April 3, 2018

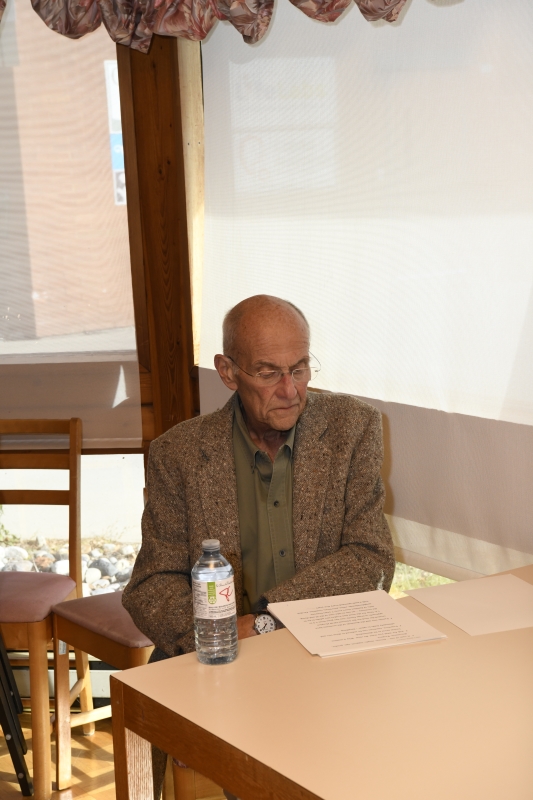

Alan Mirabelli: Hub Hospice and the Palliative Care Experience

Alan Mirabelli was the Vanier Institute of the Family’s Executive Director of Administration, who retired in 2007 after more than 30 years of service. He was diagnosed with cancer the first time in 2015 and again in 2017. Throughout his treatment and following his terminal diagnosis, he continued to be of service, mentoring many emerging artists and seasoned photographers, community leaders and elected officials. His characteristic kindness, generosity and mentorship had a significant impact on many people across Canada and abroad.

Over the years, Alan gave countless presentations, keynote addresses and lectures, and he facilitated many workshops with diverse groups in hotel ballrooms, quaint retreats and boardrooms and conference rooms. His final presentation was hosted by Hub Hospice Palliative Care, a unique community-based hospice-at-home organization in Almonte, Ontario that Alan came to know, as a recipient of their caring and compassionate services. He spoke to a large audience of community members, academics, health care professionals, end-of-life service providers/volunteers and their families. You could hear a pin drop as people clung to his wise and perceptive words. Alan invited people to donate to Hub Hospice, and died only weeks after giving the presentation.

This article is based on Alan’s presentation, which has been edited for print.

Hello, how are you?

In the Maasai culture, the common greeting is quite different – and it leads to a different result. Their greeting is, “How are the children? Are the children well?” By paying close attention to greetings, you can learn a lot about what matters to a people. When you consider the Maasai greeting, there’s a vision in the culture that goes beyond today. It’s not just a casual, passing remark – it reflects a sense of care and a sense of direction for the culture’s future.

When you live in a culture in which you are truly vulnerable, where there aren’t systems of health care and they don’t have all the things we take for granted, this expression of care is from the heart. The answer they expect is that all of the children are doing well, not just some of the children.

I use that story to point out the difference in cultures where care is expressed daily, and people aren’t simply asking if the children are well. What they’re doing, in fact, is preparing the next generation to look after them when they’re old. It’s anticipating the needs; if you don’t acculturate the young people and society to be interdependent and of service, you might not have access to the things you need in your times of vulnerability.

I think it’s very appropriate to what I want to tell you today, because it’s why Almonte has become my home since 1981. I have felt the daily care and concern for the future. It’s different in Almonte. It’s developed in a manner that’s consistent with what I see in the Maasai and the question of the greeting.

This presentation was prepared by me at 3:00 a.m. this morning. There is a reason for that. Some of you know me personally, and you know what an incredibly positive journey I have been on since being diagnosed with cancer.

I have been filtering things so that they become meaningful to somebody else, to other people who have not had this experience themselves. From these notes, which are only eight pages, triple-spaced, I could talk for 10 hours about this community of Almonte and about the people who have supported me thus far and will continue to do so until the end.

On a personal note, if you hear a negative undertone anywhere in this presentation, it is an accident of a mind. It is because it is becoming fogged. This afternoon is really tough for me mentally. If you hear any negativity, discount it. My heart is 100% positive and enlivened by the emotions, which are felt with joy and gratitude.

