Gaëlle Simard-Duplain is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Economics at Carleton University. Her research focuses on the determination of health and labour market outcomes. She is particularly interested in the interaction of policy and family in mitigating or exacerbating inequalities, through both intrahousehold family dynamics and intergenerational transmission mechanisms. Her work predominantly uses administrative data sources, sometimes linked to survey data, and quasi-experimental research methods. Gaëlle holds a PhD in Economics from the University of British Columbia.

Topic: COVID-19

Andrea Doucet

Andrea Doucet is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Gender, Work, and Care, Professor in Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies at Brock University, and Adjunct Professor at Carleton University and the University of Victoria (Canada). She has published widely on care/work policies, parental leave policies, fathering and care, and gender divisions and relations of paid and unpaid work. She is the author of two editions of the award-winning book Do Men Mother? (University of Toronto Press, 2006, 2018), co-author of two editions of Gender Relations: Intersectionality and Social Change (Oxford, 2008, 2017), and co-editor of Thinking Ecologically, Thinking Responsibly: The Legacies of Lorraine Code (SUNY, 2021). She is currently writing about social-ecological care and connections between parental leaves, care leaves, and Universal Basic Services. Her recent research collaborations include projects with Canadian community organizations on young Black motherhood (with Sadie Goddard-Durant); feminist, ecological, and Indigenous approaches to care ethics and care work (with Eva Jewell and Vanessa Watts); and social inclusion/exclusion in parental leave policies (with Sophie Mathieu and Lindsey McKay). She is the Project Director and Principal Investigator of the Canadian SSHRC Partnership program, Reimagining Care/Work Policies, and Co-Coordinator of the International Network of Leave Policies and Research.

Barbara Neis

Barbara Neis (PhD, C.M., F.R.S.C.) is John Lewis Paton Distinguished University Professor and Honorary Research Professor, retired from Memorial University’s Department of Sociology. Barbara received her PhD in Sociology from the University of Toronto in 1988. Her research focuses broadly on interactions between work, environment, health, families, and communities in marine and coastal contexts. She is the former co-founder and co-director of Memorial University’s SafetyNet Centre for Occupational Health and Safety and former President of the Canadian Association for Work and Health. Since the 1990s, she has carried out, supervised, and supported extensive collaborative research with industry in the Newfoundland and Labrador fisheries including in the areas of fishermen’s knowledge, science, and management; occupational health and safety; rebuilding collapsed fisheries; and gender and fisheries. Between 2012 and 2023, she directed the SSHRC-funded On the Move Partnership (www.onthemovepartnership.ca), a large, multidisciplinary research program exploring the dynamics of extended/complex employment-related geographical mobility in the Canadian context, including its impact on workers and their families, employers, and communities.

Yue Qian

Yue Qian (pronounced Yew-ay Chian) is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. She received her PhD in Sociology from Ohio State University. Her research examines gender, family and work, and inequality in global contexts, with a particular focus on North America and East Asia.

Research Snapshot: Children’s Digital Play as Collective Family Resilience in the Face of the Pandemic

Highlights of a study of how digital play helped foster children’s agency, creativity, and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

Research Snapshot: Parents, Homeschooling, and Relationship Conflict During COVID-19

Highlights from a study on how providing homeschooling during COVID affected parents

Paternity Benefit Use During COVID-19: Early Findings from Quebec

Sophie Mathieu, PhD, and Marie Gendron, CEO of the Conseil de gestion de l’assurance parentale, share recent findings on paternity leave uptake during pandemic in Quebec.

Divorce in Canada: A Tale of Two Trends

Nathan Battams shares new findings on divorce trends in Canada over the last 30 years.

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Newcomer and Refugee Mothers in Canada – Final Report

Final report on COVID-19 IMPACTS: Newcomer and Refugee Mothers in Canada survey.

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Family Therapists Survey – Final Report

Final report on the findings from the COVID-19 IMPACTS: Family Therapists Survey.

Stories Behind the Stats: Becoming a New Dad During Lockdown

A conversation with a new dad about his journey into fatherhood during lockdown.

In Brief: COVID-19 IMPACTS Through a Gender-based Lens

Diana Gerasimov summarizes new findings on the gendered impacts of the pandemic.

Caregiving During COVID: What Have We Learned? (Video)

Alex Foster-Petrocco shares takeaways and highlights from a recent webinar on caregiving and technology during COVID-19.

REVIEW: Mothers, Mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from a Pandemic

Alex Foster-Petrocco reviews a new book exploring the experiences of mothers during COVID-19.

Report: Family Well-being in Canada

New report on well-being in Canada co-authored by staff from Statistics Canada and the Vanier Institute.

In Brief: COVID-19 IMPACTS on Families Living with Disabilities

Vanier Institute’s In Brief Series: Mobilizing Research on Families in Canada

Diana Gerasimov

March 9, 2021

STUDIES:

Yang, F., K. Dorrance and N. Aitken. “The Changes in Health and Well-being of Canadians with Long-term Conditions or Disabilities Since the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45-28-0001 (October 7, 2020). Link: http://bit.ly/3bXpkSh.

Arim, R., L. Findlay and D. Kohen. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Canadian Families of Children with Disabilities,” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45-28-0001 (August 27, 2020). Link: http://bit.ly/2QSNVxH.

Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected many Canadians’ physical and mental health,1 including limiting their access to services they may have otherwise reached out to for support. This can have a significant impact on those living with disabilities or long-term conditions, who are more likely to use health services on a regular basis and whose situation may be compounded by isolation and distance from familiar, informal social support.

In a recently published data from Statistics Canada, Canadians living with disabilities or long-term conditions who participated in a crowdsourced survey, from June to July 2020, reported declining health and mental health, as well as disruptions to health services. Variations in the general health of participants depend on the type of disability or long-term condition that individuals experience.

- 48% of participants living with disabilities or chronic conditions reported that their health was “somewhat worse” or “much worse” since before the pandemic.

- 64% of participants with cognitive conditions reported that their health had gotten “much” or “somewhat” worse compared with before the pandemic.

- 60% of individuals with mental health conditions reported that their overall health had gotten “much” or “somewhat” worse compared with before the pandemic.

- 48% of participants with hearing conditions reported their health to have stayed about the same.

- 73% of participants with mental-health related conditions reported “much worse” or “somewhat worse” mental health.

- 57% of participants with disabilities or chronic conditions self-rated their overall mental health as having declined since the beginning of the pandemic, while 36% reported that their mental health had not changed and 7% reported an improvement in their mental health (“somewhat better” or “much better”).

- 44% participants with hearing conditions reported consistent mental health since before the pandemic.

Families of children with disabilities

Another crowdsourced survey, which explored the experiences of parents of children living with disabilities, found that they were more likely to express concern for their children regarding their child’s mental health, anxiety and emotions, academic success and the impact of social isolation.

- 60% of parents of children with disabilities were concerned for their child’s mental health compared with 43% of parents with children without disabilities.

- 76% of parents of children with disabilities were very concerned about regulating their child’s anxiety and emotions, compared with 57% of parents of children without disabilities.

- 58% of parents of children with disabilities or long-term conditions were very concerned for their child’s academic success compared with 36% of parents of children without disabilities.

- 6 in 10 parents of children with disabilities were very concerned about social isolation compared with 5 in 10 parents of children without disabilities.

Diana Gerasimov holds a bachelor’s degree from Concordia University in Communication and Cultural Studies.

Note

- Learn more about the impact of COVID-19 on mental health in Family Finances and Mental Health During the COVID‑19 Pandemic and Do Adults in Couples Have Better Mental Health During the COVID‑19 Pandemic?

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Family Life, Traditions and Rituals

February 26, 2021

While COVID-19 has affected families across Canada and disrupted many of our routines, roles and relationships, it hasn’t stopped family life. Whether we are connecting to celebrate milestones or providing support in difficult times, people are finding diverse and creative ways to keep doing what families do – often with some help from technology.

According to a recent Leger survey,1 some families have taken their family traditions, celebrations and gatherings – both joyous and sad – through video conferencing platforms such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. While the experience may not be the same as hugging and talking to our loved ones in person, these adaptations are allowing many families to continue to smile, laugh, cry and grieve together. The data show that most, but not all, find them less meaningful than in person but that, for many, it is better than nothing.

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Marriage and weddings

With public health measures restricting in-person gatherings across Canada, many couples in the early months of the pandemic who had planned to get married postponed their wedding plans, but with continuing restrictions on social gatherings, some have gone ahead, “tying the knot” virtually, connecting with their families and friends using video conferencing platforms.

The survey found that…

- In the past year, 7% of respondents had participated in a wedding on a video conferencing platform (e.g. Zoom, Microsoft Teams).

- Those with children in the household (13%) were more than twice as likely as those without children at home (5%) to have participated in an online wedding.

- The likelihood of having participated in an online wedding decreased with age:

- 12% of those aged 18 to 34

- 8% of those aged 35 to 54

- 2% of those aged 55 and older

- Among those who had participated in an online wedding, a slight majority said it was less meaningful than in person; those with children and younger respondents were more likely to report it as more meaningful:

- Slightly over half (54%) said it was less meaningful, and 25% said it was “about the same.” However, 21% found it “more meaningful.”

- Respondents with children in the household (32%) were more than twice as likely than those without children at home (12%) to report it as a more meaningful experience.

- The likelihood of saying it was more meaningful dropped sharply with age:

- 32% of those aged 18 to 34

- 14% of those aged 35 to 54

- 0% of those aged 55 and older

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Grief and loss

Family grieving has also been taking place online, with many families hosting funerals on video conferencing platforms (e.g. Zoom, Microsoft Teams). Respondents in the survey were twice as likely to report having participated in an online funeral (14%) than an online wedding (7%).

- 1 in 7 surveyed Canadians (14%) said they have participated in a funeral on a video conferencing platform in the past year.

- Respondents with children in the household (16%) were more likely than those without children at home (13%) to have participated in an online funeral.

