Simona Bignami is a demographer specializing in quantitative methods and family dynamics. Broadly speaking, she is interested in the relationship between social influence, family dynamics, and demographic outcomes and behaviours, and the extent to which empirical evidence helps us understand this relationship. Her most recent work focuses on migrants’ and ethnic minorities’ family dynamics, attempting to improve their measurement with innovative data and methods, and to understand their role for demographic and health outcomes. Her research on these topics takes a comparative perspective, and spans from developing to developed country settings. Although her research is quantitative, she has experience collecting household survey data and conducting qualitative interviews and focus groups in different settings.

Topic: One-parent families

Robin McMillan

Robin McMillan has spent her career of over 30 years working in the early learning sector. For the first eight years, she worked as an Early Childhood Educator with preschool children. She left the front line to develop resources for practitioners at the Canadian Child Care Federation (CCCF). She has been with the CCCF since 1999 and worked her way from Project Assistant to Project Manager to her present role as Innovator of Projects, Programs and Partnerships. Highlights of her career with CCCF have been managing over 20 national and international projects, including a CIDA project in Argentina and presenting a paper with the Honourable Senator Landon Pearson to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva, Switzerland.

Robin served as a board member on the Ottawa Carleton Ultimate Association for two years, as well as participated in organizing numerous local charity events. She founded and facilitated a local parent support group, Ottawa Parents of Children with Apraxia, and a national group, Apraxia Kids Canada. She is married and has a 17-year-old son with a severe speech disorder, childhood apraxia of speech, and a mild intellectual disability, which launched her into the world of parent advocacy. She was the recipient of the Advocate of the Year Award in 2010 from the Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America.

About the Organization: We are the community in the early learning and child care sector in Canada. Professionals and practitioners from coast to coast to coast belong in our community. We give voice to the deep passion, experience, and practice of Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) in Canada. We give space to excellent research in policy and practice to better inform service development and delivery. We provide leadership on issues that impact our sector because we know we are making a difference in the lives of young children—our true purpose, why we exist—to make a difference in these lives. What gets talked about, explored, and shared in our community is always life changing, and we know that. We are a committed, passionate force for positive change where it matters most—with children.

Maude Pugliese

Maude Pugliese is an Associate Professor at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (Université du Québec) in the Population Studies program and holds the Canada Research Chair in Family Financial Experiences and Wealth Inequality. She is also the scientific director of the Partenariat de recherche Familles en mouvance, which brings together dozens of researchers and practitioners to study the transformations of families and their repercussions in Quebec. In addition, she is the director of Observatoire des réalités familiales du Québec/Famili@, a knowledge mobilization organization that diffuses the most recent research on family issues in Quebec to a broad public in accessible terms. Her current research work focuses on the intergenerational transmission of wealth and of money management practices, gender inequalities in wealth and indebtedness, and how new intimate regimes (separation, repartnering, living apart together, polyamory, etc.) are transforming ideals and practices of wealth accumulation.

Andrea Doucet

Andrea Doucet is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Gender, Work, and Care, Professor in Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University, and Adjunct Professor at Carleton University and the University of Victoria (Canada). She has published widely on care/work policies, parental leave policies, fathering and care, and gender divisions and relations of paid and unpaid work. She is the author of two editions of the award-winning book Do Men Mother? (University of Toronto Press, 2006, 2018), co-author of two editions of Gender Relations: Intersectionality and Social Change (Oxford, 2008, 2017), and co-editor of Thinking Ecologically, Thinking Responsibly: The Legacies of Lorraine Code (SUNY, 2021). She is currently writing about social-ecological care and connections between parental leaves, care leaves, and Universal Basic Services. Her recent research collaborations include projects with Canadian community organizations on young Black motherhood (with Sadie Goddard-Durant); feminist, ecological, and Indigenous approaches to care ethics and care work (with Eva Jewell and Vanessa Watts); and social inclusion/exclusion in parental leave policies (with Sophie Mathieu and Lindsey McKay). She is the Project Director and Principal Investigator of the Canadian SSHRC Partnership program, Reimagining Care/Work Policies, and Co-Coordinator of the International Network of Leave Policies and Research.

Liv Mendelsohn

Liv Mendelsohn, MA, MEd, is the Executive Director of the Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence, where she leads innovation, research, policy, and program initiatives to support Canada’s caregivers and care providers. A visionary leader with more than 15 years of experience in the non-profit sector, Liv has a been a lifelong caregiver and has lived experience of disability. Her experiences as a member of the “sandwich generation” fuel her passion to build a caregiver movement in Canada to change the way that caregiving is seen, valued, and supported.

Over the course of her career, Liv has founded and helmed several organizations in the disability and caregiving space, including the Wagner Green Centre for Accessibility and Inclusion and the ReelAbilities Toronto Film Festival. Liv serves as the chair of the City of Toronto Accessibility Advisory Committee. She has received the City of Toronto Equity Award, and has been recognized by University College, University of Toronto, Empowered Kids Ontario, and the Jewish Community Centres of North America for her leadership. Liv is a senior fellow at Massey College and a graduate of the Mandel Institute for Non-Profit Leadership and the Civic Action Leadership Foundation DiverseCity Fellows program.

About the Organization: The Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence supports and empowers caregivers and care providers, advances the knowledge and capacity of the caregiving field, and advocates for effective and visionary social policy, with a disability-informed approach. Our expertise and insight, drawn from the lived experiences of caregivers and care providers, help us campaign for better systems and lasting change. We are more than just a funder; we work closely with our partners and grantees towards shared goals.

Barbara Neis

Barbara Neis (PhD, C.M., F.R.S.C.) is John Lewis Paton Distinguished University Professor and Honorary Research Professor, retired from Memorial University’s Department of Sociology. Barbara received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Toronto in 1988. Her research focuses broadly on interactions between work, environment, health, families, and communities in marine and coastal contexts. She is the former co-founder and co-director of Memorial University’s SafetyNet Centre for Occupational Health and Safety and former President of the Canadian Association for Work and Health. Since the 1990s, she has carried out, supervised, and supported extensive collaborative research with industry in the Newfoundland and Labrador fisheries including in the areas of fishermen’s knowledge, science, and management; occupational health and safety; rebuilding collapsed fisheries; and gender and fisheries. Between 2012 and 2023, she directed the SSHRC-funded On the Move Partnership (www.onthemovepartnership.ca), a large, multidisciplinary research program exploring the dynamics of extended/complex employment-related geographical mobility in the Canadian context, including its impact on workers and their families, employers, and communities.

