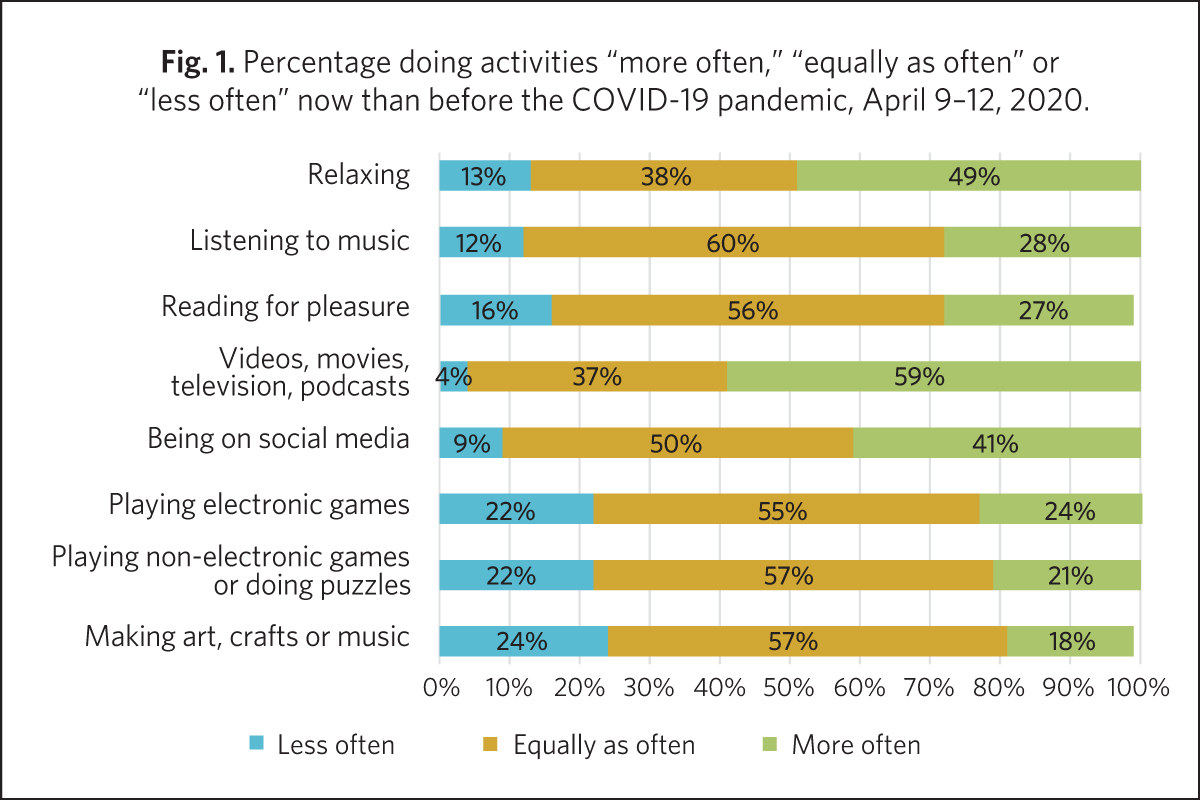

Nearly half (49%) of Canada’s population aged 18 and older say that they are relaxing more often now than they were before the pandemic started, according to survey data from April 9 to 12, 2020 (fig. 1). Another 38% say that they are relaxing equally as often, while 13% say they are relaxing less often.