“If you don’t acculturate the young people and society to be interdependent and of service, you get none of the things you require and need in your times of vulnerability.”

Now I was asked to introduce myself, and rightly so, because anything I’ve done professionally – the fact that I was doing A, B, C in the past, giving hundreds of speeches per year – doesn’t help here. This is the toughest one.

What makes this conversation – and it is a conversation – is that I’d really like you to interrupt and ask a question when it is appropriate for you to ask that question. It is the equivalent of you saying, “Are the children well?” This matters to me. I want to understand you.

What makes this a unique case? Well, it is a case of one, me. You can diagnose this old guy on your own. I am a single person. Most people who turn to hospice turn because spouses and family members need the support as they go through the process of watching somebody they care about die.

By the way, you will not hear, as much as I can help it, euphemisms come out of my mouth. You will not hear of someone “passing” here. You die – that’s it. Euphemisms keep us from focusing on what really matters; and we have a culture that will talk at length about children and how much goes into that end of life, but we never want to talk about the other side.

I knew this day was coming since March 11, 1948. I didn’t know how and when I would die, I just knew that one day I would. There it is.

The second reason I’d like to talk about this is I’ve had the luxury of time – and it is a luxury. To be told you have cancer and you have four to six months (now down to one), it gives me time to say thank you, and to not do all of the things that my head says I have to. It is lovely to see my lawyer here, because she took care of the logistics around death and dying in the first week after I received the terminal diagnosis. Now I can speak from the heart, which is the only thing that matters to me. It really is.

As I said, I’m a case of one. I’m a single person, and I’m male. Usually there are people who surround you during times of illness, such as a spouse, who provides support and helps arrange for care. I’m very clear about how I want to leave this earth. I needed to find the people who would help me get there in the manner that I chose, not in the manner in which they wished to impose upon me. Therein lies a very nice bridge in this community.

I knew Hub Hospice existed, but I had a completely false image of what it was. I thought it was bricks and mortar, and they parked me in there, and I’d live my last days there. It’s a far more intelligent system than that, for which I am grateful. It is just what I need. I want a chance to express my gratitude, to be able to say “Thank you.” I want a chance to encourage the development of this model of care further in ways that really are meaningful not only to me, but to the family I choose to define for myself.

The other thing that this journey has taught me is that with the help of the volunteers that I have – and I have unbelievable volunteers, they’re really friends on call; that’s the way I can describe them – the experience that you get, through no other way than by doing what they do, is not an intellectual exercise but very much an emotional one. From my point of view, because I’ve had the luxury of time and I have a very clear vision of how I want to leave, I could ask for what I wanted clearly.

“Euphemisms [about death] keep us from focusing on what really matters, and we have a culture that will talk about children and how much goes into the beginning of life, but we never want to talk about the other end of life.”

Choosing Love and Life

Now I want to talk about why that matters. Just because I’ve been diagnosed with terminal cancer doesn’t mean that I choose to stop living! I wanted to find volunteers who, if asked, would help me live – fully – not watch me die and hold my hand while I do it. That time will come, but that is not what I want right now. As some of you know, art and photography is a lifeline for me. It is a meditation. It is everything that feeds my soul. I wanted two people who, if I said, “Could you drive me somewhere,” would say, “What time?” And they both have.

If I need to go downtown because I want to get something from the store, even though I’m weakening, “What time and when?” You know, just getting that opportunity to nourish that little piece of me has done more to enliven me. These days are getting harder and harder, but both of the volunteers are interested in what I’m doing, so the conversations become real and not sort of passing time.

When I was clear in asking for what I wanted, they were able to respond in a manner that works for them and works for me, and I tell you, it is what keeps me going every day. Every day is a surprise and they’re part of it somehow. Whether it is anticipating the next visit, arranging the next visit or outlining what we might do – and it might have to change on that day because I’m not up to it – that possibility is so vital to me.

Life can be just two emotions: fear and love. The moment I got the diagnosis, I chose the latter. It could be morbid. Ultimately for me, choosing that was probably the wisest thing I could do because it led to an increased sense of spirit. The number of people who have texted me and emailed me and said, “You’re showing courage doing that.” I said, “There’s no courage involved. It is what I want.” It is who I am. Why should I change that?