Deborah Norris

Holding graduate degrees in Family Science, Deborah Norris is a professor in the Department of Family Studies and Gerontology at Mount Saint Vincent University. An abiding interest in the interdependence between work and family life led to Deborah’s early involvement in developing family life education programs at the Military Family Resource Centre (MFRC) located at the Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Halifax. Insights gained through conversation with program participants were the sparks that ignited a long-standing commitment to learning more about the lives of military-connected family members—her research focus over the course of her career to date. Informed by ecological theory and critical theory, Deborah’s research program is applied, collaborative, and interdisciplinary. She has facilitated studies focusing on resilience(y) in military and veteran families; work-life balance in military families; the bi-directional relationship between operational stress injuries and the mental health and wellbeing of veteran families; family psychoeducation programs for military and veteran families; and the military to civilian transition. She has collaborated with fellow academic researchers, Department of National Defense (DND) scientists, Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) personnel, and others. Recently, her research program has expanded to include an emphasis on the impacts of operational stress on the families of public safety personnel.

Shelley Clark

Shelley Clark, James McGill Professor of Sociology, is a demographer whose research focuses on gender, health, family dynamics, and life course transitions. After receiving her PhD from Princeton University in 1999, Shelley served as program associate at the Population Council in New York (1999–2002) and as an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago (2002–2006). In the summer of 2006, she joined the Department of Sociology at McGill, where in 2012 she became the founding Director of the Centre on Population Dynamics. Much of her research over two decades has examined how adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa make key transitions to adulthood amid an ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Additional work has highlighted the social, economic, and health vulnerabilities of single mothers and their children in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently she has embarked on a new research agenda to assess rural and urban inequalities and family dynamics in the United States and Canada. Her findings highlight the diversity of family structures in rural areas and the implications of limited access to contraception on rural women’s fertility and reproductive health.

Isabel Côté

Isabel Côté is a full professor in the department of social work at Université du Québec en Outaouais. She holds the Canada Research Chair on Third-Party Reproduction and Family Ties, is a member of Partenariat Famille en mouvance (a research partnership on the changing family) and of the Réseau québécois en études féministes (RéQEF) (a Quebec network for feminist studies). Her research program aims to develop a global understanding of third-party reproduction that brings together the viewpoints of all parties, including parents, donors, surrogates, the children conceived this way, and the extended families. Using innovative qualitative methodologies, her work draws on the theoretical contributions of sociology of the family, kinship anthropology, and feminist and LGBTQ studies, and takes a fresh look at contemporary family realities. In an innovative way, her work considers children as full agents in the construction of knowledge about families created thanks to third-party reproduction. Lastly, the results of her work provide material, based on empirical data, to inform the social debate about the issues raised by third-party reproduction while also suggesting courses of action to better support the wellbeing of the people concerned.

Lindsey McKay

Lindsey McKay is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, British Columbia. She is a feminist sociologist/political economist of care work, health and medicine, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Social justice motivates her research and teaching. She has published in peer-reviewed journals and public platforms on parental leave inequity, organ donation, and curriculum and pedagogy. She is a Co-Investigator in the SSHRC funded Reimagining Care/Work Policies project with a focus on parental leave.

Families Count 2024: Family Structure

Family Structure is the first section of a larger report that will also explore family work, family identity, and family wellbeing.

Then and Now: A 30-Year Look at Family Structures in Canada

Families in Canada Interactive Timeline

Today’s society and today’s families would have been difficult to imagine, let alone understand, a half-century ago. Data shows that families and family life in Canada have become increasingly diverse and complex across generations – a reality highlighted when one looks at broader trends over time.

But even as families evolve, their impact over the years has remained constant. This is due to the many functions and roles they perform for individuals and communities alike – families are, have been and will continue to be the cornerstone of our society, the engine of our economy and at the centre of our hearts.

Learn about the evolution of families in Canada over the past half-century with our Families in Canada Interactive Timeline – a online resource from the Vanier Institute that highlights trends on diverse topics such as motherhood and fatherhood, family relationships, living arrangements, children and seniors, work–life, health and well-being, family care and much more.

View the Families in Canada Interactive Timeline.*

Full topic list:

- Motherhood

o Maternal age

o Fertility

o Labour force participation

o Education

o Stay-at-home moms

- Fatherhood

o Family relationships

o Employment

o Care and unpaid work

o Work–life

- Demographics

o Life expectancy

o Seniors and elders

o Children and youth

o Immigrant families

- Families and Households

o Family structure

o Family finances

o Household size

o Housing

- Health and Well-Being

o Babies and birth

o Health

o Life expectancy

o Death and dying

View all source information for all statistics in Families in Canada Interactive Timeline.

* Note: The timeline is accessible only via desktop computer and does not work on smartphones.

