A brief overview of statistics related to Black families in Canada

Topic: Demographics

Nicole Denier

Nicole Denier is a sociologist with expertise in work, labour markets, and inequality. She has led award-winning work on the intersection of family diversity and economic inequality, including research on the economic wellbeing of 2SLGBTQI+ people in Canada and immigrants in North America. Nicole is currently an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Alberta. She serves as Co-Director of the Work and Family Researchers Network Early Career Fellows program, as well as on the editorial boards of Canadian Studies in Population and the Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie.

Simona Bignami

Simona Bignami is a demographer specializing in quantitative methods and family dynamics. Broadly speaking, she is interested in the relationship between social influence, family dynamics, and demographic outcomes and behaviours, and the extent to which empirical evidence helps us understand this relationship. Her most recent work focuses on migrants’ and ethnic minorities’ family dynamics, attempting to improve their measurement with innovative data and methods, and to understand their role for demographic and health outcomes. Her research on these topics takes a comparative perspective, and spans from developing to developed country settings. Although her research is quantitative, she has experience collecting household survey data and conducting qualitative interviews and focus groups in different settings.

Maude Pugliese

Maude Pugliese is an Associate Professor at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (Université du Québec) in the Population Studies program and holds the Canada Research Chair in Family Financial Experiences and Wealth Inequality. She is also the scientific director of the Partenariat de recherche Familles en mouvance, which brings together dozens of researchers and practitioners to study the transformations of families and their repercussions in Quebec. In addition, she is the director of Observatoire des réalités familiales du Québec/Famili@, a knowledge mobilization organization that diffuses the most recent research on family issues in Quebec to a broad public in accessible terms. Her current research work focuses on the intergenerational transmission of wealth and of money management practices, gender inequalities in wealth and indebtedness, and how new intimate regimes (separation, repartnering, living apart together, polyamory, etc.) are transforming ideals and practices of wealth accumulation.

Andrea Doucet

Andrea Doucet is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Gender, Work, and Care, Professor in Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University, and Adjunct Professor at Carleton University and the University of Victoria (Canada). She has published widely on care/work policies, parental leave policies, fathering and care, and gender divisions and relations of paid and unpaid work. She is the author of two editions of the award-winning book Do Men Mother? (University of Toronto Press, 2006, 2018), co-author of two editions of Gender Relations: Intersectionality and Social Change (Oxford, 2008, 2017), and co-editor of Thinking Ecologically, Thinking Responsibly: The Legacies of Lorraine Code (SUNY, 2021). She is currently writing about social-ecological care and connections between parental leaves, care leaves, and Universal Basic Services. Her recent research collaborations include projects with Canadian community organizations on young Black motherhood (with Sadie Goddard-Durant); feminist, ecological, and Indigenous approaches to care ethics and care work (with Eva Jewell and Vanessa Watts); and social inclusion/exclusion in parental leave policies (with Sophie Mathieu and Lindsey McKay). She is the Project Director and Principal Investigator of the Canadian SSHRC Partnership program, Reimagining Care/Work Policies, and Co-Coordinator of the International Network of Leave Policies and Research.

Donna S. Lero

Donna S. Lero is University Professor Emerita and the inaugural Jarislowsky Chair in Families and Work at the University of Guelph, where she co-founded the Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being. Donna does research in Social Policy, Work and Family, and Caregiving. Her current projects focus on maternal employment and child care arrangements, parental leave policy, and disability and employment, as well as the Inclusive Early Childhood Service System (IECSS) project and the SSHRC project Reimagining Care/Work Policies.

Liv Mendelsohn

Liv Mendelsohn, MA, MEd, is the Executive Director of the Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence, where she leads innovation, research, policy, and program initiatives to support Canada’s caregivers and care providers. A visionary leader with more than 15 years of experience in the non-profit sector, Liv has a been a lifelong caregiver and has lived experience of disability. Her experiences as a member of the “sandwich generation” fuel her passion to build a caregiver movement in Canada to change the way that caregiving is seen, valued, and supported.

Over the course of her career, Liv has founded and helmed several organizations in the disability and caregiving space, including the Wagner Green Centre for Accessibility and Inclusion and the ReelAbilities Toronto Film Festival. Liv serves as the chair of the City of Toronto Accessibility Advisory Committee. She has received the City of Toronto Equity Award, and has been recognized by University College, University of Toronto, Empowered Kids Ontario, and the Jewish Community Centres of North America for her leadership. Liv is a senior fellow at Massey College and a graduate of the Mandel Institute for Non-Profit Leadership and the Civic Action Leadership Foundation DiverseCity Fellows program.

About the Organization: The Canadian Centre for Caregiving Excellence supports and empowers caregivers and care providers, advances the knowledge and capacity of the caregiving field, and advocates for effective and visionary social policy, with a disability-informed approach. Our expertise and insight, drawn from the lived experiences of caregivers and care providers, help us campaign for better systems and lasting change. We are more than just a funder; we work closely with our partners and grantees towards shared goals.

Susan Prentice

Susan Prentice holds the Duff Roblin Professor of Government at the University of Manitoba, where she is a professor of Sociology. She specializes in family policy broadly, and child care policy specifically. She has written widely on family and child care policy, and a list of her recent publications can be found at her UM page. At the undergraduate and graduate level, she teaches family policy courses. Susan works closely with provincial and national child care advocacy groups, and is a member of the Steering Committee of the Childcare Coalition of Manitoba.

Yue Qian

Yue Qian (pronounced Yew-ay Chian) is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. She received her PhD in Sociology from Ohio State University. Her research examines gender, family and work, and inequality in global contexts, with a particular focus on North America and East Asia.

Shelley Clark

Shelley Clark, James McGill Professor of Sociology, is a demographer whose research focuses on gender, health, family dynamics, and life course transitions. After receiving her PhD from Princeton University in 1999, Shelley served as program associate at the Population Council in New York (1999–2002) and as an Assistant Professor at the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago (2002–2006). In the summer of 2006, she joined the Department of Sociology at McGill, where in 2012 she became the founding Director of the Centre on Population Dynamics. Much of her research over two decades has examined how adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa make key transitions to adulthood amid an ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Additional work has highlighted the social, economic, and health vulnerabilities of single mothers and their children in sub-Saharan Africa. Recently she has embarked on a new research agenda to assess rural and urban inequalities and family dynamics in the United States and Canada. Her findings highlight the diversity of family structures in rural areas and the implications of limited access to contraception on rural women’s fertility and reproductive health.

Isabel Côté

Isabel Côté is a full professor in the department of social work at Université du Québec en Outaouais. She holds the Canada Research Chair on Third-Party Reproduction and Family Ties, is a member of Partenariat Famille en mouvance (a research partnership on the changing family) and of the Réseau québécois en études féministes (RéQEF) (a Quebec network for feminist studies). Her research program aims to develop a global understanding of third-party reproduction that brings together the viewpoints of all parties, including parents, donors, surrogates, the children conceived this way, and the extended families. Using innovative qualitative methodologies, her work draws on the theoretical contributions of sociology of the family, kinship anthropology, and feminist and LGBTQ studies, and takes a fresh look at contemporary family realities. In an innovative way, her work considers children as full agents in the construction of knowledge about families created thanks to third-party reproduction. Lastly, the results of her work provide material, based on empirical data, to inform the social debate about the issues raised by third-party reproduction while also suggesting courses of action to better support the wellbeing of the people concerned.

Issue Brief: Family Change and Diversity in Canada

An overview of family diversity and change across Canada

UN Report: Interlinkages Between Demographic Change, Migration, and Urbanization in Canada: Policy Implications

An overview of policy implications on demographic change, migration, and urbanization in Canada

Fertility Rate in Canada Fell to (Another) Record Low in 2022

New data shows Canada’s fertility rate is at (another) new record low.