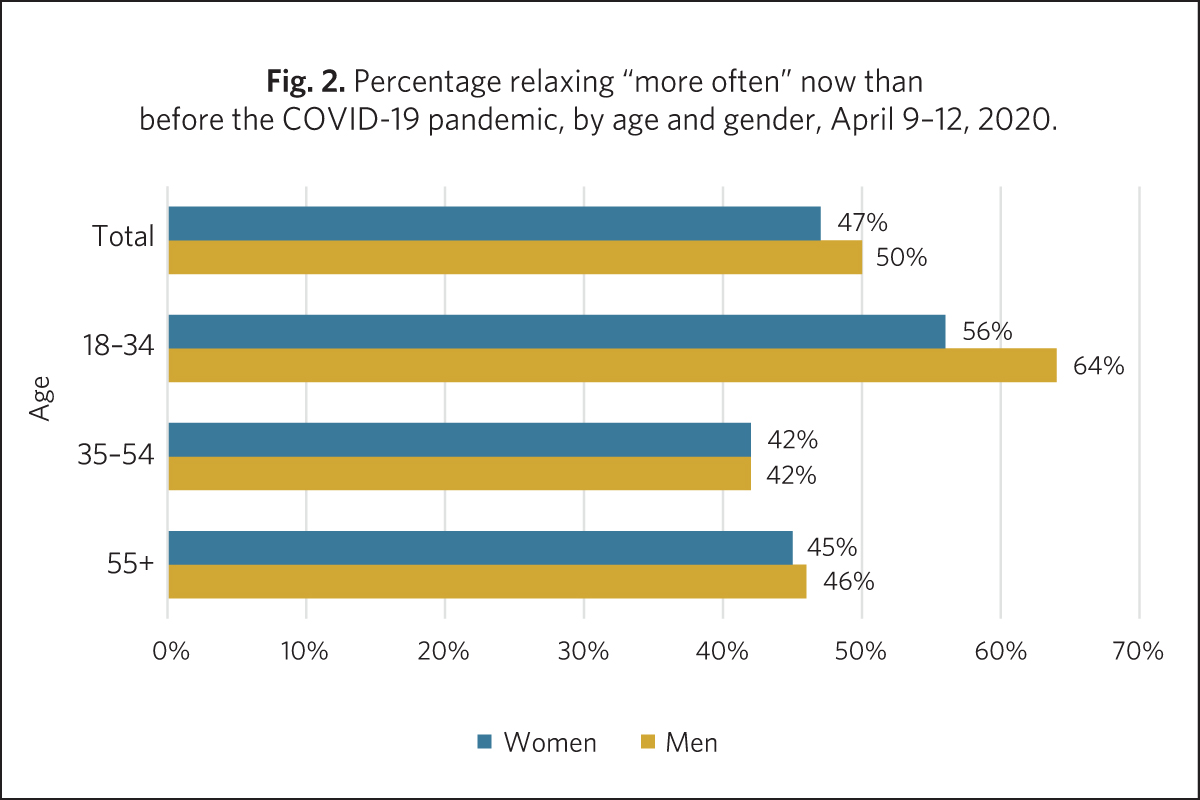

A slightly higher share of men (50%) than women (47%) report relaxing “more often” since the start of the crisis, with most of the difference attributable to younger adults aged 18–34: 64% of young adult males say they are relaxing more often since the start of the pandemic, compared with 56% of young adult females (fig. 2).

Perhaps not surprisingly, adults with young children at home (43%) are less likely than with no children or youth at home (48%) to say that they are relaxing more during the COVID-19 pandemic (fig. 3).

Almost 1 in 4 (24%) of adults who were living in the same home as at least one child under the age of 13 actually reported relaxing less often than before the crisis began.

Three in 10 are listening to music and reading for pleasure more often

About 3 in 10 adults in Canada are listening to music more often now (28%) than before the start of the COVID-19 crisis (fig. 1). This is similar to the share of those saying that they are reading for pleasure more frequently (27%).

According to an analysis of trends over time during COVID-19, there is a significant upwards tendency toward reading, with 23% of the population having said they were reading more often as of March 27–29 compared with 27%, who reported reading more often as of April 9–12.

Women are about as likely as men to spend more time listening to music (27% and 29%, respectively), but a larger share of women than men (29% and 24%) report reading more often since the start of the crisis.

Electronic- or screen-based pastimes are popular and show biggest increases in uptake

Survey data from April 9–12 show that many adults in Canada are turning to their screens to keep busy, as public health measures are keeping them at home.

Of all the activities for which adults were surveyed, “watching movies, television, videos or listening to podcasts” and “being on social media” had highest shares of adults, at 59% and 41% respectively, who say they do these activities “more often” since the start of the COVID-19 crisis (fig. 1).

The share of people saying they had increased the amount of time spent watching movies, television, videos or listening to podcasts was more than double the share of people saying they were reading for pleasure (27%) or listening to music (28%) more often now than in the past.

Furthermore, there appears to be an increasing tendency toward screens as the pandemic continues: 53% of adults in Canada had said they were watching movies, television, videos or listening to podcasts more often in week 2 of the survey (March 27–29) compared with 59% in week 4 (April 9–12).