Published February 8, 2018

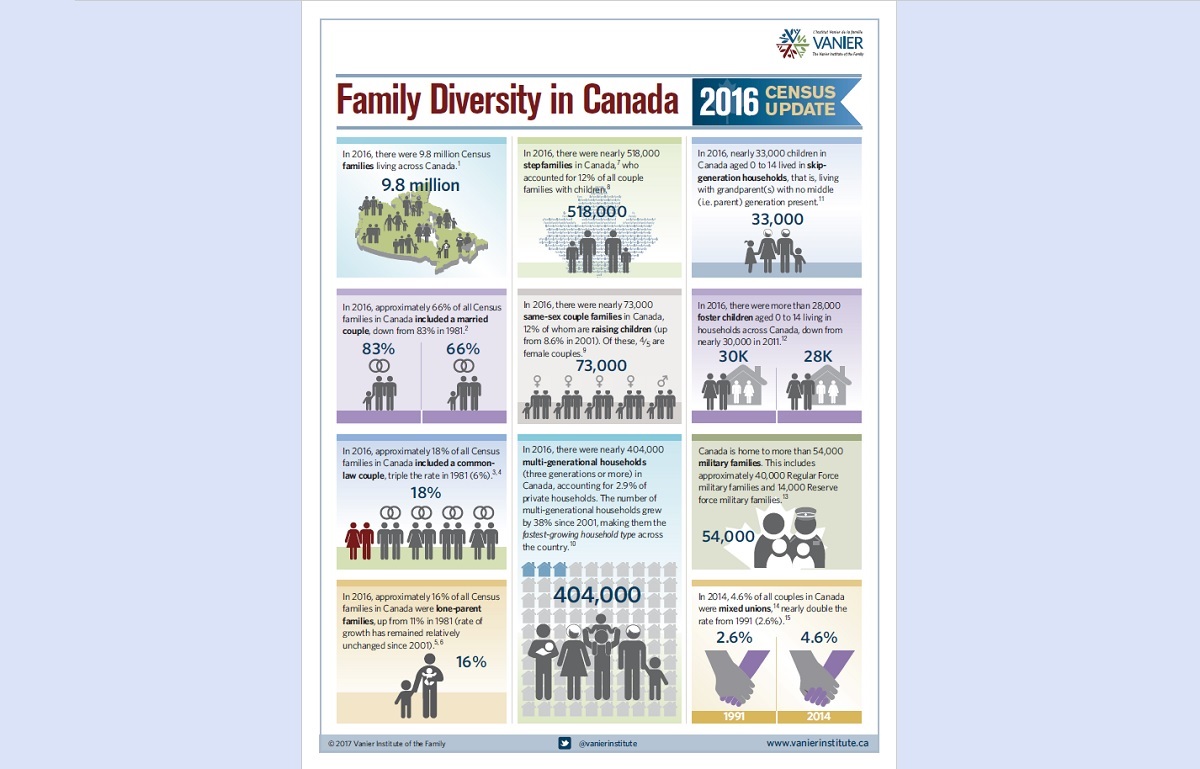

Infographic: Family Diversity in Canada (2016 Census Update)

Download the Family Diversity in Canada (2016 Census Update) infographic

The Vanier Institute of the Family has now been exploring families and family life in Canada for more than 50 years. Throughout this half-century of studying, discussing and engaging with families from coast to coast to coast, one thing has been clear from the outset: families in Canada are as diverse as the people who comprise them.

This has always been the case, whether one examines family structures, family identities, family living arrangements, family lifestyles, family experiences or whether one looks at the individual traits of family members such as their ethnocultural background, immigration status, sexual orientation or their diverse abilities.

These parents, children, grandparents, great-grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, cousins, friends and neighbours all make unique and valuable contributions to our lives, our workplaces and our communities. As former Governor General of Canada, His Excellency The Right Honourable David Johnston, said at the Families in Canada Conference 2015, “Families, no matter their background or their makeup, bring new and special patterns to our diverse Canadian tapestry.”

Using new data from the 2016 Census, the Vanier Institute has published an infographic on family diversity in Canada.

Highlights include:

- 66% of families in Canada include a married couple, 18% are living common-law, and 16% are lone-parent families – diverse family structures that continuously evolve.

- 518,000 stepfamilies live across the country, accounting for 12% of couples with children under age 25.

- 404,000 households in Canada are multi-generational,1 and nearly 33,000 children live in skip-generation households.2

- 1.7M people in Canada reported having an Aboriginal identity (58.4% First Nations, 35.1% Métis, 3.9% Inuit, 1.4% other Aboriginal identity, 1.3% more than one Aboriginal identity).

- 360,000 couples in Canada are mixed unions,3 accounting for 4.6% of all married and common-law couples.

- 73,000 same-sex couples were counted in the 2016 Census, 12% of whom are raising children.

- 54,000 military families live in Canada, including 40,000 Regular Force military families and 14,000 Reserve force military families.

Download the Family Diversity in Canada (2016 Census Update) infographic.

This bilingual resource is a perpetual publication, and will be updated periodically as new data emerges (older versions are available upon request). Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter to find out about updates, as well as other news about publications, projects and initiatives from the Vanier Institute.

Notes

- Containing three or more generations.

- Living with grandparent(s) with no middle (i.e. parent) generation present.

- Statistics Canada defines a mixed union as “a couple in which one spouse or partner belongs to a visible minority group and the other does not, as well as a couple in which the two spouses or partners belong to different visible minority groups.” Link: http://bit.ly/2tZvrSr.

Timeline: Fifty Years of Men, Work and Family in Canada

Over the past half century, fatherhood in Canada has undergone a significant evolution as men are increasingly sharing the “breadwinning” role, embracing caring responsibilities and integrating their responsibilities at home, at work and in their communities.

To explore these trends and the social, economic, cultural and environmental contexts that shape – and are shaped by – fatherhood and family relationships, we’ve created a 50-year timeline for Father’s Day 2016. Some highlights include:

- More fathers are taking time off to care for their newborn children. More than one-quarter (27%) of all recent fathers in Canada reported in 2014 that they took (or intended to take) parental leave, up from only 3% in 2000.

- The number of “stay-at-home” fathers is on the rise. Fathers accounted for approximately 11% of stay-at-home parents in 2014, up from only 1% in 1976.

- Fathers of young children are absent from work more frequently for family-related reasons. Fathers of children under the age of 5 report missing an average 2.0 days of work in 2015 due to personal or family responsibilities, up from 1.2 days in 2009.

- Fewer “lone fathers” are living in low income. In 2008, 7% of persons in lone-parent families headed by men lived in low income, down from 18% in 1976.

- Fathers are increasingly helping with housework. Men who report performing household work devoted an average 184 minutes on these tasks in 2010, up from 171 minutes in 1998.

- Fathers with flex are more satisfied with their work–life balance. More than eight in 10 (81%) full-time working fathers with children under age 18 who have a flexible schedule reported in 2012 being satisfied with their work–life balance, compared with 76% for those without a flexible schedule.

- A growing number of children find it easier to talk to dad. In 2013–2014, 66% of 11-year-old girls and 75% of boys the same age say they find it easy to talk to their father about things that really bother them, up from 56% and 72%, respectively, two decades earlier.

This bilingual resource is a perpetual publication, and it will be updated periodically as new data emerges. Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter to find out about updates, as well as other news about publications, projects and initiatives from the Vanier Institute.

Enjoy our new timeline, and happy Father’s Day to Canada’s 8.6 million dads!

Download the Fifty Years of Men, Work and Family in Canada timeline.

Infographic: Family Diversity in Canada 2016

International Day of Families is approaching on May 15, a special day to recognize the importance of family to communities across the globe. Parents, children, grandparents, great-grandparents, aunts, uncles, siblings, cousins and the friends and neighbours we care for (and who care for us) all make unique and valuable contributions to our lives, our workplaces and our communities.

As we reflect on Canada’s 9.9 million families, one thing that’s clear is that there’s no such thing as a cookie-cutter family. Families are as diverse and unique as the people who comprise them, and they are all an essential part of Canada’s family landscape.