Let me switch tracks for a minute. Some of you know that I used to work for the Vanier Institute of the Family as Co-Director with Bob Glossop: an incredible 30-year history. I thought a number of things had changed over those years, but either we haven’t perceived them or if we did perceive them, we have chosen to ignore them at our peril.

We’re making assumptions at the level of public policy when it comes to care, possibly at local policy, in the service sector, about who is home to look after people – anybody – and provide the care they need. If you think about families becoming smaller and the demands of the economy, a need has been created for community groups like Hub Hospice. This evolution in our families and communities wasn’t sudden.

These are changes that are continuing. The first institution in society that reacts to change is never government, it is never our public institutions – it is always family. If you can’t make ends meet at the end of the month, you do one thing and one thing only, you send another member of the family out to work. How many double-income families do we have here? A lot of them. Who is home to provide care? Grandparents now are active, and they are not necessarily available to provide care.

Finally, families in the 1940s had on average five people in the household, but this has since fallen to three and it continues to fall. For many single people, there’s really nobody available to provide care.

If you look at mobility rates (how often people move), 50% of Canadians move every five years between cities, actually between streets, cities, provinces, countries. Try that with a bush and see how long it survives. When there is no one, who do you call when you’re told you’re terminally ill? Who?

Well, my family is no different. I have one sister who lives five hours away and one son who has five children under 11 years of age. So the question is, how do I arrange for the things that I know I would need, when I know I want them in a particular manner so that I don’t become a victim of cancer?

In my case, I learned about Hub Hospice services that were available in in my community by accident. That’s why I offered to make this presentation: to help others learn about the exemplary services available. I heard about the hospice service and how it works; I chose to reach out and make contact because, for me, it was an element of hope.

“Life can be summed up in two emotions: fear and love. The moment I got the diagnosis, I chose the latter.”

Getting the News: “It’s Terminal”

I am going to stop here for a moment and describe what it was like to get the news that you have a terminal illness.

In April 2015, I was diagnosed with throat cancer. The oncologists in the medical system in general were superbly amazing. Everyone I met through my treatment showed me care and compassion.

The compassion part is what I was looking for. I don’t expect it from the medical system, as well organized as it is. This isn’t a blame game; there are simply too many patients, too many sick people, too many fears. There’s got to be some middle ground to transition to the human side. Then when you try to invoke it from the medical system, of course, you get their impatience, and I understand it. However, when you really need the health care system, it really comes through for you and there’s nothing better.

I was standing in the Mill Street Bookstore, talking to Mary (the store owner) when my cellphone rang. It was my family physician, who had received the radiology report. He asked if I could talk. It is not very often that you get a doctor calling you directly, and also hard to get them back on the phone, so I said yes as I stood in front of Mary. He told me that my cancer had metastasized and was terminal.

Mary knew something was serious, and she looked at my face with care and compassion. That look kept me grounded. Without knowing the details, she understood that something real and important had happened, so right there – in the community – that first moment of human connection made a difference that day and has ever since.

I thanked my doctor and I was taken aback for no more than 30 seconds – literally. It didn’t take any longer than that. It was: This is it… this is the road I am now on.

The metaphor I have used to describe this journey is my life being a run-on sentence. I do what I do, and I don’t give it much thought, because it is who I am. Then suddenly I got that call and it was like somebody put a comma in that sentence. That’s what I felt. In seeing that comma – which was my diagnosis – I was at a point of choice: What am I going to do after the comma and before the period? The choice took a nanosecond. It was that clear.

I then walked out the door and ran into a friend whom I knew through photography. He said, “You look a little white.” I said, “Well, I just got this news…” My fear of cancer just washed away. That point of choice was vital for me. For somebody else, it might take longer. But here was my concern, which had nothing to do with dying, end of life or my physical well-being: This will be a huge strain on my family. How do I manage that?That was my first reaction.

My second concern was that our health care system, as good as it is, has become so complicated. I had no idea where to start. I needed a navigator from the point of view of the system. I knew I needed help. But what I also knew was, and in my state, I’m a very emotional man by nature. I have no fears of expressing it. You’ll see me cry somewhere along the way. I’m very comfortable with that. But I was also concerned about where I would get the emotional support I needed without overtaxing the people in my life… my small, busy family… the people who care about me… the people who will be caring for me? Yet I knew that, if I was going to get through this with the joy and the sense of purpose that I have, I would need a circle of support around me.

