Donna S. Lero, Ph.D.

In order to better understand families’ experiences and aspirations, it is crucial to understand the context in which families and their individual members live. Families are society’s most adaptable institution, constantly reacting to cultural, social and economic forces while affecting those same forces through their thoughts and behaviour. A number of recent and projected demographic and social trends are expected to have a significant impact on relationships between different generations, and exploring these shifting contexts can provide valuable insight into how intergenerational relations are affected and the potential impacts they have on social cohesion within families and in different generations – the question of intergenerational equity.

Population aging increases caregiving needs and lengthens intergenerational relationships

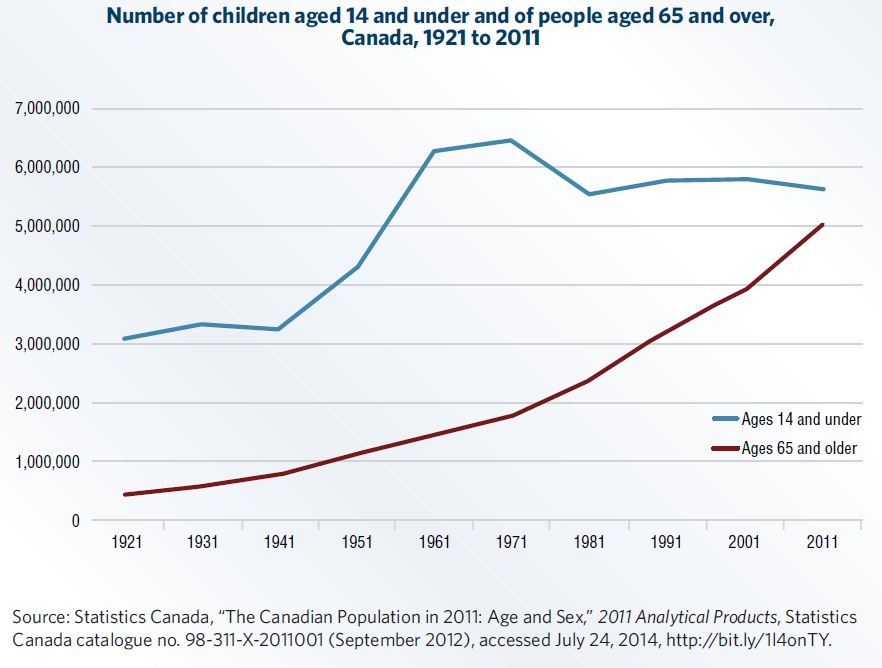

Population aging is a feature of most developed societies, a result of low fertility rates and people living longer. These two forces are transforming the traditional population pyramid to a more rectangular shape, shifting the size and proportion of older populations in society. In Canada, the proportion of the population 65 years and over increased from 8% in 1971 to 15.3% in 2013, and will be close to 25% in 2050.

Canada is not alone in this regard: across Europe, the proportion of the population aged 80 and over is expected to increase from 4% in 2010 to close to 10% by 2050, with substantially higher proportions in Germany, Italy, Japan and Korea. These trends have major implications for government planning in order to address pensions, health care costs, home and residential care, and supports for family caregivers.

Of increasing concern is the projection that there will be more individuals in their advanced years, with fewer children and grandchildren to provide care and assistance. Using census data, Janice Keefe and her colleagues have projected that the number of elderly people needing assistance in Canada will double in the next 30 years and that the decline in the availability of children will increase the need for home care and formal care, particularly over the longer term. Notably, it is projected that close to one in four elderly women may not have a surviving child by 2031.

Baby boomers continue to be the largest population group, still dominating the workforce, but starting to reach traditional retirement age. This group is experiencing caregiving pressures for aging parents and facing significant challenges managing paid work and care. In 2007, 37% of employed women and 29% of employed men aged 45–64 were caregivers, and those proportions are set to increase. At the same time, an estimated 28% of caregivers still have one or more children aged 18 or younger at home.