For this year’s International Day of Families, we’ve created an infographic providing a “snapshot” of modern families in Canada that highlights some of the many ways families are diverse:

- 67% of families in Canada are married-couple families, 17% are living common-law, and 16% are lone-parent families – diverse family structures that continuously evolve

- 464,000 stepfamilies live across the country, accounting for 13% of couples with children

- 363,000 households contain three or more generations, and there are also approximately 53,000 “skip-generation” homes (children and grandparents with no middle generation present)

- 1.4 million people in Canada report having an Aboriginal identity (61% First Nations, 32% Métis, 4.2% Inuit, 1.9% other Aboriginal identity, 0.8% more than one Aboriginal identity)

- 360,000 couples in Canada are mixed unions,* accounting for 4.6% of all married and common-law couples

- 65,000 same-sex couples were counted in the 2011 Census, 9.4% of whom are raising children

- 68,000 people in Canada are in the CAF Regular Forces, half of whom have children under 18

As His Excellency The Right Honourable David Johnston, Governor General of Canada, expressed at the Families in Canada Conference 2015, “Families, no matter their background or their makeup, bring new and special patterns to our diverse Canadian tapestry.” Join us as we recognize and celebrate family diversity, from coast to coast to coast.

Download the Family Diversity in Canada 2016 infographic.

* Statistics Canada defines a mixed union as “a couple in which one spouse or partner belongs to a visible minority group and the other does not, as well as a couple in which the two spouses or partners belong to different visible minority groups.”

Language, Labels and “Lone Parents”

Victoria Bailey

Lone parent, single parent, one-parent family, independent parent, non-married parent, alone parent, autonomous parent: the words or terms used to identify, or self-identify, adults who parent independently are diverse and subjective, and they have evolved over the years. While our choice of labels may seem trivial, language is powerful and loaded – it shapes how we see the world and the people in it. These familial terms, and the respective ideas they aim to convey, are at best blurry. What can seem like a valid category to one person may be considered a stereotype by another, and these labels can carry stigma with them that has an impact on family well-being and identity – particularly for single mothers,1 who account for 8 in 10 single parents in Canada.

Many labels are used to categorize “lone parents”

Statistics Canada uses the term lone parent to identify “Mothers or fathers, with no married spouse or common-law partner present, living in a dwelling with one or more children.” They are not alone in this choice of terminology: the UK’s Office for National Statistics also utilizes the term lone parent/lone parent family, as does the UK government’s statistics website. The Australia Bureau of Statistics, meanwhile, uses the term one-parent family and Statistics New Zealand lists the term sole parent in its definitions of census family classifications but tends to defer to the same terminology as Australia in census information-related texts.

The United States Census Bureau uses a number of different terms in their definitions and reports; phrases including female householder, no husband present, single parent and lone parent are used to describe different family and/or household structures. In Engendering Motherhood, sociologist Martha McMahon frequently uses the term “unwed mother”; however, this text is now 20 years old and, once a commonly used term, “unwed mother” is now infrequently applied in either dialogue or in media content. To many people, the phrase may now seem dated, archaic and even tied to (and measured more by) religious doctrine.

In a sense, none of the terms commonly used to identify single mothers are satisfactory in their ability to capture family experiences, because they use deficit language. Lone mothers and sole mothers could suggest to some that these parents are “on their own,” without supports, while many of these parents may have rich networks of support that include family, friends, community organizations and even former partners. One-parent families suggests a similar isolation, whereas the child(ren) in these families may have two parents, even if the parents have ended their relationship. Whereas single parent/s, as with “unwed mother,” suggests a deviation from a married-parent norm, it is rare for a determining label of “married parent/s” to be used in conversation or in text unless focusing specifically on the topics of parenting and marriage.

Overall, the use of a variety of terms does seem like a more sensitive, considerate and inclusive approach that is more appreciative of complex family forms and provides options for identifying families. Whether intended or not, what the differing US Census Bureau terms and more modern, emerging phrases such as autonomous parent and independent parent do signify is that terminology related to being a single parent seems to be evolving and progressing in a way that attributes power to the parent’s choice of familial circumstance.

Terms have changed over time, as have family experiences and realities

The use of single-parent synonyms and their attributed meanings have developed over time, reflecting ever-changing family realities. According to Statistics Canada, the proportion of lone parents in our nation is not drastically different from what it was 100 years ago, and it was nearly as high in 1931 (11.9%) as it was in 1981 (12.7%). But what does differ, is the reason behind those numbers, that is, a modern-day choice of relationship status versus a latter-day result of circumstance, often related to mortality rates. As highlighted in the Statistics Canada report Enduring Diversity: Living Arrangements of Children in Canada over 100 Years of the Census:

… diverse family living arrangements were in many cases a result of the death of one or more family members. Death within the family – of siblings, of mothers during or following complications from childbirth, of fathers serving in war, for example – was a much more common experience for young children in the early 20th century than today. In 1921, about 1 in 11 (8.9%) children aged 15 and under had experienced the death of at least one parent, while 4.1% had experienced the death of both parents.

The researchers go on to point out, “In comparison, in 2011, less than 1% of children aged 0 to 14 lived in a lone-parent family in which the parent was widowed.”

Throughout Canada’s history, there have been diverse paths to parenting independently, such as through adoption, sperm/egg donation, surrogacy, in vitro fertilization (IVF) or through separation, divorce from, or death of, a partner – or there never having been a partner in terms of a relationship to begin with. To avoid reinforcing stereotypes, it is important in any discussion about single parents to acknowledge this diversity and avoid generalization or homogenization.

Family labels can have an impact on identities

The language and terms we use to identify family forms matter, as they can carry negative connotations and meaning. An example of this can be found in the 2011 Census definition of family, in which Statistics Canada included stepfamilies for the first time:

A couple family with children may be further classified as either an intact family in which all children are the biological and/or adopted children of both married spouses or of both common-law partners or a stepfamily with at least one biological or adopted child of only one married spouse or common-law partner and whose birth or adoption preceded the current relationship.

While counting stepfamilies is a positive step toward capturing diverse family forms, the decision to contrast this with the label “intact family” could suggest, to some, that families deviating from this status are not intact, that is, not whole or complete due to lack of a partner living under the same roof as a parent and their child.

Labels such as single mother or single parent may also not be terms some people feel comfortable with. For example, in an online article entitled “Single Mother Was Not a Title I Wanted to Own. A Year Later It Still Isn’t,” blogger Mavis King writes how both she, and other mothers, do not want to be labelled as “single mothers”:

The problem with being a “single mum”… is the negative connotations it can conjure. At their worst single mums are associated with welfare, dole-bludging, unkempt and unruly kids. The single mother is just keeping it together, just scraping by. She’s not a heroine, no she’s responsible for her plight. She should have known better, should have never married him, shouldn’t have had children. And what about the kids? She’s selfish, the kids won’t do well at school, they’re worse off than their friends.