- The likelihood of having participated in an online funeral increased with age:

- 12% of those aged 18 to 34

- 14% of those aged 35 to 54

- 16% of those aged 55 and older

- When those who had attended an online funeral were asked about how meaningful their experience was compared with an in-person funeral:

- More than one-third said it was “about the same” (25%) or “more meaningful” (9%), while the remaining two-thirds (66%) said it was “less meaningful.”

- Respondents with children in the household (14%) were twice as likely as those without children at home (7%) to report it as a more meaningful experience.

- The youngest age group was the most likely to report it being more meaningful:

- 17% of those aged 18 to 34

- 4% of those aged 35 to 54

- 8% of those aged 55 and older

Adaptability and creativity will continue to play an important role in keeping families connected under COVID-19. While this survey showed that families clearly miss their in-person gatherings, these virtual adaptations of weddings, funerals and other family gatherings will likely persist in some format post-COVID (perhaps alongside in-person events), as they allow for family and friends at a distance to stay connected and experience important family events together.

Note

- A survey was conducted by Leger for the Association for Canadian Studies on February 12 and 13, 2021 with 1,535 respondents. While no margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample, for comparative purposes the national sample of 1,535 Canadians would have a margin of error of ±2.5%, 19 times out of 20.

Celebrating Chosen Family Within the LGBTQ+ Community

Gaby Novoa

February 18, 2021

This February 22, 2021 is Chosen Family Day, a national observance of the significant relationships among those in the LGBTQ+ community.1, 2 Families formed by choice, and with intention, play a vital role in the lives of many LGBTQ+ people, where close relationships provide care, affirmation and a sense of belonging.

Research shows that marginalization due to one’s sexual orientation or gender identity has been linked to higher rates of family rejection, mental health challenges, substance abuse and exposure to violence among LGBTQ+, compared with their heterosexual and/or cisgender counterparts.3 These vulnerabilities are further amplified for those with intersectional identities, such as one’s race, class, religion or dis/abilities. Chosen families, friendships and positive community connections are therefore essential, as social connectedness is a key factor in well-being and resilience.4

Chosen families face more barriers yet serve many of the same functions of biological families

Fondation Émergence, a non-profit organization in Quebec that supports and serves the LGBTQ+ community through education and awareness-building, champions the importance of chosen family.5 Julien Rougerie, Program Manager with the organization, asserts that the roles within chosen and biological families are often identical: providing love, support, care and connections.

The difference for family who are not blood-related, however, is that their roles are often impeded by more barriers, such as the lack of formal recognition of such ties as valid or “legitimate.” Research has shown, for example, that LGBTQ+ seniors in long-term care homes are sometimes not able to get access or certain permissions for their loved ones when protocols and regulations are not inclusive to those who do not fall under “traditional” conceptualizations of a family member. Moreover, the fear of disclosing one’s sexual orientation can sometimes prevent an individual from identifying their partner or spouse. When institutions, such as health care or long-term care systems, do not acknowledge these diverse family formations, they block pathways of necessary care and connection.

One study found that, apart from their partner, 59% of lesbian, gay and bisexual adults aged 50 and over indicated that friends are the first people they contact in emergencies, whereas only 9% say that they contact a “family member.”6 Rougerie notes that LGBTQ+ older adults commonly share experiences of estrangement or distance from their biological families, as they grew up in sociocultural and political contexts in which there existed more stigma and sanctions around queerness. Reliance and interdependence with chosen family therefore take on additional significance among LGBTQ+ older adults, whose chosen family often become their caregivers in later life.

Chosen family and well-being are interconnected

In preparing for Chosen Family Day, the Vanier Institute asked people who identify as LGBTQ+ to share what these connections mean to them. Many of the responses and reflections highlighted themes of solace, security and strength:

“Chosen family is moving forward in my life. It’s feeling like I have agency in the experience of fraternity, trust and companionship. It’s building networks that are strong, like the points and spirals on a spider web.”

“To me, chosen family is the community of support with which you surround yourself. It’s the relationships you hold closest – whatever their nature is – and where you feel unquestionably at home.”

“Chosen family is wholehearted, wholesome, safe, strength, shared resources, shared emotions, uplifting habits, community, shared creation (such as through food), communion and ritual.”

“For me, chosen family is a group of people that you can turn to when you face hardships or have something to celebrate, and they can be there for you without judgement, especially when it comes to queer aspects of life such as dating or gender identity. It’s not really about seeing each other all the time or even being best friends, it’s knowing that you can confide and find comfort in someone and be assured that they love you AND your queerness, not despite it.”

“Chosen family mean there’s always an extra chair, and it’s for you.”

“Chosen family to me is reclaiming something that you didn’t have before.”

“Having a chosen family is an extension of self-love. The active choice to surround myself with people who love and support me is the most significant way that I can appreciate and value myself.”

“Chosen family is like a big family gathering but without uncomfortable chairs, heavy air (heavy with secrets) and weird unspoken rules about when to speak. Instead, we are talking about a web of people who bob in and out of my life. I look to them and they look out for me. It’s not all smooth sailing – they teach me hard lessons (like how to avoid jealousy and how to deal with grief). In the light moments and in the rough ones, I’m so grateful for my chosen family.”

“Chosen family is a place without judgement. It’s where you feel safe and true to yourself. It’s a place ‘where you don’t have to shrink yourself, to pretend or to perform.’”7

“Chosen family are those who help you sustain an environment of peace where you can show up as your authentic self.”

“To me a chosen family is one connected above all by trust and a kind of loyalty that is easy because it recognizes and anticipates change and growth.”

Special thanks to all those who took the time to share.

Responses have been edited for punctuation.

Gaby Novoa, Families in Canada Knowledge Hub, Vanier Institute of the Family

Notes

- Friends of Ruby – an organization focused on supporting the progressive well-being of LGBTQI2S youth through social services and housing – launched Chosen Family Day in February 2020. Link: https://www.friendsofruby.ca/.

- Nathan Battams, “In Conversation: Lucy Gallo on Chosen Family Day and LGBTQI2S Youth,” The Vanier Institute of the Family (February 2020).

- Jonathan Garcia et al., “Social Isolation and Connectedness as Determinants of Well-Being: Global Evidence Mapping Focused on LGBTQ Youth,” Global Public Health (October 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/3p8BCMg.

- Ibid.

- Fondation Émergence. Link: https://bit.ly/3aeMS5F.

- Fondation Émergence, “Ensuring the Good Treatment of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Older Adults” (2018). Link: https://bit.ly/3jKQsaQ.

- The quoted words are lyrics from the song “Family” by Blood Orange.

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Couple Relationships in Canada

Ana Fostik explores the family impacts of uncertainty and economic downturn on couple relationships in Canada.