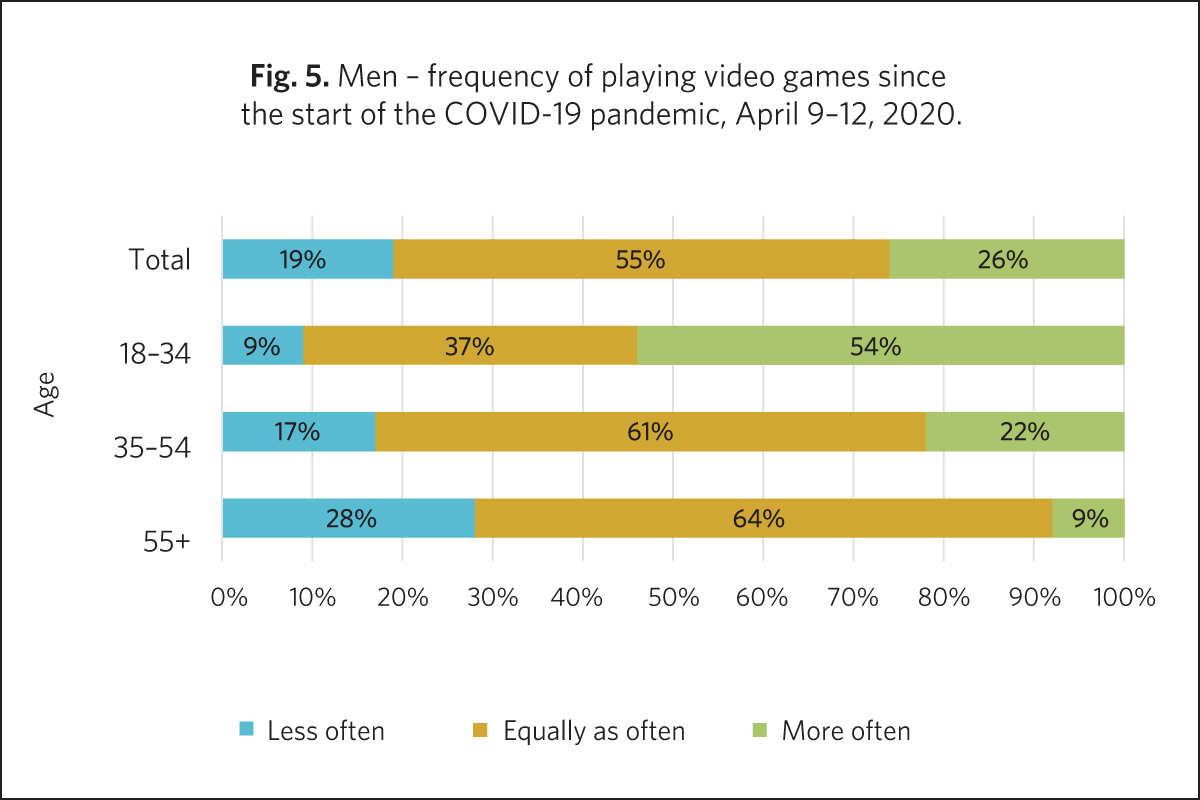

The playing of electronic games also appears to be on the rise: 24% of all adults, or 26% of men and 22% of women, say that they are playing electronic games more now than they did before the pandemic started, according to the April 9–12 survey (figs. 4 and 5). These findings were similar to those published by Statistics Canada for the period of March 29–April 3, based on data collected in a web-based panel, which reported that 22% of all Canadians were now spending more time playing video games.2

Younger adults, especially men, have significantly increased the time they spend playing electronic video games since the start of the pandemic. More than half of men (54%) and one-third of women (36%) aged 18–34 report that they play electronic video games more often now than they did before (figs. 4 and 5).

As well, adults who had at least one child under the age of 13 living in their household (28%) were slightly more likely than those who had only teenagers at home (26%) and those who did not live with children at home (22%) to report playing video games more often since the COVID-19 crisis began.

Women increase time playing board games and doing puzzles, men increase time playing electronic games

Despite the apparent popularity of screen time in general among adults in Canada, the share of those who report having increased their electronic gaming time since the start of the pandemic (24%) is only slightly higher than the share who have increased the amount of time they spend playing board games or doing puzzles (21%) (fig. 1). The share of adults who say that they now undertake these activities “less often,” at 22% and 22%, respectively, is also very similar. However, differences exist by gender and the presence of children and youth in the household.

Similar shares of women say that they play electronic games more often now than they did before the pandemic (22%) say they play non-electronic video games or do puzzles (23%). In comparison, for men there was an 8 percentage point difference in the uptake of the two pastimes, with 26% of men reporting they were electronic gaming more often now and 18% of men saying they were playing board games or doing puzzles more often now than they were before the pandemic.

Furthermore, a slightly larger share of younger women than men have increased the time they spend on non-electronic games or puzzles: about one-third of women (33%) and about one-quarter of men (27%) aged 18–34 report spending more time on this type of activity.

Relatively few older people in Canada report playing board games or doing puzzles more now than before the coronavirus pandemic: about 1 in 10 (9%) men aged 55 or older and 1 in 7 women (15%) of women aged 55 or older.

A significant proportion of women (54%) and men (55%) reported that they play video games “equally as often” as before the COVID-19 pandemic (figs. 4 and 5), though it is important to note that, in some instances, this could just reflect that they didn’t play video games to begin with.

Families with children more often play board games and do arts and crafts

Adults who had at least one child under the age of 13 living in their household (28%) or teenagers at home (22%) are considerably more likely than those who did not live with children (14%) to say that they have been playing non-electronic games and doing puzzles more often now than before the coronavirus pandemic started (fig. 6).

Furthermore, when young kids were in the house, adults are almost twice as likely as those with no children or youth at home to have increased their time spent making arts, crafts or music since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. As of April 9–12, 3 in 10 (31%) adults who lived in a home with at least one child under the age of 13 say that they have been making arts, crafts or music more often since the start of the pandemic, compared with 27% of those with only teenagers at home and 17% of those with no children under 18 at home (fig. 7).

Jennifer Kaddatz, Vanier Institute on secondment from Statistics Canada

Ana Fostik, PhD, Vanier Institute on secondment from Statistics Canada

Nathan Battams is the Communications Manager at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Notes

1. The survey, conducted March 10–13, March 27–29, April 3–5 and April 9–12, 2020, included approximately 1,500 individuals aged 18 and older, interviewed using computer-assisted web-interviewing technology in a web-based survey. The March 27–29, April 3–5 and April 9–12 samples also included booster samples of approximately 500 immigrants. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to gender, age, mother tongue, region, education level and presence of children in the household in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (web panel in this case). However, for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,512 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.52%, 19 times out of 20. Figures may not add up to 100% as a result of rounding.

2. Statistics Canada, “How Are Canadians Coping with the COVID-19 Situation?” Infographics, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-627-X (April 8, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/2z6fm1g.

“Virtual Parenting” After Separation and Divorce

Rachel Birnbaum, PhD, RSW, LLM

Download “Virtual Parenting” After Separation and Divorce (PDF)

The rapid increase in the use of communication technologies, such as text messages, instant messaging, email, social networking sites, Skype, FaceTime and webcams, has provided a variety of new ways for parents to maintain their relationships with their children and manage family responsibilities after separation and divorce. At the same time, the increased use of these methods has also created a new area of discussion and debate about the risks and benefits of this type of “virtual parenting.” Issues such as safety and vulnerability, the ability to use technology, and privacy and confidentiality for the child and each parent are only some of the considerations both for the family justice professionals who recommend virtual contact and for the courts that decide on these types of parent–child contact orders.

Families use technology to maintain ties after separation and divorce

Despite the increasing use of smartphones and online communication technologies, there are few studies about whether this “virtual” contact has an impact on children and their parents after separation and divorce, and what the nature of this impact could be.