However, some parents proudly take ownership of wording that communicates their self-sufficiency. On the Wealthy Single Mommy blog, for example, Emma Johnson writes, “I feel totally fine calling myself a single mom: I float my family financially and am the primary caretaker of my kids.”

Stigma related to “lone motherhood” can affect family well-being

Negative stereotypes about single mothers such as those described by King, that is, assumptions that single mothers are struggling and irresponsible, or that their children are worse off than others, are often fuelled and reinforced in the media. A recent post-graduate study I completed focused on the representation of single mothers in Canadian news media found that coverage typically followed three main trends: a negatively biased dichotomy of representation, homogenization of single mothers and application of the term “single mother” being connected to gender-related identification of familial status rather than relevance to article information.

These depictions bolster stereotypes that can have measurable consequences. For example, in a 2011 study into rental discrimination, single mothers were found to be more than 14% less likely to be granted a positive reply to rental inquiries than a (heterosexual) couple. Similarly, women who participated in a qualitative focus group for my dissertation research reported that the stigma of being labelled a single mother had acted as a barrier that prevented them from leaving negative situations, including statements such as, “I was more scared of being a single mom than of staying in an abusive relationship.”

Family labels gloss over diverse experiences

While many texts claim that being raised in a home by single parents may predispose children to negative outcomes, some research challenges the causal relationship between growing up in a single-parent family and detrimental outcomes. As researchers Don Kerr and Roderic Beaujot point out, “Studies that do not take into account the pre-existing difficulties of children and their families have a tendency to overstate the effect of growing up in a single-parent family.” There are many circumstances in which mothers have created healthier environments for themselves and their children precisely because they ended a negative relationship to become single mothers.

Often, it seems that resources, such as money, time and community supports (i.e. extended family, friends and other community members) have a more significant impact on child and parent experience and/or outcome than a parent’s relationship status. As Jon Bernardes states in Family Studies: An Introduction, “Whilst Queen Victoria was a single parent for many years, she is not thought of as a ‘problem parent.’”

However, what is perhaps most important to note is that children tend not to care about how the census categorizes their parents, nor do they tend to repeatedly quantify any kind of relationship status distinction when speaking about their parents. While they may initially share their familial status with friends – for example, “It’s just me and my dad” or “My dad doesn’t live with us” – there’s most likely an informal, colloquial tone to this statement. It’s highly unlikely that, once this personal information is shared, any future descriptions of an event or issue linked to their parent/s includes determining terminology such as “my single father” or “my lone parent mother.” They most likely simply say “my mom” or “my dad” or “my whomever” with a sense of confident, unconditional, personal belonging and attachment marking the initial, and perhaps most crucial, signifier in that type of statement: “my.”

1 This article frequently uses the terms “single mothers” and “single parents” for consistency, but as it discusses, there are many recognized and preferred terms in use.

Victoria Bailey is a freelance writer and a student of women’s studies. She lives and works in Calgary, Alberta.

Work–Family Conflict Among Single Parents in the Canadian Armed Forces

Alla Skomorovsky, PhD

The demands of military life can be particularly stressful for military families due to deployments, relocations, foreign residency, periodic family separations, risk of injury or death of the military member, and long and unpredictable duty hours.

Although military families can usually manage demands individually, research has shown that competing and intersecting demands leave some feeling overwhelmed. This can be particularly true for single parents in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), who often manage these multiple roles with fewer resources. This could help explain why enlisted single parents (men and women) have been shown in previous research to be less satisfied with military life than their married counterparts.

Work–family conflict occurs when demands in the work domain are incompatible with demands in the family domain. Despite growing evidence that work–family conflict could be a considerable problem in Canada’s military families, the number of studies examining this topic is relatively small. In a recent qualitative study, the majority of single CAF parents reported that they were able to balance work and family life, but they admitted it was a challenge, primarily because many single parents are often the sole caregivers and financial providers for their families. As one study participant put it,

“So far, the balance between my professional life and my personal life has been quite good. But it’s difficult of course when it’s just me – having to stay late, for example, and still having to work on my phone. I have to have a BlackBerry because I can’t stay late – not as late as I used to anyway. But pretty good, overall.”

Little research exists about work–family conflict in Canada’s military families

Single CAF parents may face multiple deployments and must deal with being separated from their children and not being able to care for them. Caregiver arrangements may be more complicated in these families, as, for example, the children may have to relocate to another city to live with grandparents when their mother or father leaves for a mission. In addition, single parents who experience frequent relocations may find it challenging to establish or re-establish local social networks, which are often a valuable source of support.

A few studies have suggested that single-parent military families have unique military life-related challenges and substantial work–family conflict, but there isn’t much research about this topic in a Canadian context. Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (DGMPRA) conducted a study to address this gap and explore the main concerns of single CAF parents. An electronic survey was distributed to a random sample of Regular Force CAF members who had children 19 years of age or younger and were single, divorced, separated or widowed. In total, the results were available for 552 single parents.