Metrics to Meaning: Gender Diversity and Families in Canada

An overview of Census changes that strengthen our portrait of diversity

Migration and Urbanization Trends and Family Wellbeing in Canada: A Focus on Disability and Indigenous Issues

A report prepared for Expert Group Meeting on megatrends and families

Infographic: Who Are Employed Caregivers in Canada?

Research on Aging, Policies and Practice has published new data on working caregivers.

Canada’s “Family Portrait”: Measuring Families in the Census

Nora Galbraith from Statistics Canada discusses the upcoming Census 2021 release on families in Canada.

In Conversation: Rachel Margolis on Divorce in Canada

Rachel Margolis shares her thoughts on new data on divorce in Canada.

Census 2021: Generations and Population Aging in Canada

2021 Census releases from Statistics Canada provide a generational lens on population aging.

In Conversation: Nora Galbraith on Divorce Trends in Canada

Nora Galbraith from Statistics Canada discusses new data on divorce in Canada.

Divorce in Canada: A Tale of Two Trends

Nathan Battams shares new findings on divorce trends in Canada over the last 30 years.

Research Recap: Wellbeing of Middle-Aged and Older Adults Without Partners or Children

Dr. Rachel Margolis shares new research on the well-being of older adults without close kin.

Timeline: 50 Years of Families in Canada (1971‑2021)

Learn about how families and family experiences in Canada have changed over the past 50 years with our new timeline!

Metrics to Meaning: Capturing the Diversity of Couples in Canada

Kathya Aathavan measures the growing diversity of couple relationships in Canada.

Research Recap: Divorced and Unpartnered: New Insights on a Growing Population in Canada

Research recap by Rachel Margolis, PhD, and Youjin Choi, PhD

In Conversation: Rachel Margolis on Divorce Trends in Canada

Nathan Battams

Download In Conversation: Rachel Margolis on Divorce Trends in Canada

(February 10, 2020) Families in Canada have evolved considerably across generations, as have patterns of coupling (i.e. marriage, living common-law) and uncoupling (i.e. separation and divorce) that have an impact on families and family well-being. While a large and growing body of family research has documented how divorce can impact individuals and their families, our understanding of how this has changed over time has been significantly affected by a lack of publicly available vital statistics data in Canada over the past decade.

Rachel Margolis, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Western Ontario and panellist at the Families in Canada Conference 2019, joined Vanier Institute Communications Manager Nathan Battams to discuss Canada’s evolving data landscape in her recent study published in Demographic Research exploring recent divorce trends and the use of administrative data to fill the data gap on divorce.

Tell me about your recent study on divorce in Canada, and what made you interested in this topic…

This study, which was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), addresses an issue I’ve been thinking about for a long time. While doing my research and teaching demography over the years, I’ve often been frustrated by the fact that we haven’t had national measures on marriage and divorce in Canada since 2008, when vital statistics data stopped being analyzed and reported by Statistics Canada. My collaborators Youjin Choi, Feng Hou and Michael Haan all worked on this project with me to learn about recent changes in divorce.

The real motivation for this study was to strengthen our understanding of demographic changes in Canada.

This is important because marriage and divorce data provide important and unique measures for studying families and family life. It matters for understanding fertility trends, since formal unions are the context in which most babies are born. It matters for understanding family finances, since formal unions are vehicles for wealth accumulation, and they can tell us a lot about family resources and provisions, such as housing and caregiving. The real motivation for this study was to strengthen our understanding of demographic changes in Canada.

Historically, information on marriage and divorce in Canada has been collected and managed by a system called Vital Statistics. Vital statistics exist in most countries in some form as the means of collecting population data on things like marriage, divorce, births and deaths, although some countries have recently moved away from this mode of data collection and are exploring alternate strategies. In the United States, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) discontinued divorce and marriage statistics in 1996, as it was argued that similar data could be collected more easily and inexpensively through surveys, which are now used to gather information about marriage and divorce rates.

And while we haven’t had data published by Statistics Canada on marriage and divorce trends since 2008, there hasn’t been any alternative data source in place, like there is in the U.S. The decision to stop publishing these data was made for a variety of reasons, including fiscal constraints, some problems with data compatibility across provinces and territories, and a reported underutilization of these data online. But with no alternative data source, there has since been a decade-long data gap on marriage and divorce in Canada.

The first data gap this study sought to address was whether other types of data can fill this gap. Though some researchers have already used administrative data to look at the effects of changes in marital status on other outcomes, we haven‘t really assessed the quality of these divorce measures.1

Second, there has been no national data on how the divorce rate in Canada has changed since vital statistics data collection ceased in 2008. Since then, research on divorce in Canada has relied on information about the current marital or conjugal status of individuals, which doesn’t provide divorce rates. The latter are important to track because they tell us a lot about how things are changing over time. Current marital status is not an effective indicator of divorce because many people who divorce later repartner and/or remarry. Our study used anonymized administrative data from tax records to estimate the divorce rate – the first to do so.

A third gap is that we don’t have information on the changing age patterns of divorce in Canada since 2008. We do know that there are significant shifts taking place in comparable countries, such as the United States, and in Europe. In the U.S., we know that divorce rates among those aged 50 and older – often referred to as “grey divorce” – doubled in the 1990s and 2000s. There are a lot of reasons for this, but many of the same trends happening among baby boomers in the U.S. are likely happening to boomers in Canada as well. But, with no data, we don’t really know whether there’s also been a “grey divorce revolution” in Canada.

What did you find in your study on divorce in Canada?

First of all, we found that the divorce rate in Canada can indeed be measured somewhat well with administrative data, when comparing it with vital statistics data before 2008. When we extrapolate after 2008 with this approach, we see a decline in the annual divorce rate between 2009 and 2016. The annual divorce rate was about 10 divorces per 1,000 married women in the early 2000s and this declined starting in 2006, reaching 6 divorces per 1,000 married women in 2016.

Second, we found a shifting age distribution among people getting divorced. In the early 1990s, most divorces in Canada were granted to people in their 20s and 30s. Fifty-one percent of all divorces were granted to women aged 20–39, 42% went to those 40–59 and only 7% to those 60 and above. Over the last 20 years, it has become more common for divorces to occur later. For example, in 2016, only 28% of divorces were granted to women 20–39, 57% were to women 40–59 and 15% to those 60 and above. Divorce, then, has become increasingly common at older ages.

Fewer people are getting married and those that do get married are more likely to be from groups with lower divorce rates.

Third, there have been changes in divorce rates for both younger and older Canadians. Divorce rates among adults in their 20s and 30s fell by about 30% in the last decade. Research from other countries helps explain this, as fewer people are getting married and those that do get married are more likely to be from groups with lower divorce rates (highly educated with lots of resources), and they are therefore less likely to get divorced while in this age group, and those who do are in potentially higher quality marriages than they were in the past.2 Even though age-specific divorce rates are highest for younger women, they’ve been declining over the period of our analysis.

Meanwhile, divorce rates for older people in Canada have increased slightly through the 1990s and 2000s, but nothing as significant as the “grey divorce revolution” in the U.S., and this now seems to have ceased. In the U.S., divorce rates for those aged 50 and older doubled between 1990 and 2010, from 4.87 to 10.05 divorces per 1,000 married persons.3 We found that the comparable increase in Canada between 1991 and 2008 was from 4.02 to 5.17 divorces per 1,000 married persons during this period (+25%). Since 2008, we find no further increase in divorce rates for older adults in Canada.

Divorce rates for older people in Canada have increased slightly through the 1990s and 2000s, but nothing as significant as the “grey divorce revolution” in the U.S.