COVID-19 IMPACTS: Retirees and Family Finances in Canada

Edward Ng, PhD

September 3, 2020

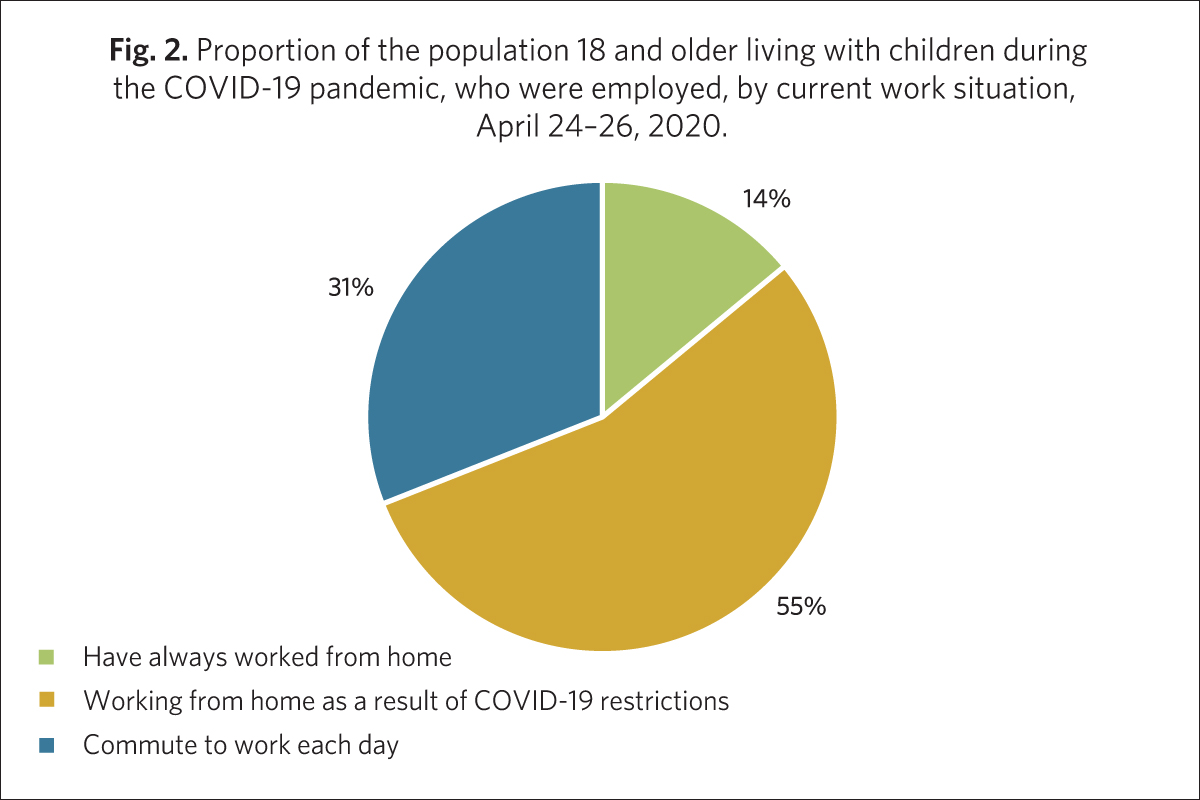

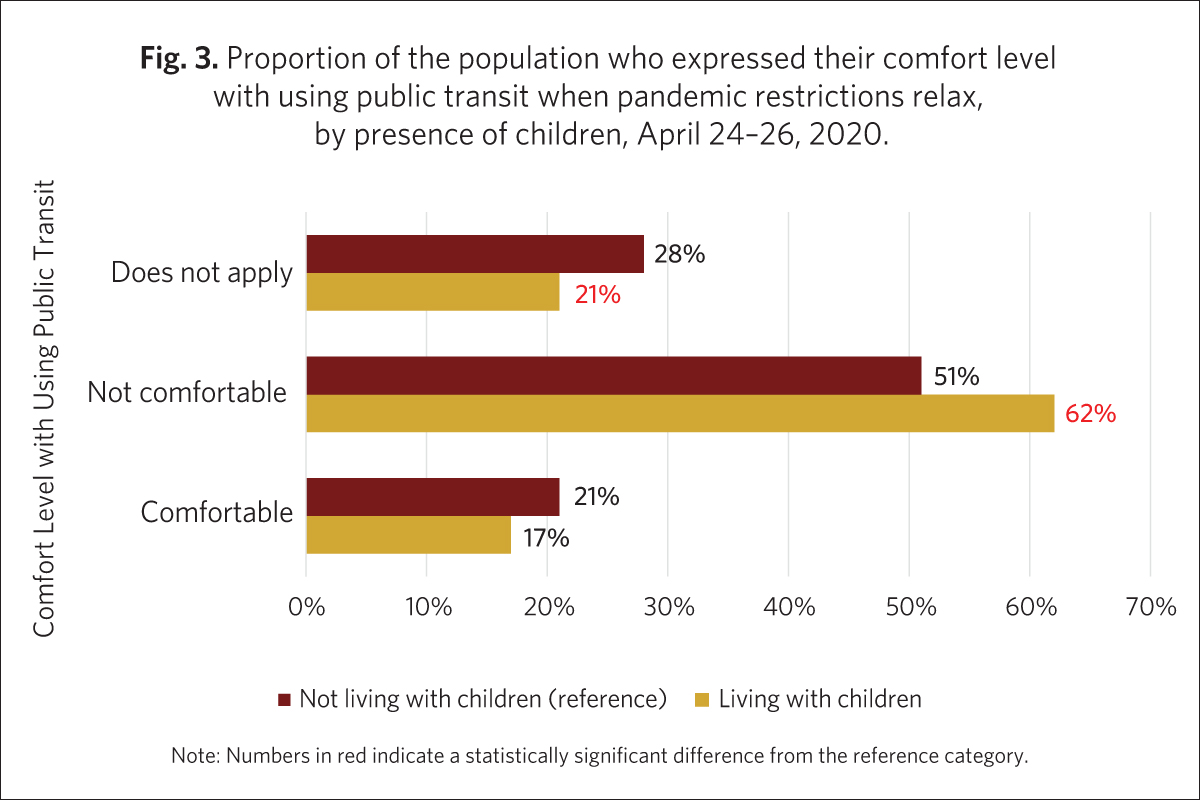

COVID-19 has had a major impact on the labour market, work–life and family finances in Canada. Amid the public health measures and economic lockdown, many organizations and businesses across the country rapidly laid off employees and/or transitioned employees to teleworking. As a result, the unemployment rate increased from 8% to 14% between March and May 2020, reaching the highest figure recorded since comparable data became available in 1976.1 A survey conducted April 10–12, 2020 by Leger, the Association for Canadians Studies (ACS) and the Vanier Institute found that more than one-third of Canadians aged 18 and older were financially impacted due to COVID-19 (i.e. lost their job temporarily or permanently, or experienced pay or income losses).2

Within many families, this context of uncertainty in the labour market can have a major impact on aspirations, such as buying a home, having a child3 or pursuing post-secondary education. Retirement has also been affected, with pre-retirees and retirees alike adapting and reacting to the evolving context to support family. Retired people are in a unique situation, however, when it comes to the financial impact of COVID-19, as they are not in the labour force, and those who are seniors have access to other income supports. As their capacity to provide financial support to family is shaped by their own finances, understanding their unique realities and experiences will help shed light on this aspect of COVID-19 impacts on families in Canada.

Retirement plans shaped by family finances and available supports

While a growing share of Canadians are working past their 50s and beyond the traditional retirement age of 65, the retired population has grown overall as population aging has continued. According to Statistics Canada, the average age at retirement for all workers in Canada was 64.3 in 2019. That said, many older Canadians continue to work well into their 60s and beyond. In 2017, nearly one-third of Canadians aged 60 and older said that they worked (or wanted to work) in the previous year, half (49%) of whom did so “out of necessity.”4

Prior to COVID-19, many Canadians expressed concern about their financial preparedness for retirement. According to the 2019 Canadian Financial Capability Survey, 69% of pre-retired Canadians are preparing financially for retirement, on their own or through a workplace pension plan.5 But more than one-third of surveyed Canadians aged 55 and older reported are concerned they don’t have enough savings (37%) and/or that they will be able to cover health care costs as they age (34%).6

Retirees who are seniors have access to income support through government pension payments, available to all Canadians at age 65 who have lived in the country for at least 10 years. On top of privately arranged retirement schemes and/or personal retirement savings or investments, public income programs for seniors, such as the Old Age Security (OAS) program, the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) and the Canada/Quebec Pension Plan, provide senior retirees in Canada with fixed and relatively stable income sources that can help protect them against economic instability, such as the economic shock resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In May 2020, in response to the financial stress placed on retirees and seniors, the federal government announced additional financial support for seniors as a one-time payment of $500 for individuals who receive both the OAS and the GIS to offset additional costs from COVID-19.7

Retiree investments impacted, but overall family finances less affected

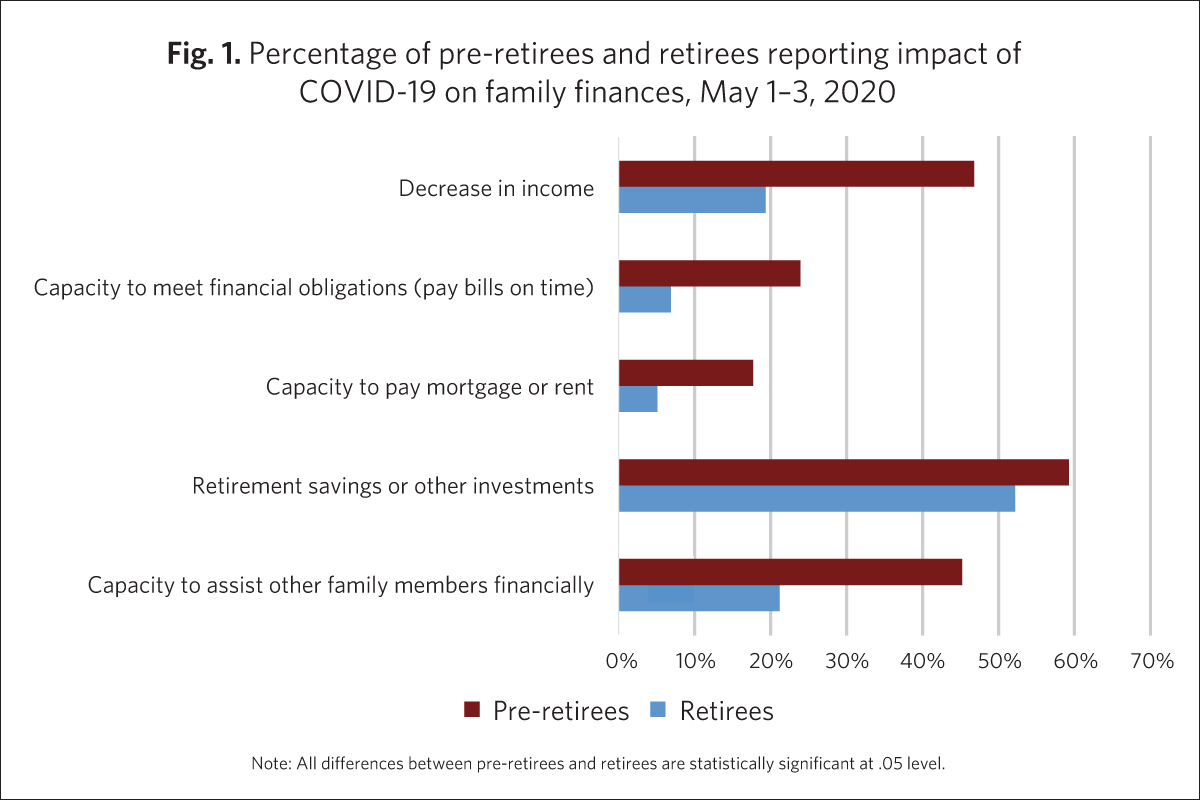

A survey conducted by the Leger, ACS and the Vanier Institute in early May provided one of the first glimpses into the pandemic’s financial impact on retirees.8 It showed that only 1 in 5 retirees9 reported a decrease in income as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, compared with close to one half of pre-retirees (47%) (fig. 1).

In fact, the polling data showed that some (7%) of retirees reported difficulty in their capacity to meet financial obligations, such as paying bills, compared with close to 1 in 4 pre-retirees (24%). Similarly, 1 in 20 (5%) retirees reported difficulty in paying mortgage or rent, compared with close to 1 in 5 pre-retirees (18%).

While retirees have access to public income support, many also have access to additional income support through savings or other investments. (In 2015, 50% of seniors in Canada reported receiving income from investments.)10 The COVID-19 outbreak resulted in financial market uncertainties and turbulences that added considerable stress on investors in general, and this is the area where retirees were most adversely affected. The polling data showed that more than half (52%) of retirees reported negative impact on their retirement savings or other investments – though the impact was greater among pre-retirees (59%).