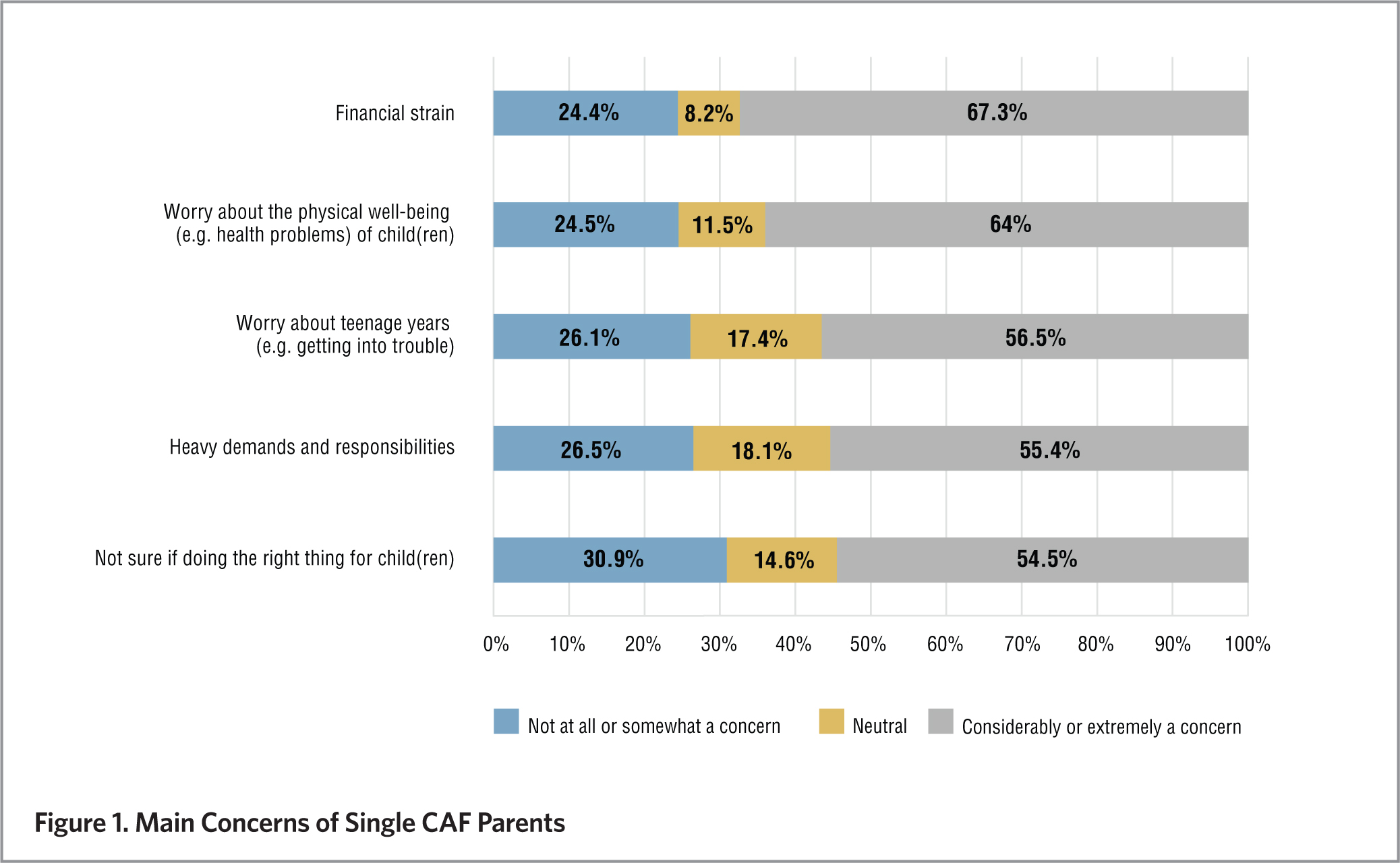

Single parents identified financial strain as a top concern; this is consistent with previous research showing that economic hardship is a leading cause of stress for single parents, both military and civilian. The second challenge for single parents was the worry about their child’s health and well-being. Although it has not been previously identified in research of civilian single parents, it is possible that this type of strain was high due to frequent parental absences related to deployment, training, unpredictable/inconsistent hours of work or overtime, common aspects of a military lifestyle. More than 60% of respondents identified financial strain and worry about health and well-being to be of considerable or extreme concern for them (see Figure 1). A large number of these parents (over 50%) were also concerned about dealing with adolescent years, doing the right thing for their children and their heavy demands and responsibilities.