“My life has been a run-on sentence… Then suddenly I got that call and somebody put a comma in that sentence… What am I going to do after the comma and before the period?”

What that led to was a question of how one prepares for death long before one faces it. I lived with depression throughout my adult life. Medication wasn’t the solution for me. So instead I took a year-long sabbatical and focused on developing a spiritual approach to my life, a life that you see in my photographs. My photographs are based on the beauty I see and the joy it brings to me. I share my images so they bring joy to others. It is a short way of saying how I have lived the last 20 years. I’ve chosen to live with daily meditations, focusing on meaning, creating meaningful relationships or receiving meaning by mentoring a sincere group of photographers who have given me purpose and joy in my life.

Jamming on the Brakes

I will give you some advice: don’t get involved in the love/fear debate, but develop an attitude and a set of actions that really do invite you in and provide clarity of what matters. My life was moving forward like everyone else’s, at considerable speed, when with that phone call from my doctor, it was like somebody had jammed on the brakes: the whole world continued to move forward, and I was right there at the windshield, stopped. It felt like I was pressed against this windshield and that I was alone. It is the aloneness that got me, and the burden that I’d become on others.

I can’t describe the aloneness because it is not loneliness. It is a wholeness that haunts. You want to say something to somebody because they mattered and yet you haven’t got the voice. You haven’t got the capacity to articulate something that is life-giving. It is a very strange feeling. Then I started to think, What if I were married? All of everything I’ve encountered as the patient has been absolutely superb. Absolutely superb! If I need something, I can probably figure it out. I can see if I can find somebody who can point me in the right direction.

I thought for that moment, at the windshield, that what I’m feeling has got to be better than what a spouse or family member is feeling, watching their relationship of a lifetime just fade into the haze in front of their eyes. Feeling that aloneness and that incapacity to make a significant difference beyond a certain point, I just couldn’t imagine.

Hub Hospice in Almonte: Authentic Kindness

When I first learned about Hub Hospice in Almonte and its unique approach to hospice at home, I thought, Somebody really thought this through. They understood the experience of the family caregiver; they started there in the family and the home. They understood the patient, but they also understood the spouse.

When I first learned about Hub Hospice in Almonte and its unique approach to hospice at home, I thought, Somebody really thought this through. They understood the experience of the family caregiver; they started there in the family and the home. They understood the patient, but they also understood the spouse.

I cannot imagine the conversations around the boardroom table that developed the vision that created this unique hospice model. Having negotiated many a vision and tried to implement them, they can be a nightmare! There are competing interests, there are competing visions, there are the big bricks-and-mortar people, there are the little keep-it-simple people… there is a wide range. It is a palette. To find one that actually feels right and to fulfill it, I just thought, Wow.

What is unique about Hub Hospice is its focus on family. First of all, it started from the position of the spouse. Second, whatever arguments, and I’m sure they weren’t pleasant, that derived from this model, delivered so consistently… the compromise is elegant. I can’t say it any other way. There is a volunteer perspective that I now have come to respect and give that is based on kindness. It is authentic. It is a kindness that provides a very human foundation for what I’m going through and what I imagine a spouse would be going through.

I have two volunteers. Each has a personal style. What amazes me is how complementary they are. Let me describe to you a meeting that I convened in my home a few months ago. I brought my care team together to plan and prepare for my end-of-life journey and the living I want to do along the way. My team included my palliative care nurse (a hero in my books); my son; my power of attorney for personal care, who is the person who ultimately makes all of the decisions for me when I can’t; and my Hub Hospice volunteers. I sat at the head of my dining room table, and I felt like I was the chairman of my destiny because of who was present. When I got emotional – and I did because there was such kindness at that table – whenever an issue arose, the appropriate person had a contribution to make. The team had only respect for me and my wishes. That’s when the tears started.

To have a team, who didn’t know each other before the meeting, set aside the things that usually divide a group and focus on developing the care plan – and occasionally have a hand reach out and just hold mine with no words – that comes from this notion that we start from: kindness.

There were no competing interests; I trusted everything that was communicated. I had confidence that the journey would be as I wanted it to be, and everyone around the table agreed to work together to see that it did. That they could work so coherently together so quickly speaks volumes to everyone in the room. The way they treated my son, trying to hear and elicit his concerns, that was probably the most touching moment for me. In terms of how hospice acted, they were mandated to support me and my family in this manner.