The fourth thing we explored was comparing divorce trends in Canada with what’s been seen in the U.S. We found that trends in divorce in Canada are similar to trends in the U.S. Divorce rates were relatively flat in the 1990s and early 2000s and then declined more recently (see Figure 1). However, one important difference is that divorce rates are about half in Canada of what they are in the U.S. For example, for most of the 1990s and early 2000s, divorce rates in the U.S. sat at about 20 divorces per 1,000 married women, and the Canadian rate was about 10 divorces per 1,000 married women. More recently, divorce rates in the U.S. were 16.7 divorces per 1,000 married women in 2016, and the comparable number for Canada is 6.22.

Overall, we found that using tax data provided invaluable insights into recent trends in divorce in Canada and helps inform whether administrative data can be used to fill the data gap on divorce. However, we also found important caveats regarding data quality in recent years, as coverage rates of divorced people in the tax data has declined to some degree (i.e. divorces have been undercounted in tax data relative to vital statistics). This is potentially problematic, because it could lead us to increasingly underestimate divorce in the tax data over time, and it could become unclear how much of a decline in divorce in recent years is due to a decline in data quality.

Looking ahead, as a family researcher, how would you complete the phrase “Wouldn’t it be great if…”

To address data gaps, there’s been a growing focus in Canada and other countries to use administrative data rather than survey data to learn about the population. There are many reasons for this and it’s not necessarily a bad thing, but we have to be careful about different issues that arise with data quality – and that’s what we found when we used tax data to look at divorce trends.

In wanting to address this, I would say, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could add questions about marriage and divorce in the last year to a large annual survey in Canada with a known high response rate?” A survey with a large enough sample size, such as Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey or the long-form census, could serve as an efficient and reliable vehicle for collecting these important data.

We can also learn from our neighbours to the south, who added questions about recent changes in marital status to the American Community Survey in 2008. This could provide answers to how marriage and divorce are changing and how the percentage of marriages that will end in divorce is changing over time – invaluable insights for researchers, policy makers, service providers and others with an interest in families in Canada.

Rachel Margolis, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Western Ontario and a Vanier Institute of the Family contributor.

Nathan Battams is Communications Manager at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Access the study in Demographic Research (open access):

Rachel Margolis, PhD, Youjin Choi, PhD, Feng Hou, PhD, and Michael Haan, PhD, “Capturing Trends in Canadian Divorce in an Era Without Vital Statistics,” Demographic Research 41, Article 52 (December 20, 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/39lHEBD.

More from Rachel Margolis:

- Rachel Margolis, Grandparent Health and Family Well-Being, The Vanier Institute of the Family. Link: https://bit.ly/2Ugvm9s.

- Rachel Margolis, Feng Hou, Michael Haan and Anders Holm, “Use of Parental Benefits by Family Income in Canada: Two Policy Changes,” Journal of Marriage and Family 81(2) (November 13, 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/2RTPSuN.

- Rachel Margolis and Laura Wright, “Healthy Grandparenthood: How Long Is It, and How Has It Changed?,” Demography 54 (October 10, 2017). Link: https://bit.ly/36W9ClM.

- Rachel Margolis, “The Changing Demography of Grandparenthood,” Journal of Marriage and Family 78(3) (March 14, 2016). Link: https://bit.ly/380Ow7c.

- Rachel Margolis and Natalie Iciaszczyk, “The Changing Health of Canadian Grandparents,” Canadian Studies in Population 42(3-4): 63-76. Link: https://bit.ly/36TLNv1.

Notes

- This study did not focus on separations. Relative to the number of divorced people, the number who are legally separated but not divorced is small, and most separations end in divorce. In addition, separation rates are not a traditional demographic measure.

- Phillip N. Cohen, “The Coming Divorce Decline,” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5 (August 28, 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/2RK7J7j.

- Susan L. Brown and Lin I-Fen, “The Gray Divorce Revolution: Rising Divorce Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults, 1990–2010,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 67(6) (2012). Link: https://bit.ly/2UdlDAB.

A Snapshot of Grandparents in Canada (May 2019 Update)

Canada’s grandparents are a diverse group. Many of them contribute greatly to family functioning and well-being in their roles as mentors, nurturers, caregivers, child care providers, historians, spiritual guides and “holders of the family narrative.”

As Canada’s population ages and life expectancy continues to rise, their presence in the lives of many families may also increase accordingly in the years to come. With the number of older Canadians in the workforce steadily increasing, they are playing a greater role in the paid labour market – a shift felt by families who rely on grandparents to help provide care to their grandchildren or other family members. All the while, the living arrangements of grandparents continue to evolve, with a growing number living with younger generations and contributing to family households.

Using newly released data from the 2017 General Social Survey, we’ve updated our popular resource A Snapshot of Grandparents in Canada, which provides a statistical portrait of grandparents, their family relationships and some of the social and economic trends at the heart of this evolution.

Highlights:

- In 2017, 47% of Canadians aged 45 and older were grandparents, down from 57% in 1995.1

- In 2017, the average age of grandparents was 68 (up from 65 in 1995), while the average age of first-time grandparents was 51 for women and 54 for men in 2017.2, 3

- In 2017, nearly 8% of grandparents were aged 85 and older, up from 3% in 1995.4

- In 2017, 5% of grandparents in Canada lived in the same household as their grandchildren, up slightly from 4% in 1995.5

- In 2017, grandparents who were born outside Canada were more than twice as likely as Canadian-born grandparents to live with grandchildren (9% and 4%, respectively), the result of a complex interplay of choice, culture and circumstance.6

Download A Snapshot of Grandparents in Canada (May 2019) from the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Battams, N. (2019). A snapshot of grandparents in Canada. The Vanier Institute of the Family. https://doi.org/10.61959/disx1332e

Published on May 28, 2019

1 Statistics Canada, “Family Matters: Grandparents in Canada,” The Daily (February 7, 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/2BnyyFO.

2 Ibid.

3 No comparator provided because this is the first time the question has been asked in the General Social Survey.

4 Ibid.

5 Statistics Canada, “Family Matters: Grandparents in Canada.”

6 Ibid.

2018 UPDATE: A Snapshot of Military and Veteran Families in Canada

Download A Snapshot of Military and Veteran Families in Canada

Canada’s military and Veteran families are diverse, resilient and strong, and they are a source of pride for the country. They engage with – and play important roles in – their workplaces, communities and society as a whole.

The “military journey” is often characterized by mobility, absence and the risk of illness, injury or death. Professionals and practitioners can benefit from “military literacy” – an understanding of the unique experiences and lifestyle characteristics of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel, Veterans and their families. To enhance understanding of these families and their experiences, the Vanier Institute of the Family is highlighting new research and data1 on military and Veteran families in Canada with a 2018 update of A Snapshot of Military and Veteran Families in Canada.

Military families experience high mobility and frequent periods of separation

- Every year in Canada, an estimated 10,000 military families are relocated due to postings (8,000 of whom move to new provinces), which accounts for one-quarter of all Regular Forces personnel in Canada.

- In 2018, among surveyed CAF Regular Force members, nearly three in 10 (29%) reported that they had relocated at least four times due to military postings throughout their career.

- In 2017, two-thirds of Regular Forces personnel reported experiencing extended absences from their family.

Military children are affected by relocations, but they are resilient and most adjust quickly

- Research shows that while most military children do find relocation stressful, they are resilient, and this stress typically diminishes within a half-year after moving.

- In 2016, among surveyed CAF parents, only one in 10 (10%) reported that their child(ren) “had trouble adjusting after moving/relocation,” while nearly half (47%) did not experience any issues.

The majority of Veterans and their families do not experience difficulties in transition to civilian life

- In 2016, Veterans were more likely to report that the transition to civilian life was easy compared with those who said it was difficult for themselves and their families.