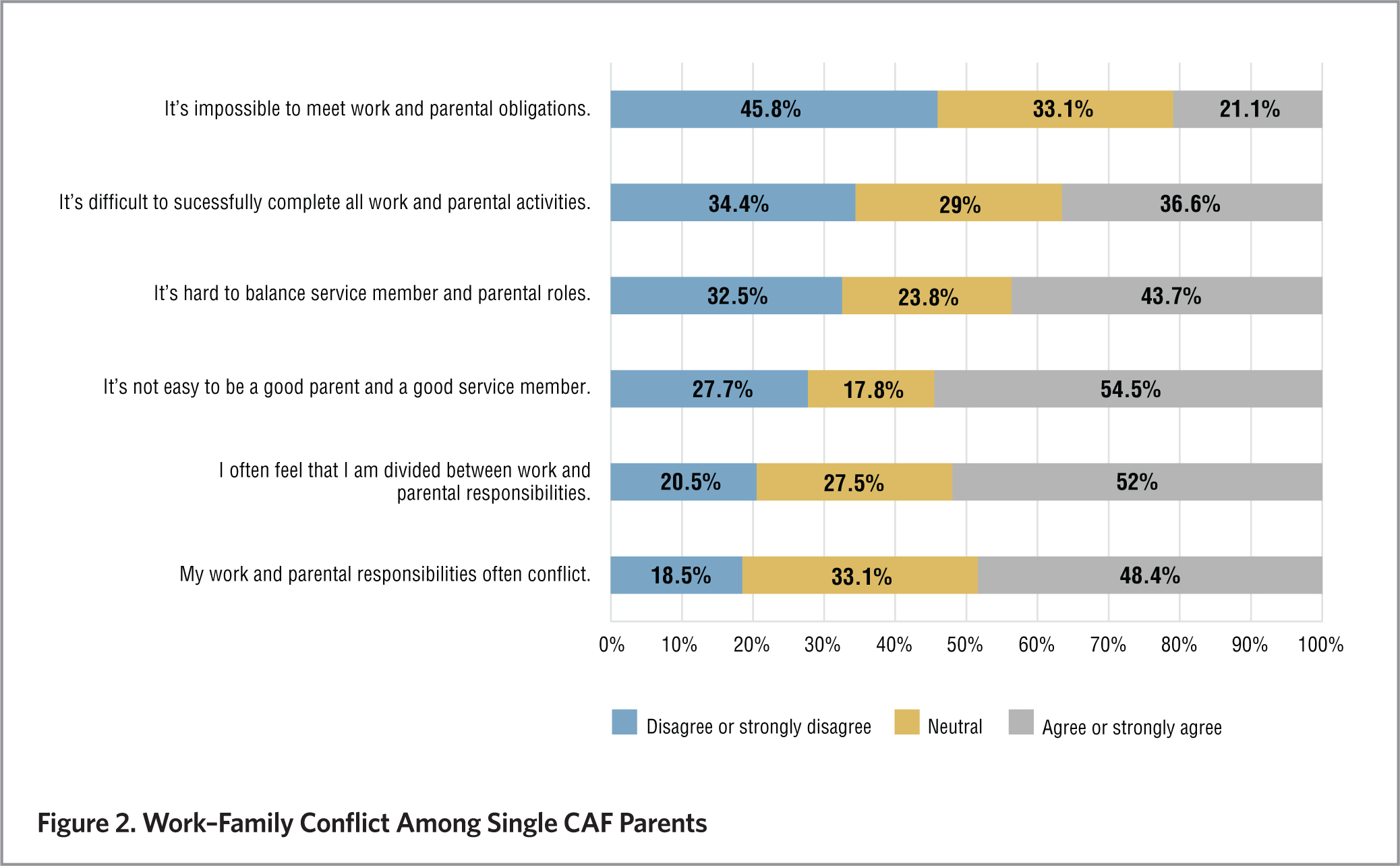

Managing parental and work responsibilities is not impossible, but it is hard

Single parents were asked to rate the extent to which their responsibilities as a service member and as a parent are in conflict. Most do not find it impossible to meet both parental and work responsibilities (see Figure 2). However, about 55% of respondents believe that it is not easy to be both a good parent and service member and feel divided between work and family responsibilities. About 44% of these parents believe it is hard to balance military and parental roles. This is consistent with previous research showing that single military parents are susceptible to experiencing work and family conflict.

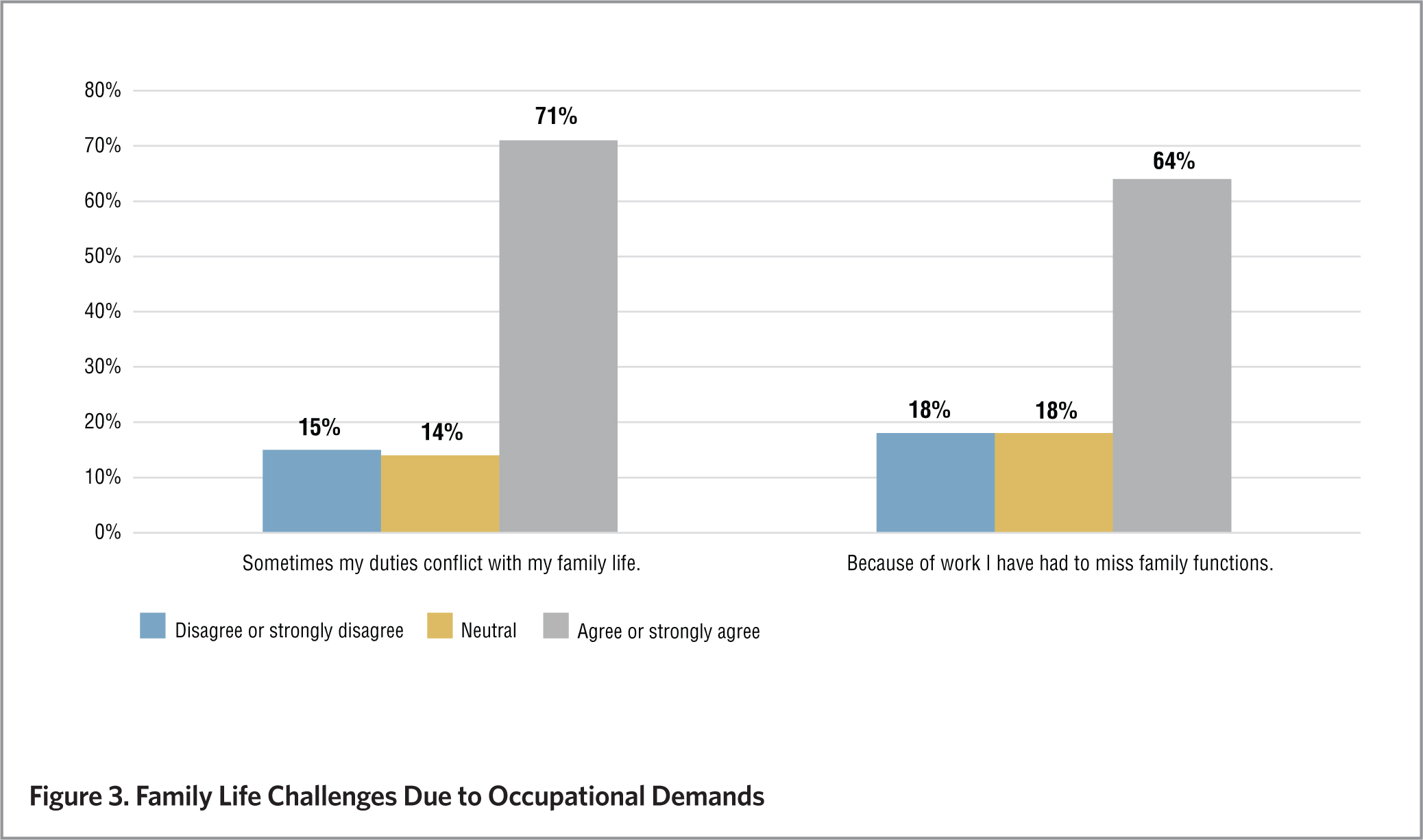

Further, participants were asked two questions about family life challenges due to occupational demands. When asked about the influence of work on family life, the vast majority of single military parents reported that work interferes with family life to at least some extent (see Figure 3). Approximately 70% of respondents noted that occupational demands sometimes conflicted with their family life, and 64% disclosed that they had missed family events due to occupational requirements.

In order to examine organizational support available to single parents in greater detail, single parents were asked whether they were aware of CAF programs and policies that could assist them in managing family and work demands. The results demonstrate that many single CAF parents are not aware of services available to them. For example, less than 10% of the participants mentioned that they were aware of Military Family Resource Centre services available to single military parents. This feeling was shared by a participant in the previously-mentioned qualitative study:

“Not everything is well advertised; you need to go and ask. If you are moving to the larger city, look for housing close to a [Military Family Resource Centre].”

Single CAF parents would benefit from work–family supports and greater awareness

Many single CAF parents are thriving, but the work–family conflict remains a considerable concern for some. A qualitative study participant expressed:

“I’m mainly concerned that being in the Canadian Forces may throw something unexpected at me, where I will be left in a position to choose between my career or my children.”

Single CAF parents could benefit from an increased awareness of, and access to, family assistance programs (e.g., Family Care Plans) and other programs, including counselling services. Furthermore, increasing awareness among managers and leaders about the work–family conflict challenges of single CAF parents could foster a more flexible and accommodating work environment. Finally, the ability of these parents to manage work and family responsibilities could be enhanced by tailoring programs and services to single parents (e.g., support groups) in order to increase emotional and instrumental support.