“There is a volunteer perspective that I now have come to respect and give that is based on kindness. It is authentic.”

My biggest joy was when I first met with the staff person and, subsequently, my volunteers. One of the first questions in the interview that I asked with the volunteers and my staff person was who they would talk to and who they wouldn’t talk to. The response I got just made my heart burst, because they understood completely the modernity of life. Family is like an elastic band: it stretches, it contracts, depending on the economy, the culture and a variety of other things. For many now, particularly the young, they create their own tribe or family. They really do, and I have as well.

I can’t tell you how appreciative I am of the flexibility that allows me to define who is intimate, equal to a blood tie, because some blood ties are very messy.

I have assurance that the right people are looking out for me when I define who is “family” and who needs to be provided with the information. To have an organization willing to do that, it is what I want now – and that is what they provide. I have alluded to the fact that, for me, palliative care is not about death and dying: it’s about finding a group that will support life and living.

The Importance of Listening

I’ve just told you how much family means to me in terms of not just being limited by blood. Why? Because that’s how we form lasting relationships in this culture at this time. I certainly have. The reason I cherish the people who are part of the hospice, and I mean cherish, is because when I talk to them, first of all, they listen. They have probably the most acutely developed sense of being rather than doing. It is a rare commodity. Everybody shows up on my door wanting to do something.

What amazes me is that each Hub Hospice volunteer whom I have dealt with is perceptive enough to recognize that, and to make the space to be quiet when it’s necessary, to laugh when it’s important and to cry when it matters. When I say palliative care is what supports life and living, the people at Hub Hospice do it. When I ask for a perspective, a point of view because of their experience, I get clear responses to consider.

“Palliative care is not about death and dying: it’s about finding a group that will support life and living.”

I don’t get told what to do, I don’t get told how to do it. To have a palette – and some of it I refer to as my emotional guides, some of it I refer to as a topographical map that helps me navigate my day and the care I receive because I have no idea how to manage it all… I have never done this before! – to have people who have experience and the human side of attentiveness is what I cherish every day.

“Defining end of life care is… to make the space to be quiet when it’s necessary, to laugh when it’s important and to cry when it matters.”

Now I am going to change to another part of this: the palliative part of it that I’ve come to understand, unfortunately. You notice when you’re around young families who want to talk about education or you’re around young teachers who want to talk about education, they never talk about learning. They talk about money and unions and the board of education, but not learning.

It is the same when you try to form an organization of any kind. You define your end, but then you get a hundred reasons why you can’t do it. Maybe it’s that you don’t have enough money, that you have to go through this step, that step.

A Different Model of Palliative Care

The way Hub Hospice is modelled is brilliant. There is nothing that can’t be done because they’re not depending on grants or bricks and mortar – they are dependent on volunteers, who work to ensure that I’m where I want to be.

Where do I want to be? In my home with the things I adore, with the things that make me alive. To be removed from my home to go to a “hospice” or “day program” in the cold or extreme heat would be uncomfortable. But these wise people have adopted a system that is flexible, responsive and allows me to stay at home. What I’ve come to appreciate is that Hub Hospice has a model that supports human needs. They’re based on kindness, not on the currency of efficiency.

Each cancer patient is complex and receives care from a well-developed medical model in our publicly funded health care system. From my experience, all the techs, all the doctors, all the nurses are fantastic, but it’s patient-focused. Hospice is all about support and guidance for the family – the family as defined by the patient.

For families, it is asking the right questions at the right time. When I need help, whom do I call? Will it be given freely? Will it be given begrudgingly or generously? Those are the things that matter. Support for those who care is vital, and palliative care supports dying with dignity and grace, peace and joy, and love and care. That’s it for me.

Palliative care speaks to and supports those who care for the patients and who ultimately ease the anxiety of the patients – the family. As I’ve told you, my life has been a run-on sentence – and then comes the comma, a terminal diagnosis. I’m moving toward the period and the end of my journey is coming. I’ve chosen a path and I’m choosing to speak about it. I’m not battling anything. I’ve chosen to live fully until I can no longer do so with or without support.

Making Images Is Like Palliative Care

When I make an image, and most of you will know and have seen my images, I always stand behind the camera and the tripod for 45 minutes or more before I make the image, because that time is an invitation. A slight shift from here to there or from this position to that position changes everything. The whole interpretation changes – the whole meaning changes – the whole experience changes. It is that focus, positioning and patience that is crucial.