- 52% said the transition was “easy” for themselves, 32% said it was “difficult.”

- 57% said the transition was “easy” for their partners, 28% said it was “difficult.”

- 60% said the transition was “easy” for their children, 17% said it was “difficult.”

- Nearly nine in 10 Veterans reported being satisfied/very satisfied with life (86%) and their family (88%).

Note

- Source information can be found in the document.

Battams, N. (2018). 2018 Update: A snapshot of military and veteran families in Canada. The Vanier Institute of the Family. https://doi.org/10.61959/cyth4819e

Facts and Stats: Divorce, Separation and Uncoupling in Canada

Just as families continuously evolve, so do the interpersonal relationships at the heart of family life. Every year, thousands of Canadians come together to form committed family relationships – some of whom decide to raise children together – and sometimes, a variety of reasons may compel them to end their relationship, which can result in diverse, unique and often difficult transitional experiences for the family.

Patterns of coupling or partnering and uncoupling or unpartnering have evolved throughout Canada’s history in response to social, economic, cultural and legal changes. While divorce rates were low for most of the 20th century due to restrictive social norms and legal processes, there has since been an increase in the share of families who have experienced separation, divorce and uncoupling – particularly following the liberalization of divorce through the 1968 Divorce Act and further amendments in 1986.

Whether it’s separation and divorce following a marriage, or the uncoupling of a common-law union, this change can be emotionally, socially, legally and/or financially challenging for family members. Current research shows, however, that the impact on adults and children – including the speed and degree of adjustment – varies widely and is shaped by post-divorce circumstances, access to community programs and services, as well as the availability of information, resources and support during the transition.

In May 2018, the federal government proposed amendments to the Divorce Act to mitigate the adversarial nature of family court proceedings following separation and divorce. These changes are meant to serve the “best interests of the children,” and include defining what these “best interests” are, updating adversarial language such as “custody” and “access” to terms that include “parenting orders” and “parenting time,” establishing clear guidelines for when one parent wants to relocate with a child, making it easier for people to collect support payments, strengthening the capacity of courts to address family violence and compelling lawyers to encourage clients to use family-dispute resolution services, such as mediation.

In this evolving social, cultural and legal context, our new fact sheet uses data from the General Social Survey1 to explore family experiences of divorce, separation and uncoupling in Canada.

Highlights include:

- In 2017, an estimated 9% of Canadians aged 15 and older were divorced or separated (and not living common law), up from 8% in 1997.

- In 2016, surveyed Canadian lawyers reported charging an average $1,770 in total fees for uncontested divorce cases and $15,300 for contested divorce cases.

- In 2011, nearly 1 in 5 Canadians (19%) said that their parents are divorced or separated, nearly twice the share in 2001 (10%).

- In 2011, two-thirds (66%) of divorced Canadians said they do not have remarriage intentions (23% said they were uncertain).

Download Facts and Stats: Divorce, Separation and Uncoupling in Canada (PDF)

Among top reasons for divorces in Canada we can find:

- Infidelity: Extramarital affairs break trust and create an irreparable rift between partners.

- Communication Breakdown: Lack of effective communication leads to misunderstandings and resentment, causing many marriages to fail.

- Addictions and Gambling problem: Addiction to legal online casinos can lead to financial ruin and neglect of family responsibilities, causing significant marital issues and divorce.

- Financial Problems: Disagreements over spending, debt, and financial priorities often strain marriages.

Notes

- The most recent data available on this topic is from 2011. This fact sheet will be updated when new data is released in Fall 2018.

Families in Canada Interactive Timeline

Today’s society and today’s families would have been difficult to imagine, let alone understand, a half-century ago. Data shows that families and family life in Canada have become increasingly diverse and complex across generations – a reality highlighted when one looks at broader trends over time.

But even as families evolve, their impact over the years has remained constant. This is due to the many functions and roles they perform for individuals and communities alike – families are, have been and will continue to be the cornerstone of our society, the engine of our economy and at the centre of our hearts.

Learn about the evolution of families in Canada over the past half-century with our Families in Canada Interactive Timeline – a online resource from the Vanier Institute that highlights trends on diverse topics such as motherhood and fatherhood, family relationships, living arrangements, children and seniors, work–life, health and well-being, family care and much more.

View the Families in Canada Interactive Timeline.*

Full topic list:

- Motherhood

o Maternal age

o Fertility

o Labour force participation

o Education

o Stay-at-home moms

- Fatherhood

o Family relationships

o Employment

o Care and unpaid work

o Work–life

- Demographics

o Life expectancy

o Seniors and elders

o Children and youth

o Immigrant families

- Families and Households

o Family structure

o Family finances

o Household size

o Housing

- Health and Well-Being

o Babies and birth

o Health

o Life expectancy

o Death and dying

View all source information for all statistics in Families in Canada Interactive Timeline.

* Note: The timeline is accessible only via desktop computer and does not work on smartphones.

Published February 8, 2018

A Snapshot of Family Diversity in Canada (February 2018)

Download A Snapshot of Family Diversity in Canada (February 2018).

For more than 50 years, the Vanier Institute of the Family has monitored, studied and discussed trends in families and family life in Canada. From the beginning, the evidence has consistently made one thing clear: there is no single story to tell, because families are as diverse as the people who comprise them.

This has always been the case, whether one examines family structures, family identities, family living arrangements, family lifestyles, family experiences or whether one looks at the individual traits of family members, such as their ethnocultural background, immigration status, sexual orientation or their diverse abilities.

Building on our recent infographic, Family Diversity in Canada (2016 Census Update), our new Statistical Snapshot publication provides an expanded and more detailed portrait of modern families in Canada, as well as some of the trends that have shaped our vibrant and evolving family landscape over the years. Based on current data and trend analysis, this overview shows that diversity is, was and will continue to be a key characteristic of family life for generations to come – a reality that contributes to Canada’s dynamic and evolving society.

Highlights include:

- According to Statistics Canada, there were 9.8 million Census families living across Canada in 2016.

- 66% of families in Canada include a married couple, 18% are living common-law and 16% are lone-parent families – diverse family structures that continuously evolve.

- Among Canada’s provinces, people in Quebec stand out with regard to couple/relationship formation, with a greater share living common-law than the rest of Canada (40% vs. 16%, respectively) and fewer married couples (60% vs. 84%, respectively) in 2016.

- In 2016, 1.7 million people in Canada reported having an Aboriginal identity: 58% First Nations, 35% Métis, 3.9% Inuk (Inuit), 1.4% other Aboriginal identity and 1.3% with more than one Aboriginal identity.

- In 2016, 22% of people in Canada reported that they were born outside the country – up from 16% in 1961.

- In 2016, more than 1 in 5 people in Canada (22%) reported belonging to a visible minority group, 3 in 10 of whom were born in Canada.

- 73,000 same-sex couples were counted in the 2016 Census, 12% of whom are raising children.

- In 2016, there were nearly 404,000 multi-generational households in Canada – the fastest-growing household type since 2001 (+38%).

- In 2011, 22% of Inuk (Inuit) grandparents, 14% of First Nations grandparents and 5% of Métis grandparents lived with their grandchildren, compared with 3.9% of among non-Indigenous grandparents.

- In 2014, 1 in 5 Canadians aged 25 to 64 reported living with at least one disability. Disability rates were higher for women (23%) than men (18%).

- More than one-quarter (27%) of Canadians surveyed in 2014 said religion is “very important” in their lives.

- One-quarter of Canadians reported “no religious affiliation” in the 2011 Census (most recent data available), up from 17% in 2001.

Download A Snapshot of Family Diversity in Canada (February 2018).