Retirees assisting other family members financially

Family can be viewed as a potential source of insurance against abrupt financial shocks. Since some retirees were less exposed to the pandemic-related economic shocks, they have been a potential source of financial support for their children or younger family members, who may have been more adversely affected. A study on the impact of severe economic recessions found that, during the 2008 financial crisis, 28% of households in the United States reported getting financial help from family and friends.11

How did COVID-19 affect retirees’ ability to assist other family members in Canada? When asked, about 1 in 5 retirees (21%) reported that the pandemic had affected their ability to assist other family members financially. Among the pre-retirees, who were more exposed to the economic shock produced by COVID-19, the rate was 45%. Retirees who received income assistance from their children or grandchildren (some of whom could be pre-retirees) may therefore have also been indirectly affected in this way.

Retirement timing is being affected for one-third of surveyed Canadians

As families continue to navigate the impacts of COVID-19, data show that many workers are adapting their retirement plans. A recent US survey found that 39% of American workers are changing their retirement timing,12 primarily for financial reasons (e.g. they had to use some of their savings, some of their investments may have lost value during the pandemic, there is less certainty in general about how much money they will need in retirement).

A separate survey from Canada suggests a similar trend may be taking place in Canada, with one-third (33%) of adults who plan to retire saying that they will retire later than planned as a result of COVID-19.13 However, 8% of respondents said they would retire earlier than originally planned, possibly due to wanting to avoid continued uncertainty and turbulence in the labour market (if they are financially able to do so).

While it is too early to draw a clear picture of the diverse ways COVID-19 has impacted retirement in Canada, early data shows that retirees are less financially impacted on average, as pre-retirees seem to have been more exposed to the economic impacts. Nonetheless, surveys show that the increased uncertainty is having an impact on people’s retirement planning, and further research will be important to understanding how this is affecting family finances and well-being more generally.

Edward Ng, PhD, Vanier Institute on secondment from Statistics Canada

Notes

- Statistics Canada, “Labour Force Survey, May 2020,” The Daily (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2020). According to the Labour Force Survey, from February to April of 2020, 5.5 million Canadian workers were affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown, which included a drop in employment of 3 million and a COVID-19-related increase in absences from work of 2.5 million. Link: https://bit.ly/3j99UfM.

- Ana Fostik and Jennifer Kaddatz, “Family Finances and Mental Health During the COVID‑19 Pandemic” (May 26, 2020).

- See Ana Fostik, “Uncertainty and Postponement: Pandemic Impact on Fertility in Canada,” The Vanier Institute of the Family (June 30, 2020).

- Myriam Hazel, “Reasons for Working at 60 and Beyond,” Labour Statistics at a Glance, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 71-222-X (December 14, 2018). Link: https://bit.ly/2SJqjxW.

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, Canadians and their Money: Key Findings from the 2019 Canadian Financial Capability Survey (November 2019). Link: https://bit.ly/34ypopw.

- RBC, 2017 RBC Financial Independence in Retirement Poll (February 14, 2017). Link: https://bit.ly/2Yyyxe6.

- Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, “Prime Minister Announces Additional Support for Canadian Seniors,” Government of Canada (May 12, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/308AUp2.

- The survey, conducted by the Vanier Institute of the Family, the Association for Canadian Studies and Leger on May 1–3, 2020, included approximately 1,500 individuals aged 18 and older, interviewed using computer-assisted web-interviewing technology in a web-based survey. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to gender, age, mother tongue, region, education level and presence of children in the household in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (web panel in this case). However, for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,512 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.52%, 19 times out of 20.

- Retirees are defined as those aged 45 and above who reported being retired in the polling survey, when asked about their current occupation. Pre-retirees are other respondents in the same age group who reported an occupation other than homemaker or a student. Since there is no mandatory retirement age in Canada, among those aged 45 and more, the polling data showed that some 4% of those aged 65 and above were still working, while some 29% of the retirees in the same age group were in fact younger than 65.

- Statistics Canada, “Income Sources and Taxes (16), Income Statistics (4) in Constant (2015) Dollars, Age (9), Sex (3) and Year (2) for the Population Aged 15 Years and Over in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data and 2016 Census – 100% Data,” Data Tables, 2016 Census (September 12, 2017). Link: http://bit.ly/2i6MVUR.

- National Research Council, “Assessing the Impact of Severe Economic Recession on the Elderly: Summary of a Workshop” (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011). Link: https://bit.ly/2X8b9mU.

- Edward Jones Canada, The Four Pillars of the New Retirement (June 25, 2020).

- Ibid.

Report: COVID-19 and Parenting in Canada

September 3, 2020

In June 2020, the Vanier Institute prepared the report Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada for the UN Expert Group Meeting Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. Now available in English and French, this report highlights family experiences, connections and well-being during COVID-19, as well as the current resources, policies, programs and initiatives in place to support families and family life.

Families “Safe at Home” details federal, provincial and territorial resources created to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families. In addition to government responses, a summary is provided of the diverse range of available services that support families from pre-parenthood to adolescence and that serve parents across Canada, including those who belong to Indigenous, 2SITLGBQ+ and newcomer communities.

The Expert Group Meeting was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA), where experts from diverse fields from around the world connected virtually to discuss COVID-19 impacts, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Families “Safe at Home”: The COVID-19 Pandemic and Parenting in Canada

Nora Spinks, Sara MacNaull, Jennifer Kaddatz

Toward the end of 2019, news began to spread around the world about the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Like many other countries, Canada was facing the possibility of weeks and months with families living in isolation in their homes, changes to school and work schedules, and unknown impacts on family connections and well-being.

In 2020, global citizens around the world are living in and adapting to new ways of life while remaining “safe at home” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadians have been striving to respect physical and social distancing guidelines implemented by our governments and based on the recommendations of public health officials since March 10, 2020. For many families, the past three months have included parenting in close quarters with high levels of uncertainty and unpredictability while managing work commitments, fulfilling care responsibilities inside and outside the home, and homeschooling children of all ages. Despite the inability to plan and the unknowns about what the next few weeks and months might look like, most families are maintaining good physical and mental health, taking care of one another and weathering the storm with their neighbours and communities at a distance.

During these unprecedented times, the Vanier Institute of the Family has adjusted its focus to understanding families in Canada in a time of drastic social, economic and environmental change. The daily activities of individuals and families in Canada, what they are thinking, how they are feeling and what they are doing are all important factors to be addressed and understood in the short, medium or long term.

Accordingly, representatives from the Vanier Institute were co-founders of the COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, a multidisciplinary group of some of Canada’s leading experts along with some of their international colleagues. The network has identified important issues, key indicators and relevant socio-demographics to generate evidence-based responses addressing the social and economic dimensions of the COVID-19 crisis in Canada. As well, to understand the experiences of families during the pandemic, the Vanier Institute has internally mobilized knowledge from other available sources, including quantitative data from both government and non-governmental agencies, such as Statistics Canada and UNICEF Canada, as well as qualitative information from individuals, families and organizations across the nation. Analyses of these findings illuminate characteristics of family life both before and during the pandemic, providing insight into what Canadians fear and what they look forward to after public health measures are lifted.

Consistent with its core principles, the Vanier Institute honours and respects the perspectives of diverse families by applying a family lens and Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+), whenever possible.1 By examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and any of its associated “costs and consequences,” including fertility patterns, parenting, family relationships, family dynamics and family well-being, the Institute mobilizes knowledge to those who study, serve and support families to make sound evidence-based decisions when designing and implementing policies and programs for all families in Canada.

COVID-19 Pandemic Experience in Canada

As of May 31, 2020, 1.6 million people have been tested for COVID-19 in Canada (approximately 4.5% of the total population). Among them, 5% have tested positive for the virus, with 8% resulting in death.2 Seniors in long-term care facilities who have died of COVID-19 represent approximately 82% of all deaths linked to the virus.3

Families are like all other “systems” during the pandemic – their strengths and weakness are magnified, amplified and intensified as relationships, interactions and behaviours adapt to changes in routine, habits and experiences. Family connections, family well-being and youth experiences have all been dramatically affected.

Family Connections

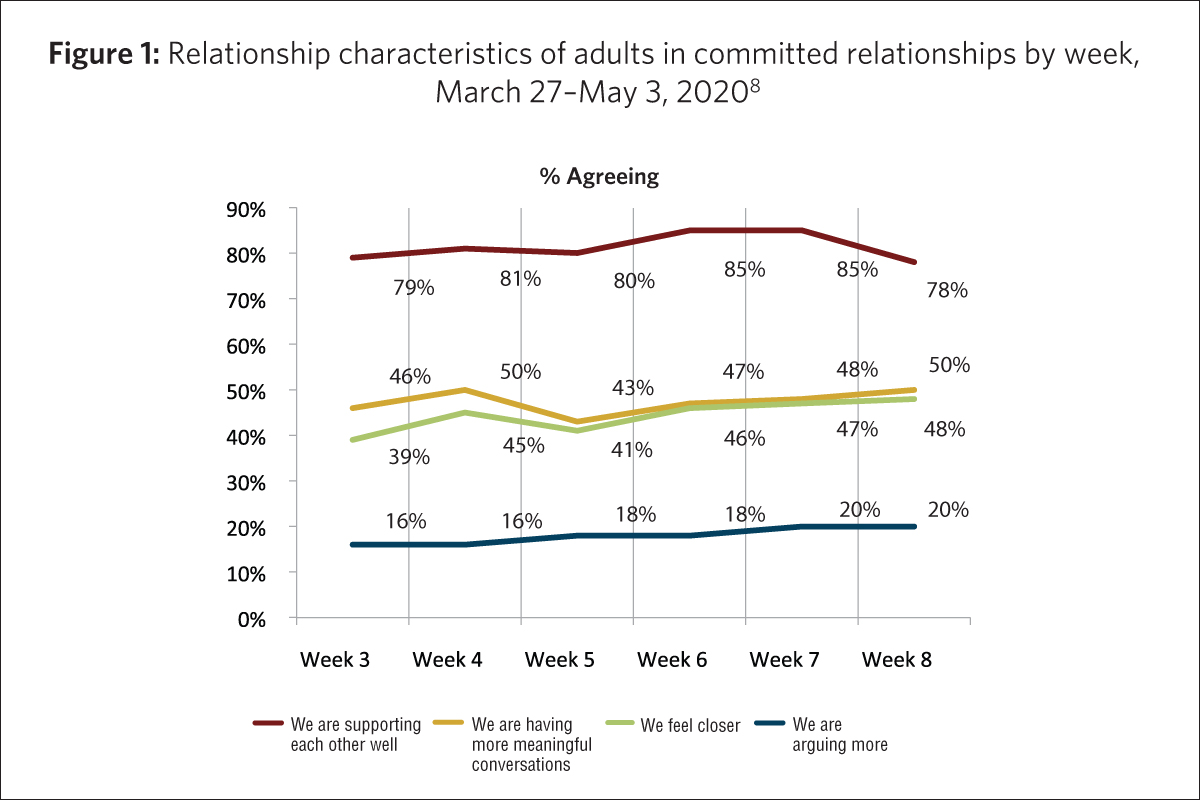

- Approximately 8 in 10 adults (aged 18 and older) who are married or living common-law agreed that they and their spouse were supporting one another well since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1). This figure varies only slightly for those with children or youth at home (77%) compared with those without children under the age of 18 in the household (82%).4