Hub Hospice is like the photographer in me. The organization and the volunteers stand there observing, waiting for 45 minutes or more to see if they need to make a slight adjustment in order to make a big difference for the patient and their family. I can’t think of a better metaphor, because, in my experience, it’s the small gestures that make the biggest difference.

“Palliative care speaks to and supports those who care for the patients and who ultimately ease the anxiety of the patients – the family.”

In this day and age, it is very hard to find volunteers who will do anything more than once – forget about doing something more than once, twice, three times over a month. To get somebody to commit for an indefinite period of time to care for someone is challenging, and for someone they don’t know seems impossible. Making that commitment is heroic on the part of the volunteer and speaks volumes about the organization. Volunteers don’t make their commitment alone; I find it incredible that there are families in this community that will support the volunteers to sacrifice a good part of their lives for an extended and indefinite period of time. That is a demonstration of how the community supports one another directly and indirectly, a fact I don’t take for granted for a minute. It is to be celebrated and to be honoured.

It leads to a more potent question: how did Almonte develop this kind of caring and compassionate culture? These things don’t happen by accident. I chose to live in Almonte in 1981 because it is a community I felt I wanted to live in. Partly because community matters to me and I really have a sense of what community means to me. I can honestly say Almonte is my home. Having lived in different countries, having lived in different cities, Almonte is my home. It is partly because of its scale, but also because of who chooses to live here, its history and its traditions.

This is what has made this experience so enlivening. It is not an accident, for me, that the hospice was therefore created as it was. First of all, you have a community that has a long history: where a lot of people didn’t move every five years, where families have deep roots, where those roots are visible and talked about. Stories are shared. When somebody like me comes in where families are scattered all over the world, I see them as kind of memories. Somebody mentions a name and somebody at the table will spend the next 20 minutes telling the family history. The fact that people here tell stories, stories about their history, their families for generations, that’s what it’s meant.

It’s not always cute, it’s not always nice and pleasant, but the roots are deep and they’re real. I, the city guy, don’t have to come in and do anything. I just have to absorb tradition. This is a traditionally rich area having large families. They are still in the area. They still talk to each other. They still make contributions. It is the stories we tell each other that remind us that we live in a community that has provided a solid foundation for places like Hub Hospice.

We have an incredibly well-educated community; the people who come from afar tend to want to stay. They’re here to absorb this tradition, understand it, feel it and see how modern culture can be fitted in so that Almonte keeps up but doesn’t lose its strength of tradition. That’s how I see the palliative care process having been formed. People at that table remembering how it used to be done, recognizing it can’t be done that way, but rather how it can be adapted within a legal framework and within compassionate frameworks. It has that think and feel. It is not make-believe. It is why I like what they’ve done with Hub Hospice.

“Almonte is my home. It is partly because of its scale, but also because of who chooses to live here, its history and its traditions.”

I may be making all of this up because this is a case of one, and you can’t generalize. But from a case of one, I’ll tell you it’s made a huge difference.

Today my state of mind may be very fogged, but my state of heart is clear as crystal. It really is. My state of emotions is high and comfortable. The emotions are about gratitude and appreciation for our community that is responsive and chooses to be caring and compassionate. I no longer worry. It has become a conversation that is evolving as it needs to, with comfort, dignity, respect, tenderness and I can’t think of enough words to express how it feels.

The decision I made to come here in 1981 is the best decision I ever made. The decision to say this is my home and to really believe it is the best decision I ever made. I can’t imagine going along this journey any other way but with the joy and gratitude that you’ve afforded me. To the board, to the staff, to the volunteers at Hub Hospice, I thank you. You’ve made the difference. Not just intellectually, but to the heart and to the soul.

I thank you for listening.

Download Alan Mirabelli: Hub Hospice and the Palliative Care Experience

Alan died on December 20, 2017, a few weeks after he gave this presentation at Hub Hospice Palliative Care. Along with family and friends, his Hub Hospice volunteers were with him as he took the last few steps on his journey. In his final days, every time he woke up he would say, “I am so lucky, I am so blessed, I am so grateful.”

Published on April 3, 2018 with permission from Alan’s family (Marilyn Mirabelli and Michel Mirabelli)

Photo (top of page) by Peter Waiser

Stay in the know

InfoVanier

A monthly newsletter of research, resources, and events

Linktree

Get alerts on new Vanier Institute publications, events, and announcements