Research to date has found that many parents report that using technology has a positive impact because it allows them to be able to stay connected to their children, though some negative aspects were discussed as well, such as sadness about being a “virtual parent,” and the challenges in navigating tensions in keeping the communications private from the other parent and not interfering in the daily activities of the other parent’s household.

One study found that children and youth preferred face-to-face contact and reported difficulties maintaining contact regardless of the type of virtual technology used (e.g. Skype, email, texting, FaceTime). This was due to factors such as issues with phone lines, a lack of immediacy with email contact and time differences as a result of the geographic distances.

The results of these studies highlight both the strengths and challenges parents and children experience in using technology to maintain their contact after separation and divorce. However, they don’t provide a complete picture, as they do not differentiate between parents who communicate well with each other and those who have more conflictual communication resulting from factors such as problem-solving difficulties, a lack of trust and instances where there may be family violence concerns after their separation and divorce.

Diverse perspectives provide fuller insights on “virtual parenting”

A 2018 study provided new insight by incorporating the perspective of legal and mental health professionals, who were surveyed on their views and experiences of using virtual technology after separation and divorce. They found mixed results, particularly with high-conflict families that could not cooperate and in situations where there was interference with the former partner’s parenting time during virtual parent–child contact.

As part of a broader research agenda examining children’s participation in separation and divorce matters, two follow-up studies funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) were performed exploring the use of virtual technology to maintain contact between parents and children after separation and divorce. The first study surveyed 166 family justice professionals (e.g. mental health professionals and lawyers) about their experiences with online technology in general and their views on virtual technology as a means of parent–child contact.

Two key questions provided unique insights into experiences with virtual technology after separation and divorce:

- What do family justice professionals believe are the challenges and benefits regarding the use of technology as a means of parent–child contact?

- What types of conflicts, if any, do adults and children report as a result of using any type of technology for parent–child contact?

The second study explored the same topics from the perspective of parents and children, aiming to shed light on how modern families maintain and manage relationships after separation and divorce.

Research to date has found that many parents report that using technology has a positive impact because it allows them to be able to stay connected to their children.

While the sample sizes were small in both studies, they are the only ones to date that explore the multiple perspectives (e.g. mental health professionals, lawyers, children and parents) using multiple research approaches (e.g. surveys and interviews) to learn more about the views and experiences of children and parents who use virtual communication to maintain contact after separation and divorce.

Children and parents see benefits and challenges associated with virtual contact

One of the recurring themes in the discussion with parents on the benefits was that it can reduce conflict between the parents. As one respondent said, “[I]t cuts down the number of conflicts that can be brought up, which tends to happen when you have swaps…” As with previous research, parents reported that technology has facilitated contact with their children:

“…once we started using this technology [FaceTime], it made all the difference in the world, because she can see me, I can see her, we talk […] if I am away at work, I can show her where I am and make her feel she’s there with me.”

Despite this benefit, parents also reported several sources of conflict, ranging from relatively minor (e.g. when the resident parent interrupts a child’s contact time with the non-resident parent) to more serious concerns about safety (e.g. non-resident parent having access into the resident parent’s home) and confidentiality (one parent said they were “not sure [they like their] child being online and an open communication as there is no real privacy and worry about pictures being taken and then sent somewhere”).

Interview questions about the experiences of children also provided valuable insight into the use of virtual technology as a means of parent–child contact after separation and divorce. Feelings of closeness to the non-resident parent were reported, along with reservations about virtual contact. “While it is really great to see my dad,” one child was reported to have said, “I want to feel him near me as well.” Another echoed this sentiment of longing for the non-resident parent: “One thing I don’t like about this [virtual contact] is I can’t actually see him in person… it’s sad, but good at the same time.”

Using technology to maintain parent–child contact can bring benefits, but also safety and privacy concerns.

Interference with access time and privacy also emerged as themes (“My mom is always asking me how it’s going and how long will I be online with my dad”), as well as availability of the non-resident parent (“I am supposed to call [FaceTime] on Monday and Wednesday; most of the time I can’t really make it, but it creates problems for my dad, who gets upset”).

Family justice professionals see risks and rewards in “virtual contact”

Family justice professionals were also asked to comment about the benefits and challenges of the use of communication technologies as a means of facilitating contact between separated and divorced parents and their children. Below is a snapshot of some of their comments on the risks and rewards:

“Technology can be a valuable tool for facilitating communication and connections when used properly, while at the same time presenting a heightened risk when used improperly and in an unsupervised manner, particularly for young or impressionable children who are caught up in their parents’ conflict deliberately or inadvertently.”

“I think it would be helpful in maintaining a parent–child relationship when one parent lives a significant distance away from where the child resides.”

“Challenge – privacy. Benefit – staying connected in real time.”

“It is a source of evidence about the parent’s ability to cooperate and whether they can reasonably make decisions about the child’s best interests. More rarely, it is also used to establish a prior inconsistent statement. The benefits are significant, since the lack of physical presence can assist clients to calm down in high-conflict cases. At the same time, some clients incorrectly try to use the medium to set up traps for the other parent or engage in what they see is a strategic manoeuvre in litigation.”

Parent and children reports to family justice professionals

To explore the issue of conflict in the parental relationship that may or may not facilitate virtual contact, all family justice professionals were asked to report how often, if ever, their adult and child clients report conflicts (e.g. privacy concerns, safety, confidentiality) during virtual contact such as Skype, FaceTime and WhatsApp.