- Fewer than 2 in 10 adults in committed relationships said they had been arguing more since the start of the pandemic (Fig. 1).5

- Six in 10 parents reported they were talking to their children more often than before the lockdown began.6

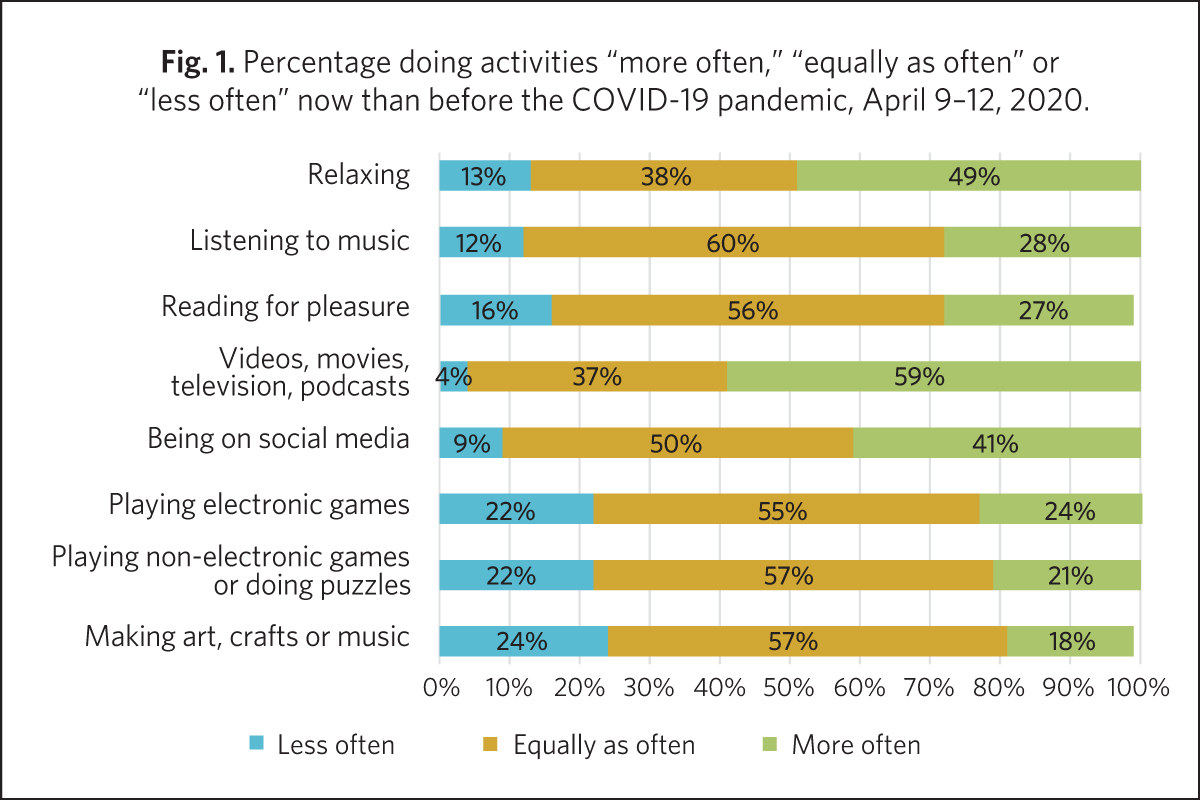

- When young kids were in the house, adults were almost twice as likely as those with no children or youth at home to have increased their time spent making art, crafts or music.7

On the other hand…

- One-third of adults said that they were very or extremely concerned about family stress from confinement.9

- 10% of women and 6% of men were very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home.10, 11

- About 1 in 5 Canadians had senior relatives living in a nursing home or facility, with 92% of females and 78% of men being very or somewhat concerned for their health.12

Family Well-Being

- More than three-quarters of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants reported either very good or excellent (46%) or good (31%) mental health during pandemic, in a survey conducted April 24–May 11, 2020.13

- Nearly half (48%) of Statistics Canada’s crowdsource participants said that their mental health was “about the same,” “somewhat better” or “much better” than it had been prior to the start of the pandemic.14

- About half of adults said they felt anxious or nervous or felt sad “very often” or “often” since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis.15

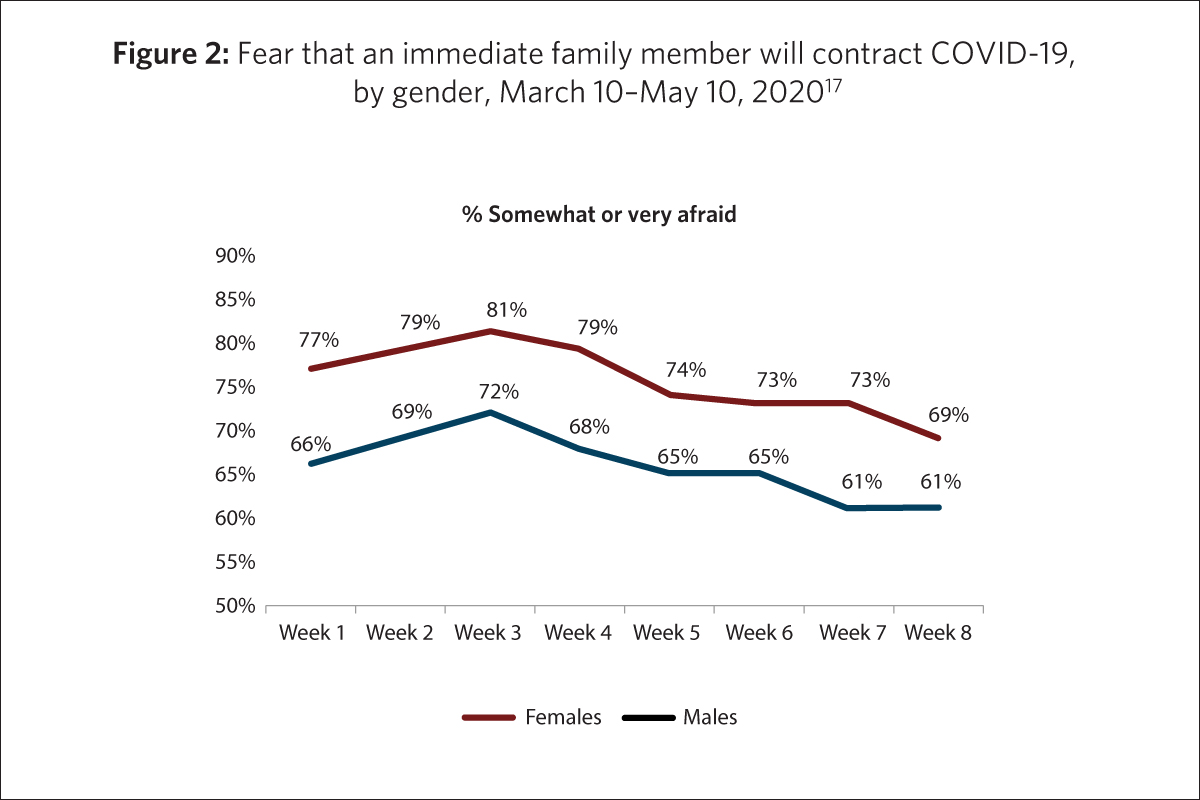

- Regardless of age group or week surveyed, women expressed being more afraid than men that they would contract the virus or that someone in their immediate family would contract it (Fig. 2).16

- Canadians were more afraid of a loved one contracting COVID-19 than they were of contracting it themselves. Adults who were “very” or “extremely”concerned about:

- their own health: 36%

- health of someone in household: 54%

- health of vulnerable people: 79%

- overloading the health care system: 84%18, 19

- More than 4 in 10 of adults living with children under the age of 18 in their home said they “very often” or “often” have had difficulty sleeping since the beginning of the pandemic.20

- When asked to describe how they have been primarily feeling in recent weeks, Canadians were most likely to say they were worried (44%), anxious (41%) and bored (30%); fully one-third (34%) also said they were “grateful.”21

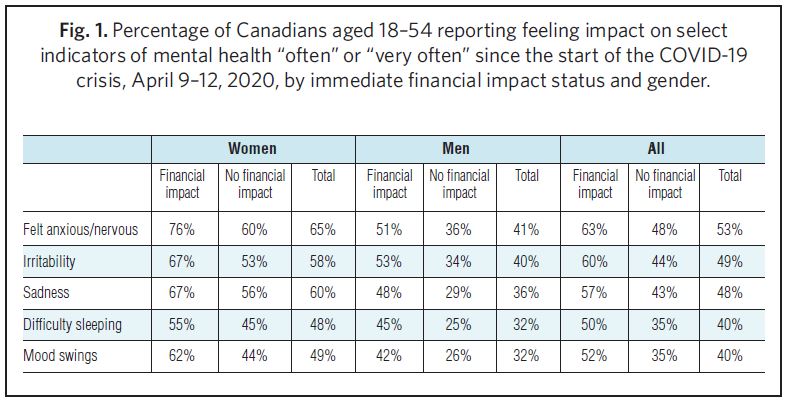

- Women were considerably more likely than men to report experiencing anxiety or nervousness, sadness, irritability or difficulty sleeping during the pandemic.22