Infographic: Canada’s Families on the Farm

Family farms have played a significant role in Canada’s history, both in terms of the contributions that agriculture has provided in the development of local and provincial economies, and with regard to the role farming has played in shaping community and familial identities. Farming has a strong impact on the lives of families involved in the practice, as it is a unique experience that ties together notions of home, work, culture and kinship.

The evolution of farm families in Canada reflects some of the broader trends that are shaping the “family landscape” across the country, such as population aging, smaller families, a growing share of women in the labour force, the increased use of technology at work and a diversification of family income sources.

To explore Canada’s farm families, the Vanier Institute of the Family has published an infographic that features data from the 2016 Census of Agriculture.

Highlights include:

- Canada was home to more than 193,000 farms in 2016, down 5.9% from 2011.

- Canada was home to nearly 102,000 farm families in 2013, and the number of farm families decreased every year over the prior decade.

- The average age of farm operators increased from 47.5 years in 1991 to 55 years in 2016.

- The number of farm families with two family members rose from 43% in 2003 to 51% in 2013, while the share with five or more fell from 19% to 14%.

- 8.4% of all farms across Canada in 2016 reported having a written succession plan, and a family member was identified as the successor for 96% of these farms.

- In 2015, 57% of operators aged 60 and over were on farms that reported the use of technology, compared with 81% for those under the age of 40.

Download the Canada’s Families on the Farm infographic from the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Learn more in “Families on the Farm: A Portrait of Generations and Migrant Workers in Canada,” a chapter prepared by the Vanier Institute for Deep Roots, published by the United Nations as part the International Year of Family Farming.

Published on January 16, 2018

Grandparent Health and Family Well-Being

Rachel Margolis, Ph.D.

Download this article in PDF format.

Canada’s 7.1 million grandparents and great-grandparents make unique, diverse and valuable contributions to families and society, serving as role models, nurturers, historians, sources of experiential knowledge and more. As with the general population, the grandparent population in Canada is aging rapidly, sparking some concern in the media and public discourse about the potential impact of this “grey tsunami.”

However, despite being older, data show that the health of grandparents has improved over the past 30 years. This trend can positively impact families, since healthy grandparents can have a higher capacity to contribute to family life and help younger generations manage family responsibilities such as child care and household finances.

Improving grandparent health enhances their capacity to contribute to family life and help younger generations manage family responsibilities.

Canada is aging, and so are its grandparents

The aging of the grandparent population mirrors broader population aging trends across the country. According to the most recent Census in 2016, 16.9% of Canada’s population are seniors, nearly double the share in 1981 (9.6%) and the highest proportion to date. This growth is expected to continue over the next several decades: projections show that nearly one-quarter (23%) of Canadians will be 65 or older by 2031. Furthermore, the oldest Canadians (aged 100 and over) are currently the fastest-growing age group: there were 8,200 centenarians in 2016 (up 41% since 2011), and projections from Statistics Canada show that this group is likely to reach nearly 40,000 by 2051.

In this context, it’s perhaps no surprise that the overall grandparent population is also aging. The share of grandparents who are seniors grew from 41% in 1985 to 53% in 2011, and the share of grandparents who are aged 80 and older has grown even faster, nearly doubling from 6.8% in 1985 to 13.5% in 2011.

Life expectancy increases fuel grandparent population aging

One of the underlying factors fuelling the aging of the grandparent population is the fact that Canadians are living longer. According to Statistics Canada, life expectancy at birth has continued to rise steadily, reaching 83.8 years for women and 79.6 years for men in 2011–2013. This represents an increase of about a decade over the past half-century, with women and men gaining 9.5 years and 11.2 years, respectively, since the years 1960–1962.

In addition, more people are reaching seniorhood than in the past because of mortality declines at ages below age 65. Data from Statistics Canada shows that the average share of female newborns who can expect to reach age 65 rose from 86% for those born in 1980–1982 to 92% for those born in 2011–2013, while this share increased from 75% to 87% for males during the same period.

People are also living longer as seniors, as reflected in ongoing increases in life expectancy at age 65 – a useful measure of the well-being of older populations since it excludes mortality for those who do not reach seniorhood. According to estimates from Statistics Canada, life expectancy at age 65 in 2011–2013 was 21.9 years for women and 19 years for men – up by 3 years and 4.4 years, respectively, from 1980 to 1982.

Delayed fertility contributes to the aging of the grandparent population since it increases the age of transitioning into grandparenthood.

Another contributing factor to the aging of grandparents is the fact that on average, women are having children at older ages than in the past – a fertility trend that increases the age of transitioning into grandparenthood. The average age of first-time mothers has risen steadily since 1970, from 23.7 to 28.8 years in 2013. The number of first-time mothers aged 40 and older has also grown, rising from 1,172 in 1993 to 3,648 in 2013 (+210%). As more women postpone childbearing until later in life, their transition to grandparenthood will also likely occur later. Today’s new grandparents are baby boomers, a generation in which many women delayed fertility for education and work experience. Their children are also having children later, and the fertility postponement of two generations together is influencing the pattern of later entry into grandparenthood.

Despite the aging of grandparents, grandparenthood accounts for a growing portion of many people’s lives. Even though people are becoming grandparents later, they are living longer as grandparents. The longer period of time spent in the grandparent role can extend opportunities for forming, nurturing and strengthening relationships with younger generations. According to my recent research, the average number of years that someone can expect to spent as a grandparent given today’s demography in Canada is 24.3 years for women and 18.9 years for men – that’s approximately two decades in which they can continue to play a major role in family life.

Despite being older, grandparents are healthier

In addition to living longer, data from the General Social Survey (GSS) suggest that grandparents in Canada today are far more likely to report living in good health than in the past. The proportion who rate their health as “good/very good/excellent” has increased from 70% in 1985 to 77% in 2011, while the share reporting “fair/poor” health has fallen from 31% to 23%. Overall, the odds of grandparents reporting that they are in good health are 44% higher in 2011 than in 1985.

A number of trends have contributed to health improvements among grandparents and older Canadians in general over the past half-century. There have been significant advances in public health that have facilitated disease prevention, detection and treatment. Among other factors, this has led to major reductions in deaths from circulatory system diseases (e.g. heart disease), which has been one of the biggest contributors to gains in life expectancy among men over the past half-century.

Another factor contributing to improvements in the health of grandparents in Canada is the rising educational attainment of this population. Research shows that education can improve health both in direct and indirect ways throughout life. Direct impacts can include enhancing one’s health literacy, knowledge, interactions with the health care system and patients’ ability and willingness to advocate for themselves when engaging with health care providers. Indirect impacts can include an increase in one’s resources (e.g. income) or occupational opportunities (e.g. being less likely to have a physically demanding and/or risky job, and more likely to have a job with health benefits).

Education has been associated with greater health, which is significant because the share of grandparents who have completed post-secondary education has more than tripled over the past three decades.

These are important factors to consider in the Canadian context, since the share of grandparents who have completed post-secondary education has more than tripled over the past three decades, from 13% in 1985 to nearly 40% by 2011.

Healthy grandparents can facilitate family well-being

Grandparent health can have a significant impact on families. When a grandparent (or multiple grandparents) is living in poor health, families are often the first to provide, manage or pay for care that supports their well-being. This is particularly true for senior grandparents receiving care at home; the Health Council of Canada estimates that families provide between 70% and 75% of all home care received by seniors in Canada.

Data from the 2012 GSS show that nearly 3 in 10 Canadians (28%) reported providing caregiving to a family member in the past year, and aging-related needs were the most commonly cited reason for care (reported by 28% of caregivers). Grandparents accounted for 13% of all Canadians who received care, and they were also the most frequent recipients of young caregivers’ (aged 15 to 29) assistance, 4 in 10 of whom cited a grandparent as the primary recipient.