The parents reported to family justice professionals that the majority of conflicts occur more often as a result of the other parent listening in on their conversation with the child (60%); the other parent alleging that the child is busy doing something else at the designated time (35%); the child not being available for the call at the designated time (41%); and the other parent saying that they do not know how to use or set up the technology (4%).

When asked to identify any other types of conflicts raised by parents, they said that conflicts also occur over the costs of the use of technology and who pays for it; concerns over rural areas where technology is unreliable or too expensive versus urban areas; one parent using the child to harass the non-custodial parent about child support issues; and some parents reporting that they do not want their child using technology because of safety and confidentiality concerns.

The results of this survey are similar to the 2018 study by Saini and Polak, who found that while there were benefits reported by the family justice professionals about using technology to maintain parent–child contact after separation and divorce, there were also challenges such as privacy concerns, safety issues and families experiencing high conflict who may require specific protocols to be put in place to mitigate these concerns.

When surveyed about their child clients, the majority of lawyers and mental health professionals reported that children said they “sometimes” experience conflict over the use of Skype, FaceTime and so on, with the most common conflict being that they’re busy and “do not want to talk at that time” (55%); the child(ren) not having a lot to say to the other parent and the other parent getting upset (45%); and the other parent listening to their conversation during parent–child contact (39%).

When asked to identify any other types of conflicts raised by their child clients, they reported that conflicts also occur over the non-resident parent asking the child questions about the resident parent; the parents arguing with one another during the call; the other parent not being available when the child calls; and the number of text messages and inappropriate content being sent to the child, including both verbal and emotional abuse by the non-resident parent.

Shining light on diverse experiences after separation and divorce

This is the first study incorporating multiple perspectives on virtual technology as a means of parent–child contact after separation and divorce from parents, children and family justice professionals. The findings highlight both risks and rewards depending on the different perspectives (i.e. mother, father, children, mental health professional, lawyer). They also highlight the need for more direction in their family law practices at a time when virtual contact is being increasingly recommended by family justice professionals and the court as a means of parent–child contact after separation.

A number of concerns were highlighted by parents reporting to their lawyers about virtual parent–child contact. These were related to the other parent listening in on the conversation as well as having to be responsible for making sure the child is available at the specified time. In the parent telephone interviews, the greatest concerns centred on safety and the resident parent feeling vulnerable during virtual parent–child contact as well as on privacy issues. That is, parents raised concerns regarding being blocked from access to the technology being used by the non-resident parent and the child, invasion of privacy and feelings of being monitored (e.g. the resident parent as well as the non-resident parent) and the unfettered virtual access to the resident parent’s home as a result of the use of technology. This latter theme raises particular concerns for high-conflict parents and especially for those families in which there may also be issues of domestic violence (e.g. stalking).

Nevertheless, there were also a number of benefits highlighted as a result of virtual contact in both the parental reports to their lawyers as well as in the parent interviews. The greatest benefit raised by each parent is that the child is that it facilitates an ongoing parental relationship and and that it can provide reduced hostilities between the parents, because they have no contact with one another other than organizing the call if the child requires adult assistance.

While it is important to hear diverse perspectives (e.g. children, parents, lawyers, family justice professionals) about this use of technology, more research is needed to determine what impact, if any, there is in relation to factors such as cultural nuances, barriers to using technology (e.g. rural versus urban areas) and the relative burdens and cost (i.e. emotional and financial) to parents providing the technology. It is equally important to examine the safety risks underlying the use of virtual communication tools, especially when high-conflict cases and family violence are of concern.

Our understanding can also benefit from unpacking some of the underlying assumptions about parenting via the virtual world. For example, what does “virtual parenting” mean to children and young people in particular?

Finally, the two studies raise important cautions and considerations for family justice professionals and the court when virtual technology is being recommended as a means of contact after separation. That is, at minimum, consideration should be given to factors such as the child’s age and the length of the contact time; the degree of parental assistance required to facilitate virtual parent–child contact; whether the child has any special needs and resulting degree of parental support required; the type and degree of conflict between the parents; the type and degree of domestic violence concerns (e.g. stalking); financial costs; the separation of aspirational from practical and feasible parenting plans; children’s views on virtual parent–child contact before court orders or agreements are made; and mechanisms to follow up on whether and how virtual contact is working for the children.

Rachel Birnbaum, PhD, RSW, LLM, is a Social Work Professor, cross-appointed between Childhood Studies (Interdisciplinary Programs) and Social Work at King’s University College, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario. She has written, presented and conducted research on many aspects of family justice issues, with a particular emphasis on children’s participation post separation. She thanks the children, parents and family justice professionals who participated in this research for their valuable time in sharing their views and experiences with virtual technology in parenting disputes after separation. Dr. Birnbaum gratefully acknowledges the Social Sciences and Research Humanities Council (SSHRC) in providing funding support to this important and timely area of research.

This article is a reprint of a three-part series featured in The Lawyer’s Daily.

Source information available on the PDF version of this resource.

Published on November 12, 2019

Building Resilience at Home with Distance Coaching

While we all strive to ensure positive mental health and well-being for ourselves and our families, mental health conditions affect most households at some point, directly or indirectly. Children are no exception, with an estimated one in five schoolchildren living with mental health, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders.1

Both early intervention and quality, evidence-based care are essential to supporting children with these conditions and building their resilience. For some families, however, it isn’t always possible to access face-to-face intervention services. Lengthy clinic wait times, fear and/or experience of stigma and long travel distances can make it challenging to access appropriate services.