- Adults across all age groups continued to exercise during the pandemic, as two-thirds of adults aged 18–34 reported that they were exercising equally as often or more often during the pandemic than they were before it started. The figures were similar for adults aged 35–54 (62%) and aged 55 and older (65%).23

- Younger adults (aged 15–49) were more likely to report an increase in junk food consumption than older adults.24

- Food banks saw a 20% average increase in demand, with some local food banks, such as those in Toronto, Ontario, seeing increases as high as 50%.25

- More than 9 in 10 people aged 15 and older said that the pandemic had not changed their consumption of tobacco nor cannabis.26 Just under 8 in 10 reported that the pandemic had not affected their drinking habits.27

Youth Experiences

- Youth aged 12–19 said they got most of their information about COVID-19 and public health measures from their parents.28

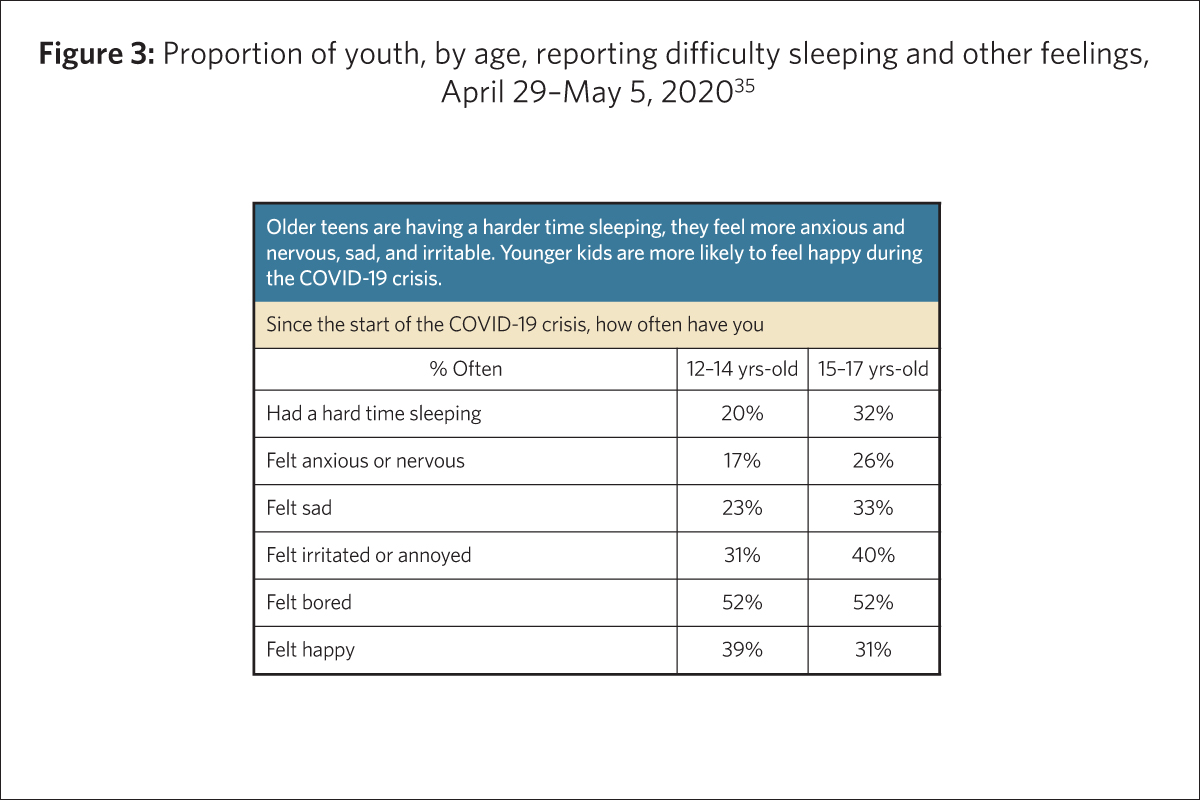

- Older youth, aged 15–17, were more anxious than younger youth, aged 12–14.29

- Among youth aged 15–17, 50% reported that the pandemic had had “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their mental health, compared with 34% of youth aged 12–14. Approximately 4 in 10 youth aged 12–17 reported “a lot” or “some” negative impact on their physical health.30

- Approximately half of children and youth across all age groups missed their friends the most while in isolation.31

- Though 75% of youth claimed to be keeping up with school while in isolation, many were also unmotivated (60%) and disliked the arrangement (57%) (i.e. online learning; virtual classrooms).32

- Many youth said they were doing more housework or chores during the pandemic.33

- Older teens (aged 15–17) were having more difficult sleeping, feeling more anxious or nervous, sad and irritable. Younger teens (aged 12–14) were more likely to feel happy than older teens (Fig. 3).34

COVID-19 Pandemic Response in Canada

Since March 2020, the provincial, territorial and federal governments have announced diverse benefits, credits, programs, initiatives and funds to support families across Canada. The purpose of these recent resources is to offset, mitigate or alleviate the financial impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on families during this period of uncertainty, including the following:

Temporary Increase to the Canada Child Benefit (CCB)

The Canada Child Benefit (CCB) is a tax-free monthly payment made to eligible families to help with the cost of raising children under the age of 18. The amount of the benefit varies depending on the number of children, the age of the children, marital status and family net income from the previous year’s tax return. The CCB may include the child disability benefit and any related provincial and territorial programs.36

For families already receiving the CCB, an additional $300 per child was added to the benefit in May 2020. For example, a family with two children received $600, in addition to their regular monthly CCB payment, which could be up to a maximum of $553.25 per month per child under the age of 6 and $466.83 per month per child aged 6–17.37, 38

Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB)

In April 2020, Canada’s federal government established the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to support workers impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The CERB provides $2,000 every four weeks to workers who have lost their income as a result of the pandemic. Eligibility includes adults who have lost their job or who are sick, quarantined or taking care of someone who is sick with COVID-19. It applies to wage earners, contract workers and self-employed individuals who are unable to work. The benefit also allows individuals to earn up to $1,000 per month while collecting CERB.39

As a result of school and child care closures across Canada, the CERB is available to working parents who must stay home without pay to care for their children until schools and child care can safely reopen and welcome back children of all ages.

As of early May 2020, more than 7 million Canadians had applied for CERB since its introduction.40

Mortgage Payment Deferral

Homeowners across Canada who are facing financial hardship due to lack of work or decreased income during the pandemic may be eligible for a mortgage payment deferral of up to six months.

The payment deferral is an agreement between individuals and their mortgage lender, which includes a suspension of all mortgage payment for a specified period of time.41

Special Good and Services Tax Credit

The Goods and Services Tax credit is a tax-free quarterly payment that helps individuals and families with low and modest incomes offset all or part of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) or the Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) that they pay.42

In April 2020, the federal government provided a one-time special payment in April 2020 to those receiving the Goods and Services Tax credit. The average additional benefit was nearly $400 for single individuals and close to $600 for couples.43

Temporary wage top-up for low-income essential workers

The federal government is providing $3 billion to increase the wages of low-income essential workers. Examples of essential workers (though variable by province or territory) may include health care professionals, long-term care facility employees and grocery store employees.

Each province or territory is responsible for determining which workers are eligible for this support and how much they will receive.44

Emergency Relief Support Fund for Parents of Children with Special Needs (Province of British Columbia)

To support parents of children with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of British Columbia created a new Emergency Relief Support Fund. The fund will provide a direct payment of $225 per month to eligible families from April to June 2020 (three months).

The payment may be used to purchase supports that help alleviate stress, such as meal preparation and grocery shopping assistance; homemaking services; caregiver relief support and/or counselling services, online or by phone.45

COVID-19 Income Support Program (Province of Prince Edward Island)

In April 2020, the Government of Prince Edward Island announced financial support for individuals whose income has been impacted as a direct result of the public health state of emergency, as well as additional protocols to keep residents safe.

The COVID-19 Income Support Program will help individuals bridge the gap between their loss of income and Employment Insurance (EI) benefits or the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) by providing a one-time, taxable payment of $750.46

Support for Families Initiative (Province of Ontario)

In April 2020, the Government of Ontario announced direct financial support to parents while Ontario schools and child care centres remain closed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new Support for Families initiative offers a one-time payment of $200 per child aged 0–12 and $250 for those aged 0–21 with special needs.47

Emergency Allowance for Income Assistance Clients (Northwest Territories)

For Income Assistance clients registered in March 2020, the Government of the Northwest Territories provided a one-time emergency allowance to help with a 14-day supply of food and cleaning products as the stores have them available.

The Income Assistance (IA) program is designed for residents who are aged 19 and older and who have a need greater than their income. The emergency allowance received by individuals was $500 and for families it was $1,000.48

Parenting in Canada: Government Priorities, Policies, Programs and Resources

The Government of Canada and the provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments provide support to parents in Canada in myriad ways. In addition to the supports provided to assist families during the COVID-19 pandemic, as described in the previous section, a selection of current priorities, policies, programs and resources that are current and existed pre-pandemic are highlighted below.