While 95% of caregivers say they’re effectively coping with their caregiving responsibilities, research has found that in some contexts, it can have a negative impact on their well-being, career development and family finances. This can be particularly true for the three-quarters of caregivers who are also in the paid labour force, accounting for more than one-third of all working Canadians.

On the other hand, when grandparents are living in good health, families can benefit in a variety of ways. In addition to the fact that it means they are less likely to require caregiving assistance, they are also more likely to be able to make positive contributions to family life, such as providing child care and contributing to family finances.

Grandparents provide child care to younger generations

Many grandparents play an important role in caring for their grandchildren, which can help parents in the “middle generation” manage their child care and paid work responsibilities. A number of economic, social and environmental trends have converged in recent decades that have increased the significant contributions they make to families with regard to child care.

Many grandparents play an important role in caring for their grandchildren, which can help parents in the “middle generation” manage their child care and paid work responsibilities.

Over the past four decades, the share of dual-earner couples in Canada has increased; in 1976, 36% of couples with children included two earners, a rate that nearly doubled to 69% by 2014. In more than half of these couples (51%), both parents worked full-time, which means they were more likely to rely on non-parental care for their children. This is supported by data from the 2011 GSS: while nearly half (46%) of all parents reported relying on some type of child care for their children aged 14 years and younger in the past year, the rate was higher (71%) for dual-earner parents with children aged 0 to 4 and children aged 5 to 14 (49%).

The evolution in family structure and composition across generations has also contributed to more families relying on non-parental care for their children. The share of lone-parent families has increased significantly over the past 50 years, rising from 8.4% of all families in 1961 to approximately 16% in 2016. Data from the 2011 GSS show that nearly 6 in 10 lone parents of children aged 4 and under (58%) report that they rely on non-parental care.

Sometimes grandparents are solely responsible for raising their grandchildren when no middle (i.e. parent) generation is present. The 2011 GSS counted 51,000 of these “skip-generation families” in Canada, which was home to 12% of all grandparents who live with their grandchildren. Some of those who live with their children are more likely than others to live in skip-generation homes, such as people reporting a First Nations (28%), Métis (28%) or Inuit (18%) identity (compared with 11% among the non-Indigenous population).

Lastly, many parents may rely on grandparents for help with child care if they can’t find quality, regulated child care spaces in their communities. In 2014, the availability in regulated, centre-based child care spaces was only sufficient for one-quarter (24%) of children aged 5 and under across Canada. While this is a significant increase from 12% in 1992, it still leaves more than 3 in 4 children in this age group without an available regulated child care space. The availability of child care (or a lack thereof) is significant, since it can affect whether or not parents in coupled families can both participate in the paid labour market.

The cost of child care can also lead parents to turn to grandparents for child care assistance. This is particularly true for families living in urban centres. One 2015 study on the cost of child care in Canadian cities, which used administrative fee data and randomized phone surveys conducted with child care centres and homes, found that the highest rates in Canada were in Toronto, where estimates showed median unsubsidized rates of $1,736 per month for full-day infant care (under 18 months of age) and $1,325 for toddlers (aged 1½ to 3).

Grandparent involvement can enhance child well-being

Regardless of the reason grandparents spend time with their grandchildren, their involvement in family life can benefit the well-being of children. Studies have shown that grandparent involvement in family life is significantly associated with child well-being – in particular, it has been associated with greater prosocial behaviours and school involvement. The benefits aren’t limited to children, either, as other research has shown that close relationships between grandparents and grandchildren can have a positive impact on mental health for both. Among First Nations families, grandparents have also been found to play an important role in supporting cultural health and healing among younger generations.

Research shows that grandparent involvement in family life is significantly associated with child well-being, including greater prosocial behaviours and school involvement.

The broader context of improving grandparent health is good news for many families, since their better health can make it easier to participate in activities with children and grandchildren, and research shows that these interactions with younger kin can be more rewarding in this context.

Many grandparents play an important role in family finances

Improvements in grandparent health can also enhance their capacity to engage in paid work, which can improve their own finances and facilitate contributions to younger generations.

Improvements in grandparent health also enhance their capacity to engage in paid work, which can improve their own finances and facilitate contributions to younger generations.

While there isn’t much recent data on the employment patterns of grandparents in Canada per se, rising rates of working seniors have been well documented over the past several decades. Between 1997 and 2003, the paid labour force participation rate for seniors ranged between 6% and 7%, but this has steadily increased to around 14% in the first half of 2017 (and an even higher rate of 27% for those aged 65 to 69). Since approximately 8 in 10 seniors in Canada are grandparents, it’s clear that a growing number of grandparents are working today.

The potential for grandparents to contribute to family finances through paid work can be particularly important for the 8% who live in multi-generational households. According to data from the 2016 Census, this is the fastest-growing household type, having grown in number by nearly 38% between 2011 and 2016 to reach 403,810 homes. Similar to patterns found among skip-generation families, this living arrangement is more common among Indigenous and immigrant families, which both represent a growing share of families in Canada.

Skip-generation living arrangements are more common among Indigenous and immigrant families, which both represent a growing share of families in Canada.

Data from the 2011 GSS showed that among the 584,000 grandparents living in these types of homes, more than half (50.3%) reported that they have financial responsibilities in the household. Some were more likely than others to contribute to family finances: rates were significantly higher for those living in skip-generation households (80%) and multi-generational households with a lone-parent middle generation (75%).

Opportunities are growing for grandparent–family relationships

While the aging of the general and grandparent population in Canada presents certain societal challenges, notably with regard to community care, housing, transportation and income security, their rising life expectancy and improving health present growing opportunities for individuals and families. Many grandparents already help younger generations with fulfilling family responsibilities, such as child care and managing family finances, and this will continue in the years ahead – a positive side of the story that is often lost in narratives about the “grey tsunami.”

As the health of grandparents has improved over the years, many have been able to enjoy a greater quantity and quality of relationships with younger family members. As families adapt and react to their evolving social, economic and cultural contexts, they will continue to play an important – and likely growing – role in family life for generations to come.

Rachel Margolis, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Western Ontario.

All references and source information can be found in the PDF version of this article.

Published on September 5, 2017

Infographic: Modern Couples in Canada

Just as families have evolved across generations, so too have the couple relationships that are a major part of Canada’s “family landscape.” This perpetual change is both a reflection of and a driving force behind some of the evolving social, economic, cultural and environmental forces that shape family life.

Dating, marriage, cohabitation, common-law relationships – the ways people choose to come together, or decide to move apart, are as diverse as the couples themselves. There are, however, some broad trends being witnessed across the country, with family structures diversifying, people forming couple relationships at later ages and family finances taking on a more egalitarian structure.

Using new data from the 2016 Census, the Vanier Institute of the Family has published an infographic on modern couples in Canada.

Highlights include:

- In 2016, married couples accounted for 79% of all couples in Canada, down from 93% in 1981.

- One-quarter of “never-married” Canadians say they don’t intend to get married.

- In 2016, 21% of all couples in Canada were living common-law, up from 6% in 1981.

- The share of twentysomething women (37%) and men (25%) living in couples has nearly halved since 1981 (falling from 59% and 45%, respectively).

- In 2016, 12.4% of all couple families in Canada with children under 25 were stepfamilies, down slightly from 12.6% in 2011.

- There are 73,000 same-sex couples in Canada, 12% of whom are raising children.

- 1 in 5 surveyed Canadians reported in 2011 that their parents are separated or divorced, up from 10% in 2001.

- The share of people living in mixed unions nearly doubled between 1991 and 2011, from 2.6% to 4.6%.1

- 69% of couples with children were dual-earner couples in 2014, up from 36% in 1976.