This can be particularly true for military families, in which a parent may have unpredictable schedules that often involve a greater amount of travel, separation, routine disruptions, transitions and overall stress than their civilian counterparts. Due to their high mobility and frequent moves, military families also commonly experience difficulties maintaining continuity of care for their children.2

Flexibility can facilitate mental health care for families

Clinic-based mental health services offer a variety of programs and supports to youth, but many lack the flexibility that families require to support these children while managing other family and work responsibilities. Children’s school schedules often don’t align with available mental health services, and repeated absences due to the need to attend regular appointments at a clinic can have an impact on children’s academic performance and their social relationships with friends and peers.

It may also be difficult or impossible for many parents to take the necessary time off work to bring a child to face-to-face appointments, either because they lack the necessary flexibility at work or because doing so would incur financial hardship. Nearly 7 in 10 couple families with at least one child under 16 have two employed parents, and in three-quarters of these couples, both parents work full-time.3 For single-parent families, the impact of missing work to accommodate appointments can be particularly difficult. Flexibility can be all the more important when seeking support for their children in military families, which often experience high mobility and deployments.

The Strongest Families Institute provides family-centred mental health care

Founded in 2011, the Strongest Families Institute (SFI) is a not-for-profit corporation designed to provide flexible, evidence-based and stigma-free mental health support to children customized to their needs and family realities. Based on six years of research at the Centre for Research in Family Health at the IWK Health Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia, SFI programs and modules are now accessible across the country. SFI has been nationally recognized for social benefits by the Mental Health Commission of Canada (2012) and was the recipient of the Ernest C. Manning Encana Principal Award (2013).

SFI programs use a family-centred approach, directly engaging and involving family members throughout the process. Families can play a powerful role in facilitating quality mental health care because of their familiarity with the child’s circumstances. They also have a unique ability to provide valuable feedback to service providers throughout the engagement process.

Developing skills to build resilience… from a distance

SFI programs are focused on skill-based learning that fosters mental health and resilience skills through the use of psychologically informed educational modules that help families manage behavioural conditions or difficulties (e.g. not listening, temper or anger outbursts, aggression, attention deficits or hyperactivity) and anxiety (e.g. separation, generalized, social, specific fears).

SFI employs a unique distance coaching approach, utilizing technology to directly support families over the phone and the Internet in the comfort, privacy and convenience of their own home.4 Research has shown that distance coaching can result in significant diagnosis decreases among children with disruptive behaviour or anxiety conditions.5

“[My coach] has taught me a lot of skills that I was not aware of – especially in the conditions of the ever-changing military family life situation – and helped us deal with a lot of challenges. [My child] is more patient and approachable now. He knows how to deal with stress when his father is away [deployed]. His grades and behaviour at school have improved as well, he has fewer outbursts and the teachers have noticed the difference as well.”

– Parent of a 9-year-old participant in the Active Child program (Behaviour)

SFI’s Parenting the Active Child Program focuses on child behaviour for ages 3 to 12. In this program, parents and their children work together to create structured plans to help manage specific challenges a child may experience during particular times or activities. For example, parents and children can work together to develop a plan to make outings such as a trip to the grocery store or long trip in the car more enjoyable by using program skills. Through this simple but structured and guided approach, parents together with their children and the coach can work toward and reward good behaviour. By using the family home as a base for learning rather than a clinic setting, many of the issues of stigma are avoided. Families receive a series of written materials and skill demonstration videos, delivered either through handbooks or by smart-website technology, which teach one new skill per week to implement as part of their daily living activities.

The SFI anxiety program for 6- to 17-year-olds, Chase Worries Away, helps family learn life skills to defeat worries such as separation anxiety, performance issues, social anxiety and specific fears that are commonly related to the challenges of military life. SFI also runs a program for children ages 5 to 12 called Dry Nights Ahead, which helps with nighttime bedwetting.

Coaches ensure stability and guidance throughout the program

Children and families are supported and guided throughout the SFI programs by highly trained and monitored coaches. These coaches engage in structured weekly telephone calls that follow protocolized scripts, complementing the material families receive. During each session, the family’s coach reviews the skill that has been developed throughout the week and uses evidence-based strategies, such as role-playing and verbal modelling, to practise the skills and assess progress.

Schedules are flexible and customizable to accommodate families regardless of where they are located or where they move. This flexibility and focus on distance coaching can be particularly valuable for military families, bridging the geographical divide during separations resulting from postings so that the continuum of care is maintained. Moreover, during a posting, coaches help the families plan for the transition and they remain available during and after to encourage the maintenance of skills. This focus on planning supports families during potentially disruptive transitions, such as during a change of school or daycare.

The coach can be a familiar, centralized contact/support for the family, regardless of the move location. Coaches have high military literacy – understanding of the unique experiences of military families and the “military life stressors” that can have an impact on military families, such as high mobility, extended and/or unexpected separation and risk. Care and support is customized to the realities and needs of each family.

“[The program] helped me quite a bit, especially in everything anxiety, I still have other issues, but in terms of anxiety it has become less of a problem for me, socially, being independent, things I wouldn’t have done before, school stress has reduced quite a bit. They were the main things I was focused toward, and this has decreased stress for me.”

– 16-year-old participant in the Chase Worries Away program (Anxiety)

Transferable learning: Flexible support for diverse and unique families

SFI programs have demonstrated success, with families reporting high satisfaction. Rigorous testing and randomized trials show positive outcomes, with lasting effects one year later, targeting mild and moderate conditions. Programs have been found to have an 85% or better success rate in overcoming the child’s presenting problems, with an attrition rate of less than 10%. Data shows a strong impact on strengthening family relationships, parental mood/stress scores and child academic performance.