Early Learning and Child Care

Early learning and child care needs across Canada are vast and diverse. The Government of Canada is investing in early learning and child care to ensure children get the best start in life. As a first step, the federal, provincial and territorial Ministers responsible for early learning and child care have agreed to a Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care Framework. The new Framework sets the foundation for governments to work toward a shared long-term vision where all children across Canada can experience the enriching environment of quality early learning and child care. The guiding principles of the Framework are to increase quality, accessibility, affordability, flexibility and inclusivity. A distinct Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework was co-developed with Indigenous partners, reflecting the unique cultures and needs of First Nation, Inuit and Métis children across Canada.49, 50

Before- and After-school Care

Canada’s federal government priorities currently include working with the provinces and territories to invest in the creation of up to 250,000 additional before- and after-school spaces for children under the age of 10, at least 10% of which would allow for care during extended hours. Priorities also include decreasing child care fees for before- and after-school programs by 10%.51

Just for You – Parents

“Just for You – Parents” is a federally created web-based list of resources for parents on topics, including alcohol, smoking and drugs; child abuse; childhood diseases and illnesses; educational resources; family issues; healthy living; mental health; parenting tips (childhood development); school health; and work–life balance. Each topic includes a range of subtopics that direct parents through links to the most up-to-date information available in Canada on issues of importance to them and their children.52

Guaranteed Paid Family Leave Program

In 2019, the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development was tasked to work with the Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion to improve and integrate the existing Employment Insurance-based system of maternity and parental benefits and work with the province of Quebec on the effective integration with its own parental benefits system.53

- Maternity and Parental Benefits Administered through the Employment Insurance (EI) program in Canada (excluding Quebec), maternity and parental benefits include financial support (i.e. income replacement for eligible workers) to new mothers and parents following the birth or adoption of a child. The number of weeks and amount paid to each parent varies depending on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the government).54 In Quebec, the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) administers the maternity, paternity, parental and adoption benefits. The amount received by parents is also dependent on the type of benefit, number of weeks and maximum amount payable (as determined by the provincial government). In 2019, the average weekly standard parental benefit rate in Canada reached $464.00 per month.55, 56

Modernizing Canada’s Federal Family Laws

On June 21, 2019, Royal Assent was given to amend Canada’s federal family laws related to divorce, parenting and enforcement of family obligations. The first update to family laws in more than 20 years, this initiative will make federal family laws more responsive to the needs of families through changes to the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act, and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act. The majority of the amendments to the Divorce Act will come into force July 1, 2020, while amendments to the other Acts will take place over two years. The legislation has four key objectives: promote the best interests of the child; address family violence; help to reduce child poverty; and make Canada’s family justice system more accessible and efficient.57

Provincial and Territorial Child Protection Legislation and Policy

The federal, provincial and territorial governments of Canada recognize the importance of surveillance in providing evidence about the contexts, risk factors and types of child maltreatment to inform policy, program, service and awareness interventions. Through their child welfare ministries, the provincial and territorial governments are responsible for assisting children in need of protection; they are also the primary source of administrative data and information related to reported child maltreatment. Preventing and addressing child maltreatment is a complex undertaking that involves the engagement of governments at all levels and in various sectors, including social services, policing, justice and health. At the federal level, the Family Violence Initiative brings together multiple departments to prevent and address family violence, including child maltreatment. The Department of Justice is responsible for the Criminal Code, which includes several forms of child abuse. As the Criminal Code currently stands – which has been debated by advocates and parents alike – section 43 legally allows for the use of corporal punishment on children by select individuals as long as does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstances.58, 59

Nobody’s Perfect

Introduced nationally in 1987 and currently owned by the Public Health Agency of Canada, Nobody’s Perfect is a facilitated parenting program for parents of children aged 0–5. The program is designed to meet the needs of parents who are young, single, or socially or geographically isolated, or who have low income or limited formal education, and is offered in communities by facilitators to help support parents and young children. It provides parents of young children with a safe place to build on their parenting skills, an opportunity to learn new skills and concepts, and a place to interact with other parents who have children the same age.60

Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities

The Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) Program is a national community-based early intervention program funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada. AHSUNC focuses on early childhood development for First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and their families living off-reserve. Since 1995, AHSUNC has provided funding to Indigenous community-based organizations to develop and deliver programs that promote the healthy development of Indigenous preschool children. It supports the spiritual, emotional, intellectual and physical development of Indigenous children, while supporting their parents and guardians as their primary teachers.61

Parenting in Canada: Pre-Parenthood to Adolescence62

For expectant parents (or those considering parenthood), the months leading up to the birth or adoption of a child can be exciting and overwhelming. There are many things to prepare for – including the unexpected – in advance of the little one’s arrival. Support in Canada often includes regular and free visits with an obstetrician-gynecologist, a midwife or other registered health care professionals to ensure healthy growth and development. Programs and services are also available in communities across Canada to prepare and plan for parenthood.

- 2SITLGBQ+ Family Planning Weekend Intensive This two-day program is structured to explore pathways to parenthood and strategies for achieving one’s vision of kinship and family. Participants are encouraged to ask questions, gather information and build community, while exploring topics such as co-parenting, multi-parent and single parent families, pregnancy, kinship struggles and self-advocacy. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

- Preparing for Parenthood Geared toward parents-to-be, this program offers information about how to remain healthy during pregnancy and what to expect during the early days and weeks of parenthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Mommies & Mamas 2B/Daddies & Papas 2B This 12-week course is geared toward gay/lesbian, bisexual and queer men/women who are considering parenthood. The course includes resources and discussions to explore practical, emotional, social, ethical, financial, medical, legal, political and intersectional issues related to becoming a parent. Topics explored include co-parenting, surrogacy, parenting arrangements, non-biological and adoptive parenting, fertility awareness, pre-natal care options and legal issues. (LGBTQ+ Parenting Network)

Newborns and Infants

Caring for a newborn or infant comes with many triumphs and challenges. For parents, programs and services are offered across the country, many free of charge, including visits with pediatricians and registered health care professionals. Postnatal care services vary across regions and communities, which may include informational supports, home visits from a public health nurse or a lay home visitor, or telephone-based support (e.g. Telehealth) from a public health nurse or midwife.63 Organizations across the country also offer drop-in programs for parents, grandparents and caregivers to support healthy child development and attachment.

- Roots of Empathy At the heart of the program are an infant and parent who visit a local classroom every three weeks over the course of the school year. Along with a trained Roots of Empathy Instructor, students observe the baby’s development and feelings. This program provides opportunities for parents and infants to take part in teaching emotional literacy and empathy to children aged 5–12, while strengthening their own bonds to each other. (Roots of Empathy)

- Parenting My Baby Tailored to new parents to provide opportunities to learn, participate in discussions on various topics related to infancy, child development and parenting, as well as opportunities to meet fellow new parents. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Bellies & Babies This drop-in group is geared toward pregnant women and new parents with babies from birth to one year. The group provides individual and peer support for pregnant women and postnatal mothers and provides resources and support to new parents. Resources include topics such as the importance of early secure attachment, nutrition, breastfeeding, mental health, infant development and parenting. (Sunshine Coast Community Services Society)

- Young Parents Connect This informal support group is geared toward parents and parents-to-be under the age of 26. It provides an opportunity to meet other young parents, ask questions and share concerns. Each session also includes a fun, interactive activity for children and parents together. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

Toddlers and Preschoolers

Programs for toddlers and preschoolers include a variety of activities to engage both children and their parents to support healthy child development and parent–child attachment. Programs may include drop-in activities, such as those offered by the Boys and Girls Club of Canada or through municipal recreation centres. The drop-in program – offering dancing, story time, arts and crafts and much more – provides opportunities for parents, caregivers and grandparents to take part in learning activities to create, explore and play. Drop-ins welcome moms, dads, grandparents and caregivers, while also providing opportunities to meet and connect with others within the community.

- Parenting Skills 0–5 This online parenting class is designed for families experiencing challenges, providing parents with a foundational understanding to raise their children during the first five years. Topics in this class include child development and personality, discipline, sleep and nutrition. Parenting skills classes are also available for parents with children aged 5–13 and 13–18. (BC Council for Families)

- Fathering Tailored to fathers, including new dads, those experiencing separation or divorce, teen dads and Indigenous dads, this series of resources provides information on how to navigate the various stages of childhood while providing practical tips in support of both fathers and their children. (BC Council for Families)

- Dad HERO (Helping Everyone Realize Opportunities) This project consists of an 8-week parenting course (offered in select correctional institutions in Canada) and a Dad Group both inside the facility for incarcerated fathers and in the community for fathers who were previously incarcerated. This project was designed to educate and teach fathers about parenting, child development and growth, and their role in their children’s lives. Dad HERO provides parenting education and support connecting fathers with their children and improve their mental health and well-being. (Canadian Families and Corrections Network)

School-Aged Children

As children begin and progress through the formal education system in Canada, they encounter various people (i.e. peers, educators) and influences (i.e. social media). Programs and services for parents of school-aged children provide practical tips, informative resources and opportunities to meet and engage with fellow parents in their communities.

- Parenting School-Age and Adult Children This resource was created to support newcomer parenting programs and address some of the challenges that newcomer parents and caregivers may have with parenting in Canadian society. The goal of the program is to gain effective communication skills, better understand the Canadian school systems and create a safe space for parents and caregivers to address their questions and concerns relating to children integrating into the wider Canadian society and culture. (CMAS)

- Positive Discipline in Everyday Parenting This workshop series promotes non-violent discipline and respects the child as a learner. It is an approach to teaching that helps children succeed, gives them information and supports their growth from infancy to adulthood. (EarlyON Child and Family Centres)

- Newcomer Parent Resource Series Available in 16 languages (e.g. Urdu, Arabic and Russian), this resource series explores various topics of interest tailored to meet the unique needs of immigrant and refugee parents of young children. Topics include Keeping Your Home Language, Guiding Your Child’s Behaviour, Helping Your Child Cope with Stress, Children Learn Through Play, and Listening to and Talking with Your Child. (CMAS)

- Parenting after Separation: Meeting the Challenges This six-week program is geared toward parents who have recently experienced separation from their partner. Parents meet once a week to discuss the challenge associated with parental separation and divorce and learn practical strategies to support their children. (Family Service Toronto)

- Foster Parent Support This program provides direct, outreach-oriented support to foster parents/caregivers and the children/youth in their care. Support workers work directly with the family in their home, in the community or via phone. This program is intended to be flexible in meeting the unique needs of each foster family and can offer a variety of supports, including teaching conflict resolution skills, de-escalation techniques, collaborative problem solving and using strength-based and trauma-informed approaches. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

Adolescents

Parenting a teen can be challenge, especially in the rapidly evolving era of technology. Adolescence can also be a difficult time for teens who may be questioning their identity, their purpose and envisioning their goals for the future. Programs for parents of teens recognize the importance of supporting children through adolescence as they transition into adulthood.