A recent trend in Canada and the U.S. is an increasing proportion of “older workers” typically defined as 55 years and older. Still healthy and capable, many people in their 60s and 70s are either prolonging careers or taking new jobs, often to supplement savings and/or limited pension income that will not last through their full retirement years. Canadian federal, provincial and territorial ministers responsible for seniors have identified the promotion of workplace supports for older workers, including supports to balance work and care, as one of two priority areas for the coming years.

In addition to being the largest population group, baby boomers have encountered different social circumstances growing up than their parents did. In the U.S. and Canada, they have been influenced by changes in women’s rights and roles, the sexual revolution, higher rates of divorce and enhanced educational opportunities. The longevity of the boomers’ relationships to their siblings and to aging parents has been described as “unprecedented” and their experiences as caregivers to their aging parents and their expectations and capacities as they age will significantly influence policy developments related to pensions, health care and long-term care.

Baby boomers have also had particularly close relationships with their children, and a poor economy that is limiting their young adult children’s opportunities and contributing to delayed family formation and careers is a source of significant concern. As a result, many boomers are concurrently providing substantial care to aging parents with chronic illnesses; have significant ties to siblings who, like themselves, may be carefully monitoring their retirement savings and possibly planning to extend their involvement in the labour force; and are providing support to their own children. Siblings, parents and grandparents today have a greater amount of time together than in previous generations. Vern Bengston has described this as a positive trend at the micro level, as it creates prolonged periods for shared experiences and opportunities for exchange that can strengthen intergenerational solidarity, despite a general societal trend at the macro level toward weakening norms governing intergenerational relations.

Greater diversity in family forms increases the role of “chosen families”

Baby boomers and their adult children have experienced higher rates of separation and divorce, remarriage, blended families and common-law arrangements than previous generations. An increase in same-sex unions and marriages is also evident. These complex and diverse relationships can result in what Karen Fingerman describes as “complex emotional, legal and financial demands” from former partners, estranged parents and relatives such as former in-laws or stepchildren. While complicating the nature of relationships and creating ambiguous expectations for exchange and support, Bengston suggests that the diverse network of relationships can provide a broader “latent kin network” (sometimes referred to as “fictive kin”) that can provide additional support when needed.

This latent kin network, which increasingly includes close friends who function “like family,” may substitute for or augment the support available from fewer or estranged family members, who may be geographically distant and/or have weaker ties over time. Interesting policy questions emerge when legal rights, financial benefits and other supports that were developed with heterosexual nuclear families in mind do not extend to the broader diversity and complexity of family forms evident in modern societies.

Longer transitions for youth into the labour market increases intergenerational dependency

A variety of cultural, social and economic conditions has been identified as factors that are contributing to a prolonged transition to adulthood in North America. Evidence of this lengthy and sometimes precarious transition to financial independence includes young adults’ extended involvement in education, a higher proportion living at home with their parents than previously, delayed and difficult entries into the job market and into long-term career paths, and delayed conjugal formation and child-bearing.

These processes have been occurring over a period of time, but are increasingly evident and in contrast to the experiences of previous generations at the same age. Young people’s experiences have led to longer periods of financial dependency on parents at the micro level and they are contributing to emerging concerns about intergenerational equity at a broader social level.

Given increasingly tight job prospects and the importance of education for good jobs in a knowledge-based economy, more young adults are turning to post-secondary education programs and the gaining of credentials as a way to increase employment opportunities and earnings. In Canada and other OECD countries, almost half of those in their early 20s are attending educational institutions full-time. Consequently, the tendency to stay in school longer, in conjunction with the extended time it takes to obtain employment in a related field, is increasing the average duration of the school-to-work transition.

Although post-secondary education adds human capital for individuals and for society, the benefits of a university degree may not be evident when graduates have difficulty finding suitable employment, as has been the case in recent years. Those with only a high school education face an even more difficult time finding a job that pays a living wage.