Families and their children are unique, and there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution to manage mental health or behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders. Flexibility in SFI program design and availability can enhance the use and effectiveness of mental health supports, since families can receive support outside of traditional clinic settings and schedules. By using distance coaching and continued family support through structured calls with coaches, families engaged with SFI can receive care that is flexible, effective and respectful of their experiences and realities.

About the Strongest Families Institute

The Strongest Families Institute (SFI) is a national, not-for-profit organization that delivers distance, evidence-based programs to children and families who face issues impacting mental health and well-being. Founded in 2011, SFI seeks to provide timely delivery of services to families when and where they are needed by using technology, research and highly skilled staff.

Over the years, SFI has formed many partnerships to improve its services. Some of these partnerships have helped them deliver services to military and Veteran families, including Military Family Services – Ottawa, Bell True Patriot Love Foundation (Bell Let’s Talk) and a project collaboration with CIMVHR.

Notes

- Ann Douglas, Parenting Through the Storm (Toronto: HarperCollins, 2015).

- Heidi Cramm et al., “The Current State of Military Family Research,” Transition (January 19, 2016).

- Sharanjit Uppal, “Employment Patterns of Families with Children,” Insights on Canadian Society (June 24, 2015), Statistics Canada catalogue no. 75-006-X, http://bit.ly/1Nen7gR.

- Patricia Lingley-Pottie and Patrick J. McGrath, “Telehealth: A Child-Friendly Approach to Mental Health Care Reform,” Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 14 (2008): 225–26, doi:10.1258/jtt.2008.008001.

- Patrick J. McGrath et al., “Telephone-Based Mental Health Interventions for Child Disruptive Behavior or Anxiety Disorders: Randomized Trials and Overall Analysis,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 50, no. 11 (2011): 1162–72, doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.013.

The Online Lives of Canadian Youth

Matthew Johnson

November 2–6 is Media Literacy Week, an event that highlights the importance of teaching children and teens digital and media literacy skills to ensure their interactions with media are positive and enriching. In this week’s blog post, Matthew Johnson from MediaSmarts discusses the online behaviour of Canadian youth and the role of parents in their lives on the Web.

Digital natives. Tech-savvy. Narcissistic. Innovative. Mean. There are a lot of assumptions about kids online, but the labels we use are often misleading and out of step with what young people are actually doing with networked technologies. In order to better understand the online lives of Canadian children and youth, MediaSmarts – a Canadian not-for-profit charitable organization for digital and media literacy – conducted an extensive national survey of students in Grades 4 through 11 as part of the Young Canadians in a Wired World research series, which began in 2000.

It goes without saying that eight years is a long time on the Internet. Between 2005, when MediaSmarts published Phase II of its Young Canadians in a Wired World research, and 2013, when it conducted the national student survey for Phase III, the Internet changed almost beyond recognition: online video, once slow and buggy, became one of the most popular activities on the Web, while social networking became nearly universal among both youth and adults.

Young people’s online experiences have changed as well, so MediaSmarts surveyed 5,436 Canadian students in Grades 4 through 11, in classrooms in every province and territory, to find out how. The first report drawn from this survey, Life Online, focuses on what youth are doing online, what sites they are going to and their attitudes toward online safety, household rules on Internet use and unplugging from digital technology.

Nearly all youth have access to the Internet

One finding, which is unlikely to be a surprise, is that nearly all youth are going online. In fact, 99% of students surveyed have access to the Internet outside of school using a variety of devices. The biggest change since the last survey is the proliferation of mobile and portable devices, such as tablets, smartphones and web-enabled MP3 players, which give youth constant – and often unsupervised – online access. In the previous Young Canadians in a Wired World report, in 2005, the majority of students accessed the Internet through shared desktop computers at home (which were often kept in the family room or kitchen so parents could keep an eye on the online activities of their children), whereas now portable and personal networked devices, such as tablets and smartphones, are the primary access point for many of these students.

Portable, private access to the Internet was found to increase with age, while reliance on shared computers has decreased: 64% of Grade 4 students report using a shared family computer to go online outside of school, but this drops to 37% by Grade 11. Ownership of cellphones and smartphones, on the other hand, is reported by 24% of students in Grade 4, 52% of students in Grade 7 and 85% of students in Grade 11. Perhaps not surprisingly, ownership of these devices is correlated with family affluence: a greater proportion of more-affluent students compared with medium-affluent students report access to portable computers (74% vs. 61%), cellphones (49% vs. 41%) and game consoles (45% vs. 38%).

Not only are students getting connected, they are staying connected: more than one-third of students who own cellphones say they sleep with their phones in case they get calls or messages during the night. This is true of both girls and boys (39% and 37%, respectively, of those who own cellphones). The trend increases across grades to peak at just over half (51%) of Grade 11 students, but one-fifth of all students in Grade 4 also report that they do the same.

Students are well aware that they are frequently “plugged in”: 40% of girls and 31% of boys report worrying that they spend too much time online. When asked how they would feel if they could not go online for anything other than school or work for a week, just under half (49%) say they would be upset or unhappy. Interestingly, English-language students outside of Quebec are more likely to be upset than French-language students in Quebec (51% vs. 40%). However, 46% of all students indicate they would not care one way or the other and 5% report that they would be relieved or happy to go offline.