- Parents Together This is an ongoing professionally facilitated education and group support program for parents who are experiencing challenges while parenting a teen. This program helps parents address their feelings (e.g. guilty, isolation) and provides opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge that can help decrease conflict in the home between parents and their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Transceptance This is an ongoing monthly peer support group for parents and caregivers of transgender youth and young adults. The support provides support and education, reduces isolation and stress, and shares information, including strategies for dealing or coping with disclosures. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

- Parenting in the Know This 10-week education and support program to learn more about adolescent development, teen mental health and other common issues that parents experience. Local guest speakers, community resources, practical ideas and connections with others experiencing similar issues help parents feel better equipped to parent their teen. (Boys and Girls Club of Canada)

- Families in TRANSition (FIT) This 10-week program is geared toward parents/caregivers of trans- and gender-questioning youth (aged 13–21) who have recently learned of their child’s gender identity. The program provides support to parents/caregivers to gain tools and knowledge to help improve communication and strengthen their relationship with their youth; learn about social, legal and physical transition options; strengthen skills for managing strong emotions; explore societal/cultural/religious beliefs that impact trans youth and their families; build skills to support their youth and family when facing discrimination, transphobia and/or transmisogyny; and promote youth mental health and resilience. (Central Toronto Youth Services)

Looking Ahead

Families are the most adaptive institution in the world. They are resilient, diverse and strong.

As countries around the world begin to focus on the post-pandemic future, families and family experiences will continue to evolve and adapt. Parents may return to work outside the home, when children return to school and child care, and many will continue to work remotely. Some extracurricular activities will return, while classes like martial arts may continue to be delivered online.

While predicting the future has never been easy, the impact and realities of the global pandemic on families is not yet known, and programs and services may require adjustments in order to support the physical, mental, emotional and social well-being of parents and their children through a trauma-informed lens. Though many families may have been safe at home, some experienced an increase in violence, stress, isolation and anxiety.

Policy and program development, benefits, resources, supports and services will require a comprehensive understanding of families in Canada, their experiences and aspirations; thoughts and fears; and hopes and dreams during this period in time which has evolved and may forecast what lies ahead. The research and innovation behind the many initiatives, including those included in this paper, will help guide evidence-informed decisions; the development, design and implementation of evidence-based programs, policies and practices; and evidence-inspired innovation at all levels of government, community organizations, workplaces and faith communities to ensure families in Canada thrive now and into the future.

Nora Spinks is CEO at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Sara MacNaull is Program Director at the Vanier Institute ofthe Family.

Jennifer Kaddatz is a senior analyst at the Vanier Institute of the Family.

Published on June 23, 2020

______________________________________________________________________________

This report was originally published on June 23, 2020 on the UN Department of Economic and Social affairs (UN DESA) website as part of the Expert Group Meeting on Families in Development: Focus on Modalities for IYF+30, Parenting Education and the Impact of COVID-19. This event was organized by the Division for Inclusive Social Development (DISD) of UNDESA to convene diverse experts from around the world virtually to discuss the impact of COVID-19 on families, assess progress and emerging issues related to parenting and education, and plan for upcoming observances of the 30th anniversary of the International Year of the Family (IYF).

Appendix A: Organizational and Program Overview

Founded in 1977, the BC Council for Families (BCCF) has been developing and delivering family support resources and training programs to professionals across the province of British Columbia as a way to share knowledge and build community connections. The BCCF offers online classes, resources and programs to support parents and children from infancy to adulthood.

The Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada offer educational, recreational and skills development programs and services to children and youth in communities across Canada. The Clubs strive to provide safe, supportive places where children and youth can experience new opportunities, overcome barriers, build positive relationships and develop confidence and skills for life. Many Clubs also offer programs and services to parents to support child development and attachment.

__________

Founded in 1992, Canadian Families and Corrections Network (CFCN) aims to build stronger and safer communities by assisting families affected by criminal behaviour, incarceration and reintegration. Their work includes developing resources for children, parents and families to understand the correctional system and process in Canada and to support families as they manage the experience of having a loved one incarcerated.

__________

The Central Toronto Youth Services (CTYS) is a community-based, accredited Children’s Mental Health Centre that serves many of Toronto’s most vulnerable youth. Their programs and services meet a diversity of needs and challenges that young people experience, such as serious mental health issues; conflicts with the law; coping with anger, depression, anxiety, marginalization or rejection; and issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.

__________

Founded in 2000, CMAS focuses on caring for immigrant and refugee children by sharing their expertise with immigrant serving organizations and other organizations in the child care field. They currently identify gaps in service and work to create solutions; establish and measure the standards of care; and support services for newcomer families through resources, training and consultations.

__________

EarlyON Child and Family Centres provide opportunities for children from birth to age 6 to participate in play and inquiry-based programs, and support parents and caregivers in their roles. The goal of the EarlyON is to enhance the quality and consistency of child and family programs across Ontario.

__________

For more than 100 years, Family Service Toronto has been supporting individuals and families through counselling, community development, advocacy and public education programs. This includes direct service work of intervention and prevention such as counselling, peer support and education; knowledge building and exchanging activities; and system-level work, including social action, advocacy, community building and working with partners to strengthen the sector.

__________

Founded in 2001 and housed at the Sherbourne Health Centre (in Toronto, Ontario), the LGBTQ+ Parenting Network supports lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer parenting through resource development, training and community organizing. The Network coordinates a wide range of programs and activities with and on behalf of LGBTQ parents, prospective parents and their families, including newsletters, print resources, support groups, social events, research projects, advocacy and training.

__________

For more than 30 years, Roots of Empathy has strived to build caring, peaceful and civil societies through the development of empathy in children and adults. The goals of Roots of Empathy are to foster the development of empathy; develop emotional literacy; reduce levels of bullying, aggression and violence; promote children’s pro-social behaviours; increase knowledge of human development, learning and infant safety; and prepare students for responsible citizenship and responsive parenting.

__________

Since 1974, Sunshine Coast Community Services Society (SCCSS) has provided services for individuals and families along the Sunshine Coast (British Columbia). Programs are focused around child and family counselling; child development and youth services; community action and engagement; domestic violence; and housing.

Notes

- GBA+ is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ also considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability. Link: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/index-en.html

- Government of Canada. “Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update” (May 31, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html

- Marc Montgomery, “COVID-19 Deaths: Calls for Government to Take Control of Long Term Care Homes,” Radio-Canada International (May 25, 2020). Link: https://www.rcinet.ca/en/2020/05/25/covid-19-deaths-calls-for-government-to-take-control-of-long-term-care-homes/

- A survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted weekly starting in March (beginning March 10–12), through April and May 2020, included approximately 1,500 individuals aged 18 and older, interviewed using computer-assisted web-interviewing technology in a web-based survey. Some weekly surveys included booster samples of specific populations. Using data from the 2016 Census, results were weighted according to gender, age, mother tongue, region, education level and presence of children in the household in order to ensure a representative sample of the population. No margin of error can be associated with a non-probability sample (web panel in this case). However, for comparative purposes, a probability sample of 1,512 respondents would have a margin of error of ±2.52%, 19 times out of 20.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19,” The Daily (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200408/dq200408c-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Though data varies, reports have claimed that consultations by the federal government reveal a 20% to 30% increase in violence rates in certain regions which is supported by organizations such as Vancouver’s Battered Women Support Services that has reported a 300% increase in calls related to family violence during the pandemic. Links: https://bit.ly/2OKYsK0, https://bit.ly/2ZOiF8f.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Statistics Canada. “Canadians’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic” (May 27, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200527/dq200527b-eng.htm

- Ibid.

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada’s healthcare system is publicly funded, which means that all Canadian residents have reasonable access to medically necessary hospital and physician services without paying out-of-pocket. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-health-care-system.html

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Worry, Gratitude & Boredom: As COVID‑19 Affects Mental, Financial Health, Who Fares Better; Who Is Worse?” (April 27, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-mental-health/

- Survey by Leger, the Association for Canadian Studies and the Vanier Institute of the Family.

- Ibid.

- Statistics Canada, “Canadian Perspectives Survey Series 1: Impacts of COVID-19.”

- Beatrice Britneff, “Food Banks’ Demand Surges Amid COVID-19. Now They Worry About Long-Term Pressures,” Global News (April 15, 2020). Link: https://bit.ly/3boEHRe.

- On October 17, 2018, the use of cannabis for recreation and medicinal purposes among adults became legal in Canada. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/cannabis/

- Michelle Rotermann, “Canadians Who Report Lower Self-Perceived Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic More Likely to Report Increased Use of Cannabis, Alcohol and Tobacco,” StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada (May 7, 2020). Link: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00008-eng.htm.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, in partnership with Experiences Canada and the Vanier Institute of the Family, conducted a nation-wide COVID-19 web survey of the 12- to 17-year-old population in Canada from April 29 to May 5. A total of 1191 responses were received, and the probabilistic margin of error was ±3%. Link: https://acs-aec.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Youth-Survey-Highlights-May-21-2020.pdf

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Angus Reid Institute. “Kids & COVID-19: Canadian Children Are Done with School from Home, Fear Falling Behind, and Miss Their Friends” (May 11, 2020). Link: http://angusreid.org/covid19-kids-opening-schools/

- Ibid.

- The Association for Canadian Studies’ COVID-19 Social Impacts Network.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada Revenue Agency. “Canada Child Benefit” (April 8, 2020). Link: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview.html