A complicating factor for many university graduates in Canada and the U.S. is the level of student debt. According to a 2013 Bank of Montreal student survey, current university students in Canada anticipate graduating with over $26,000 in debt. Student debt levels have escalated, particularly in the last decade, as tuition fees have increased – a function of limited government funding. Current student loan programs require that graduates begin repayment almost immediately after graduation. In addition to the anxiety accumulated debt produces for students, it is a substantial impediment to gaining financial independence from parents and it contributes to delaying marriage, child-bearing, home ownership and other purchases.

A serious concern, reflected in a growing number of current news reports, is the challenge young adults have finding jobs that afford a living wage. As described by James Côté and John Bynner, “Today’s young people face a labour market characterized by an increasing wage gap with older workers, earnings instability, more temporary and part-time jobs, lower-quality jobs with fewer benefits and more instability in employment.” These authors go on to state an additional concern: that “the decreased utility of youth labour in the context of this job competition has produced a growing age-based disparity of income (emphasis mine), contributing to increasingly prolonged and precarious transitions to financial independence.”

Statistics Canada has reported that, in 2011, 42.3% of young adults aged 20–29 lived in the parental home, either because they had never left it or because they returned home after living elsewhere. Most telling is the finding that, among 25- to 29-year-olds, one-quarter (25.2%) lived in their parental home in 2011, more than double the 11.3% observed in 1981.

The Pew Research Center’s report on the millennial generation in the U.S. (aged 18–33) has noted marked generational changes in the age of marriage. In 2013, just 26% of the millennial generation was married, compared to 48% of baby boomers (aged 50–64) when they were the same age. The current pattern of delayed child-bearing evident in Canada is a natural consequence. People are having fewer children (if any) and having them later. Beginning in 2005, fertility rates of mothers in their 30s has outnumbered the rates observed among mothers in their 20s. In 2011, 2.1% of all first-time mothers who gave birth that year were in their 40s, up from 0.5% in 1991.

Higher rates of immigration lead to greater diversity in intergenerational relationships

Rates of international immigration have increased dramatically in recent decades, spurred by greater opportunity to do so and economic needs. For many years, Canada has relied on international migration as a source of population and labour force growth. Resettlement policies and services aid in the transition of newcomers, promoting the learning of English or French, enhancing access to health and community services, and facilitating a smoother transition to the labour force.

Although newcomers may be more dependent on immediate family members for support, they experience wider discrepancies in expectations between generations in the family as a result of acculturation. For example, cultural and religious values may place particular emphasis on respect for elders and filial obligations to provide support, yet studies of immigrants from diverse backgrounds suggest that immigration and acculturation can place significant strains on newcomer families. This can particularly be the case when aging parents expect filial support and reject formal support and their adult children face economic challenges that require their involvement in precarious employment, multiple jobs or work that involves long hours or non-standard schedules.

In summary, multiple factors, including population aging, low fertility rates, increasing diversity in family forms, delayed transitions to financial independence and high rates of international immigration, affect the nature of intergenerational relations at both the micro and macro levels. As the population in Canada continues to age, generations will share relationships for longer periods of time. Longer intergenerational relationships mean that families (whether related by blood or marriage or “chosen” circles of kin) will have a greater amount of time in which members can provide support and care for each other, regardless of the context in which they live. Challenges include ensuring that supports are available that sustain caring relationships over time, especially in more complex circumstances and in a context of limited and fragmented supports for caregiving.

Dr. Donna S. Lero is a Professor in the Department of Family Relations and is the Jarislowsky Chair in Families and Work at the University of Guelph. She leads a program of research on public policies, workplace practices and community supports in the Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being, which she co-founded.

This article is an edited excerpt from Intergenerational Relations and Social Cohesion, a background paper prepared for the Regional Expert Group Panel Meeting marking the 20th anniversary of the International Year of the Family and first published in Transition magazine.