Download the Modern Couples in Canada infographic from the Vanier Institute of the Family

Notes

- Statistics Canada defines a mixed union as “a couple in which one spouse or partner belongs to a visible minority group and the other does not, as well as a couple in which the two spouses or partners belong to different visible minority groups.”

A Snapshot of Population Aging and Intergenerational Relationships in Canada

Canada’s population is aging rapidly, with a higher share of seniors than ever before. While this can present some societal challenges, it also provides growing opportunities for intergenerational relationships, since younger people have a greater likelihood of having more seniors and elders in their lives. Population aging has an impact not only on family relationships, but also on the social, economic, cultural and environmental contexts in which families live.

Using new statistics from the 2016 Census, A Snapshot of Population Aging and Intergenerational Relationships in Canada explores the evolving demographic landscape across the country through a family lens. As the data shows, Canadians are getting older, and “seniorhood” is a growing life stage – a time when many of our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents are continuing to play important roles in our families, workplaces and communities.

Highlights include:

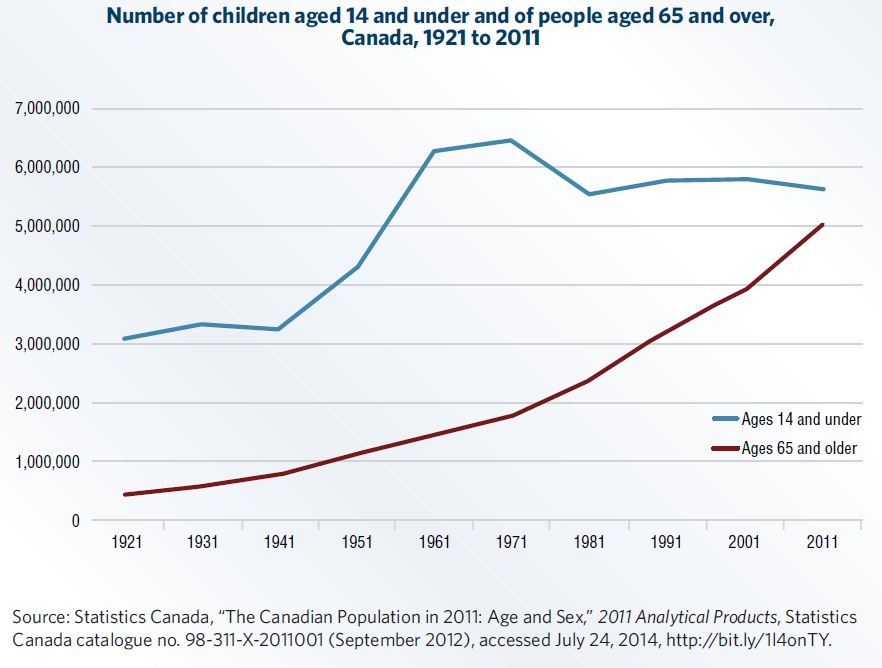

- There are more seniors than ever before in Canada. More than 5.9 million people in Canada are aged 65 and older – up 20% since 2011 and now outnumbering children (5.8 million).

- Nunavut is the youngest region in Canada. Children account for one-third (33%) of the population in Nunavut.

- We’re more likely to become seniors than in the past. In 2012, nine in 10 Canadians were expected to reach age 65, up from six in 10 in 1925.

- The number of multi-generational households is growing. In 2011, 1.3 million people in Canada lived in multi-generational homes, up 40% since 2001.

- Working seniors are on the rise. The labour market participation rate of seniors more than doubled since 2000, from 6.0% to 14% in 2016.

- Canada’s aging population affects family finances. An estimated $750 billion is expected to be transferred to Canadians aged 50 to 75 over the next decade.

This bilingual resource will be updated periodically as new data emerges. Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter to find out about updates, as well as other news about publications, projects and initiatives from the Vanier Institute.

Download A Snapshot of Population Aging and Intergenerational Relationships in Canada from the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Timeline: Fifty Years of Men, Work and Family in Canada

Over the past half century, fatherhood in Canada has undergone a significant evolution as men are increasingly sharing the “breadwinning” role, embracing caring responsibilities and integrating their responsibilities at home, at work and in their communities.

To explore these trends and the social, economic, cultural and environmental contexts that shape – and are shaped by – fatherhood and family relationships, we’ve created a 50-year timeline for Father’s Day 2016. Some highlights include:

- More fathers are taking time off to care for their newborn children. More than one-quarter (27%) of all recent fathers in Canada reported in 2014 that they took (or intended to take) parental leave, up from only 3% in 2000.

- The number of “stay-at-home” fathers is on the rise. Fathers accounted for approximately 11% of stay-at-home parents in 2014, up from only 1% in 1976.

- Fathers of young children are absent from work more frequently for family-related reasons. Fathers of children under the age of 5 report missing an average 2.0 days of work in 2015 due to personal or family responsibilities, up from 1.2 days in 2009.

- Fewer “lone fathers” are living in low income. In 2008, 7% of persons in lone-parent families headed by men lived in low income, down from 18% in 1976.

- Fathers are increasingly helping with housework. Men who report performing household work devoted an average 184 minutes on these tasks in 2010, up from 171 minutes in 1998.

- Fathers with flex are more satisfied with their work–life balance. More than eight in 10 (81%) full-time working fathers with children under age 18 who have a flexible schedule reported in 2012 being satisfied with their work–life balance, compared with 76% for those without a flexible schedule.

- A growing number of children find it easier to talk to dad. In 2013–2014, 66% of 11-year-old girls and 75% of boys the same age say they find it easy to talk to their father about things that really bother them, up from 56% and 72%, respectively, two decades earlier.

This bilingual resource is a perpetual publication, and it will be updated periodically as new data emerges. Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter to find out about updates, as well as other news about publications, projects and initiatives from the Vanier Institute.

Enjoy our new timeline, and happy Father’s Day to Canada’s 8.6 million dads!

Download the Fifty Years of Men, Work and Family in Canada timeline.

Intergenerational Relations and Societal Change

Donna S. Lero, Ph.D.

In order to better understand families’ experiences and aspirations, it is crucial to understand the context in which families and their individual members live. Families are society’s most adaptable institution, constantly reacting to cultural, social and economic forces while affecting those same forces through their thoughts and behaviour. A number of recent and projected demographic and social trends are expected to have a significant impact on relationships between different generations, and exploring these shifting contexts can provide valuable insight into how intergenerational relations are affected and the potential impacts they have on social cohesion within families and in different generations – the question of intergenerational equity.

Population aging increases caregiving needs and lengthens intergenerational relationships

Population aging is a feature of most developed societies, a result of low fertility rates and people living longer. These two forces are transforming the traditional population pyramid to a more rectangular shape, shifting the size and proportion of older populations in society. In Canada, the proportion of the population 65 years and over increased from 8% in 1971 to 15.3% in 2013, and will be close to 25% in 2050.

Canada is not alone in this regard: across Europe, the proportion of the population aged 80 and over is expected to increase from 4% in 2010 to close to 10% by 2050, with substantially higher proportions in Germany, Italy, Japan and Korea. These trends have major implications for government planning in order to address pensions, health care costs, home and residential care, and supports for family caregivers.

Of increasing concern is the projection that there will be more individuals in their advanced years, with fewer children and grandchildren to provide care and assistance. Using census data, Janice Keefe and her colleagues have projected that the number of elderly people needing assistance in Canada will double in the next 30 years and that the decline in the availability of children will increase the need for home care and formal care, particularly over the longer term. Notably, it is projected that close to one in four elderly women may not have a surviving child by 2031.