Although this research examines the main challenges and work–family conflict among single-parent CAF families, this is only a first step toward a full understanding of their well-being and unique needs. To further address the current gaps in knowledge, DGMPRA has developed a comprehensive research program related to military families, collaborating extensively with academia (e.g., via Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research). This body of research seeks to enhance the lives of Canadian military personnel, Veterans and their families. Supporting families is codified in the Canadian Forces Family Covenant, which acknowledges the immutable relationship between the state of military families and the CAF operational capacity.

We recognize the important role families play in enabling the operational effectiveness of the Canadian Forces and we acknowledge the unique nature of military life. We honour the inherent resilience of families and we pay tribute to the sacrifices of families made in support of Canada…

Canadian Forces Family Covenant

Consistent with the Family Covenant, it is important to continue developing the expert knowledge necessary to care for these families and to find ways to best meet their unique needs and ensure their individual and family well-being.

Dr. Alla Skomorovsky is a research psychologist at Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (DGMPRA), where she is a leader of the Military Families Research team. She conducts quantitative and qualitative research in the areas of resilience, stress, coping, personality and well-being of military families.

Dr. Skomorovsky received the inaugural Colonel Russell Mann Award for her research on work–family conflict and well-being among CAF parents at Forum 2015 – an event hosted by the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research.

This article can be downloaded in PDF format by clicking here.

Suggested Reading

T. Allen, D. Herst, E. Bruck and M. Sutton, “Consequences Associated with Work-to-Family Conflict: A Review and Agenda for Future Research,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308 (2000).

G.L. Bowen, D.K. Orthner and L. Zimmerman, “Family Adaptation of Single Parents in the United States Army: An Empirical Analysis of Work Stressors and Adaptive Resources,” Family Relations, 42, 293–304 (1993).

A.L. Day and T. Chamberlain, “Committing to Your Work, Spouse, and Children: Implications for Work–Family Conflict,” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 116–130 (2006).

A. Skomorovsky and A. Bullock, The Impact of Military Life on Single-Parent Military Families: Well-Being and Resilience (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Technical Report DRDC-RDDC-2015-R099), Ottawa, ON: Defence Research and Development Canada (2015).

Timeline: 50 Years of Families in Canada

Today’s society and today’s families would have been difficult to imagine, let alone understand, a half-century ago.

Families and family life have become increasingly diverse and complex, but families have always been the cornerstone of our society, the engine of our economy and at the centre of our hearts.

Learn about how families and family experiences in Canada have changed over the past 50 years with our new timeline!

Lone Mothers and Their Families in Canada: Diverse, Resilient and Strong

Mother’s Day is just around the corner, a time when children of all ages recognize and honour mothers, grandmothers and, increasingly, great-grandmothers! As we focus our attention on moms, many people worry about the prevalence of lone mothers and express concern about the well-being of their families.

“For many people, the term ‘lone mother’ brings to mind an image of a poor, struggling victim of sorts. They’re often seen as a single, growing group in crisis, toiling to raise children all on their own,” says Vanier Institute of the Family CEO Nora Spinks. “But this stereotype overlooks the diverse family experiences of lone mothers. This diversity, and the complexity of family life, is often lost in the statistics.”

“Of Canada’s 9.4 million families, only 16% lived in lone-parent families in 2011, with eight in 10 being led by women,” says Spinks. Many people feel that lone-parent families have been growing consistently over time. The truth, however, is more complex.

This belief is in part the result of looking only at trends since the 1960s, when the “traditional” family model with two married parents was at its peak. However, family structures fluctuate over time. Looking back further, lone-parent families were relatively common; the share of children living with a lone parent was 12% in 1931, similar to the 1981 rate of 13%.

While these numbers are close, the stories behind them differ because families faced different realities in these times. Many lone-parent families in the first half of the 20th century were in fact the result of mothers who died giving birth. The rate of children living in lone-parent families resulting from family death was eight in 10 in 1931. By the end of the century, it was only one in 10.

After the baby boom, a growing share of lone mothers were the result of separation and divorce, particularly following divorce law reform in 1968. This was just one of many changes for women in Canada during this period: women also gained greater capacity for family planning after the birth control pill emerged, and a growing number were pursuing higher education and joining the paid labour force, resulting in rising incomes.

This growth continues today, as the economic well-being of women improves. The incomes of lone mothers grew by 51% between 1998 and 2008 (compared to 13% among men). The income gap among lone parent families has shrunk: lone-parent families headed by women had incomes worth 53% of those headed by men in 1998, but 70% by 2008.

The prevalence of lone mothers, and lone-parent families in general, has always fluctuated over time. The reasons change, but the reality of ongoing change is constant. Families adapt and react to change, regardless of their form or the number of parents within.

The “lone mother” label often leads to another misperception: that these moms are without support. “Lone” suggests that these mothers are raising a family without any outside support (as does “sole” in the alternate label of “sole support mother”).

Often, these moms are not raising their children alone. Sometimes support comes from ex-partners. In 2011, 35% of separated or divorced parents said that decisions about their child(ren)’s health, religion/spirituality or education were made jointly or alternately. That same year, 9% said that their child(ren) live equally between their homes.

Support can come from other family members as well. In 2011, 8% of grandparents lived with their grandchildren, and one-third of these technically lived in “lone” parent households. “That’s 600,000 grandmas and grandpas in the family home, many of whom provide care and support to both generations,” says Spinks.

Multigenerational living is on the rise. It’s relatively common among immigrant and Aboriginal families. Shared living makes it easier to share costs, pool savings and provide care. Three-quarters of grandparents in lone-parent homes report some responsibility for household costs.

Many lone mothers may be in committed relationships with a partner who contributes to their family life, but choose to live in “living apart together” (LAT) couples. According to Statistics Canada, 8% of women aged 20 and over (1.9 million) are in LAT couples. However, we do not know how many of these are lone mothers.

Just as families are diverse, so are the forms of support they can provide and receive. Not all networks of care or forms of support are easy to capture with statistics. Lone mothers can be supported by friends or family members who offer help in ways such as child care; financial loans; living space; transportation; used toys, books or other goods; meals or groceries; and emotional support.

“Any portrait or discussion of modern lone mothers requires an open mind. One needs to understand that family life is diverse and complex, and families of all kinds are adaptable, strong and resilient. Myths and stereotypes about particular family types only lead to misunderstandings,” says Spinks. “That idea has guided the Vanier Institute of the Family since its founding 50 years ago, and will continue to as we study Canada’s families in the years ahead.”