Many students try to balance their online and offline activities, saying that they sometimes choose to go offline in order to spend more time with friends and family (77%), go outside or play a game or sport (71%), read a book (44%) or just enjoy some solitary quiet time (45%). Only 4% say that they never choose to go offline to do any of these things.

Youth go online to learn, play games and socialize

What are Canadian youth doing when they are online? For many, the Internet is a tool for learning and sharing information: half (49%) of students in all grades have gone online to find information about news and current events and half of students in Grades 7–11 have sent links to news stories or current events to others. However, relatively few have participated in online debates, either by posting comments on a news site (71% of Grades 7–11 have never done so) or joining an activist group (65% of all grades have never done so).

Students report looking for information on the Internet on sensitive topics, such as mental health issues, sexuality, physical health issues and relationship problems.

Children and youth are not just interested in learning about news and current events, however. Many report going online to learn about health and well-being, whether it’s to learn about physical health (20% of girls and 16% of boys), mental health (14% of girls and 9% of boys) or relationship problems (18% of girls and 9% of boys). The percentage of students who use the Internet as an information source increases from Grade 4 through to Grade 11.

Compared with students in younger grades, a higher percentage of students in Grades 7–11 report looking for information on more sensitive topics, such as mental health issues, sexuality, physical health issues and relationship problems. However, nearly one-quarter (22%) of students report that they do not use the Internet to find information about any of these things. Close to one-third of students report having gone online to ask an expert (30%) or other kids (33%) for advice about a personal problem, although only a small percentage report frequently doing so.

Two-thirds of students report that they play online games, with this activity being significantly more popular among boys (71%) than girls (47%). Unlike other online activities, which increase with age, the proportion of students who report playing online games decreases over time, from a high of 77% in Grade 5 to a low of 42% in Grade 10.

Not surprisingly, social networking is also a popular activity, particularly among older students in the survey. The increased participation in social media-related activities is consistent with developmental literature that suggests that social connection becomes more important as young people move from childhood to their teen years. Between Grade 4 and Grade 11, reading others’ profiles increases from 18% to 72%, tweeting increases from 5% to 42%, following friends/family on Twitter rises from 8% to 39%, posting on one’s own profile rises from 19% to 50% and following celebrities on Twitter rises from 5% to 32%. Girls are more likely than boys to report using social media to communicate with family and friends (45% posted on their own social networking site, compared with 36% of boys).

Many parents regulate the online lives of their children

Parents have continued to be involved in their children’s online lives, with 84% of surveyed students reporting that they have household rules to follow regarding their online activity. The most common rules are about posting contact information online (55%), talking to strangers online or on a cellphone (52%), avoiding certain sites (48%), treating people online with respect (47%) and getting together with online acquaintances (44%).

There have been changes involving household rules regarding online activities since the 2005 survey. Although MediaSmarts’ 2012 focus groups with parents and youth showed parents were more concerned than ever about what youth were doing online, the average number of household rules has actually declined since 2005. For example, in the earlier survey, 74% of students had a rule at home about meeting people whom they first met online, compared with only 44% today. Regarding personal information, 69% of students in 2005 had a rule about giving personal information online, whereas 55% in 2013 had a rule about posting contact information.

84% of surveyed students report that they have household rules to follow regarding their online activity.

Consistent with our previous research, household rules have a significant positive impact on what students do online, reducing risky behaviours such as posting contact information, visiting gambling sites, seeking out online pornography and talking to strangers online. In general, though, the number of household rules takes a sharp dive after Grade 7 and at all ages girls are more likely to report having rules about their online activities than boys. For example, girls are more likely than boys to report having online rules about talking to strangers (61% of girls vs. 40% of boys), getting together with someone they have met online (52% vs. 35%), telling their parents about anything that makes them uncomfortable online (46% vs. 30%) and treating people online with respect (54% vs. 40%).

The greater number of rules placed on girls may be based on a sense that girls are generally more vulnerable, but it may also relate to the fact that the Internet is a very different place for girls than for boys. Girls are less likely to agree with the statement “The Internet is a safe place for me” and more likely to agree that “I could be hurt if I talk to someone I don’t know online.” Despite these differences, both boys and girls feel confident in their ability to look after themselves, with nine out of 10 agreeing with the statement “I know how to protect myself online.”

Youth learn about online life from a variety of sources

Students do see their parents as a valuable resource for learning about the Internet: nearly half (45%) of students say they have learned about issues such as cyberbullying, online safety and privacy management at home. However, parents aren’t their only source of information about online issues, with students also reporting learning about these issues from teachers (41%), friends (18%) and online sources (19%). As students get older, they are less likely to report having learned about these issues from parents and more likely to learn from teachers: for example, students in Grades 4–6 were more likely to report having learned about how to be safe online from parents (75%) than teachers (50%). A worrying number of students have not learned about these topics from any source. For example, more than half of students in Grades 4–6 have not learned any strategies for authenticating online information either at home or at school.

Life Online has raised many issues that call for more in-depth study. However, the evidence is clear at this early stage that despite their confidence with digital tools – or perhaps because of it – Canadian youth, and particularly elementary-aged children, need instruction in digital literacy skills, and parents and teachers need to be given tools and resources to help them provide that instruction.

This article was originally featured in Transition magazine in fall 2013 (Vol. 43, No. 3).

Matthew Johnson is Director of Education at MediaSmarts, Canada’s centre for digital and media literacy.

For resources and information about digital and media literacy, visit the MediaSmarts and Media Literacy Week websites.