Baby boomers continue to be the largest population group, still dominating the workforce, but starting to reach traditional retirement age. This group is experiencing caregiving pressures for aging parents and facing significant challenges managing paid work and care. In 2007, 37% of employed women and 29% of employed men aged 45–64 were caregivers, and those proportions are set to increase. At the same time, an estimated 28% of caregivers still have one or more children aged 18 or younger at home.

A recent trend in Canada and the U.S. is an increasing proportion of “older workers” typically defined as 55 years and older. Still healthy and capable, many people in their 60s and 70s are either prolonging careers or taking new jobs, often to supplement savings and/or limited pension income that will not last through their full retirement years. Canadian federal, provincial and territorial ministers responsible for seniors have identified the promotion of workplace supports for older workers, including supports to balance work and care, as one of two priority areas for the coming years.

In addition to being the largest population group, baby boomers have encountered different social circumstances growing up than their parents did. In the U.S. and Canada, they have been influenced by changes in women’s rights and roles, the sexual revolution, higher rates of divorce and enhanced educational opportunities. The longevity of the boomers’ relationships to their siblings and to aging parents has been described as “unprecedented” and their experiences as caregivers to their aging parents and their expectations and capacities as they age will significantly influence policy developments related to pensions, health care and long-term care.

Baby boomers have also had particularly close relationships with their children, and a poor economy that is limiting their young adult children’s opportunities and contributing to delayed family formation and careers is a source of significant concern. As a result, many boomers are concurrently providing substantial care to aging parents with chronic illnesses; have significant ties to siblings who, like themselves, may be carefully monitoring their retirement savings and possibly planning to extend their involvement in the labour force; and are providing support to their own children. Siblings, parents and grandparents today have a greater amount of time together than in previous generations. Vern Bengston has described this as a positive trend at the micro level, as it creates prolonged periods for shared experiences and opportunities for exchange that can strengthen intergenerational solidarity, despite a general societal trend at the macro level toward weakening norms governing intergenerational relations.

Greater diversity in family forms increases the role of “chosen families”

Baby boomers and their adult children have experienced higher rates of separation and divorce, remarriage, blended families and common-law arrangements than previous generations. An increase in same-sex unions and marriages is also evident. These complex and diverse relationships can result in what Karen Fingerman describes as “complex emotional, legal and financial demands” from former partners, estranged parents and relatives such as former in-laws or stepchildren. While complicating the nature of relationships and creating ambiguous expectations for exchange and support, Bengston suggests that the diverse network of relationships can provide a broader “latent kin network” (sometimes referred to as “fictive kin”) that can provide additional support when needed.

This latent kin network, which increasingly includes close friends who function “like family,” may substitute for or augment the support available from fewer or estranged family members, who may be geographically distant and/or have weaker ties over time. Interesting policy questions emerge when legal rights, financial benefits and other supports that were developed with heterosexual nuclear families in mind do not extend to the broader diversity and complexity of family forms evident in modern societies.

Longer transitions for youth into the labour market increases intergenerational dependency

A variety of cultural, social and economic conditions has been identified as factors that are contributing to a prolonged transition to adulthood in North America. Evidence of this lengthy and sometimes precarious transition to financial independence includes young adults’ extended involvement in education, a higher proportion living at home with their parents than previously, delayed and difficult entries into the job market and into long-term career paths, and delayed conjugal formation and child-bearing.

These processes have been occurring over a period of time, but are increasingly evident and in contrast to the experiences of previous generations at the same age. Young people’s experiences have led to longer periods of financial dependency on parents at the micro level and they are contributing to emerging concerns about intergenerational equity at a broader social level.

Given increasingly tight job prospects and the importance of education for good jobs in a knowledge-based economy, more young adults are turning to post-secondary education programs and the gaining of credentials as a way to increase employment opportunities and earnings. In Canada and other OECD countries, almost half of those in their early 20s are attending educational institutions full-time. Consequently, the tendency to stay in school longer, in conjunction with the extended time it takes to obtain employment in a related field, is increasing the average duration of the school-to-work transition.

Although post-secondary education adds human capital for individuals and for society, the benefits of a university degree may not be evident when graduates have difficulty finding suitable employment, as has been the case in recent years. Those with only a high school education face an even more difficult time finding a job that pays a living wage.

A complicating factor for many university graduates in Canada and the U.S. is the level of student debt. According to a 2013 Bank of Montreal student survey, current university students in Canada anticipate graduating with over $26,000 in debt. Student debt levels have escalated, particularly in the last decade, as tuition fees have increased – a function of limited government funding. Current student loan programs require that graduates begin repayment almost immediately after graduation. In addition to the anxiety accumulated debt produces for students, it is a substantial impediment to gaining financial independence from parents and it contributes to delaying marriage, child-bearing, home ownership and other purchases.

A serious concern, reflected in a growing number of current news reports, is the challenge young adults have finding jobs that afford a living wage. As described by James Côté and John Bynner, “Today’s young people face a labour market characterized by an increasing wage gap with older workers, earnings instability, more temporary and part-time jobs, lower-quality jobs with fewer benefits and more instability in employment.” These authors go on to state an additional concern: that “the decreased utility of youth labour in the context of this job competition has produced a growing age-based disparity of income (emphasis mine), contributing to increasingly prolonged and precarious transitions to financial independence.”

Statistics Canada has reported that, in 2011, 42.3% of young adults aged 20–29 lived in the parental home, either because they had never left it or because they returned home after living elsewhere. Most telling is the finding that, among 25- to 29-year-olds, one-quarter (25.2%) lived in their parental home in 2011, more than double the 11.3% observed in 1981.

The Pew Research Center’s report on the millennial generation in the U.S. (aged 18–33) has noted marked generational changes in the age of marriage. In 2013, just 26% of the millennial generation was married, compared to 48% of baby boomers (aged 50–64) when they were the same age. The current pattern of delayed child-bearing evident in Canada is a natural consequence. People are having fewer children (if any) and having them later. Beginning in 2005, fertility rates of mothers in their 30s has outnumbered the rates observed among mothers in their 20s. In 2011, 2.1% of all first-time mothers who gave birth that year were in their 40s, up from 0.5% in 1991.

Higher rates of immigration lead to greater diversity in intergenerational relationships

Rates of international immigration have increased dramatically in recent decades, spurred by greater opportunity to do so and economic needs. For many years, Canada has relied on international migration as a source of population and labour force growth. Resettlement policies and services aid in the transition of newcomers, promoting the learning of English or French, enhancing access to health and community services, and facilitating a smoother transition to the labour force.

Although newcomers may be more dependent on immediate family members for support, they experience wider discrepancies in expectations between generations in the family as a result of acculturation. For example, cultural and religious values may place particular emphasis on respect for elders and filial obligations to provide support, yet studies of immigrants from diverse backgrounds suggest that immigration and acculturation can place significant strains on newcomer families. This can particularly be the case when aging parents expect filial support and reject formal support and their adult children face economic challenges that require their involvement in precarious employment, multiple jobs or work that involves long hours or non-standard schedules.

In summary, multiple factors, including population aging, low fertility rates, increasing diversity in family forms, delayed transitions to financial independence and high rates of international immigration, affect the nature of intergenerational relations at both the micro and macro levels. As the population in Canada continues to age, generations will share relationships for longer periods of time. Longer intergenerational relationships mean that families (whether related by blood or marriage or “chosen” circles of kin) will have a greater amount of time in which members can provide support and care for each other, regardless of the context in which they live. Challenges include ensuring that supports are available that sustain caring relationships over time, especially in more complex circumstances and in a context of limited and fragmented supports for caregiving.

Dr. Donna S. Lero is a Professor in the Department of Family Relations and is the Jarislowsky Chair in Families and Work at the University of Guelph. She leads a program of research on public policies, workplace practices and community supports in the Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being, which she co-founded.